The trial in the case of Sergei KOVALYOV (CCEs 34-37) took place on 9-12 December in Vilnius, at the Supreme Court of the Lithuanian SSR.

[For Kovalyov’s arrest in December 1974, see CCE 34.1]

The chairman of the court was M. Ignotas, a member of the Supreme Court of the Lithuanian SSR. The people’s assessors were: Didsiuliene and Tereshin. The secretary was Saviniene. The public prosecutor was Bakucionis, a senior counsellor of justice and deputy-procurator of Lithuania.

At the beginning of the session a defence counsel was appointed by the court.

THE CHARGES

Sergei Adamovich KOVALYOV was charged under Article 70 of the RSFSR Criminal Code. He was accused of participation in the Action Group for the Defence of Human Rights and with having signed numerous statements and appeals written since 1969, including letters in defence of Grigorenko (1969), on the anniversary of the invasion of Czechoslovakia (1969), in defence of Bukovsky (1971), concerning Krasin and Yakir (1973), an appeal in connection with the deportation of Solzhenitsyn (1974), a letter to the UN concerning the Crimean Tatars (1974), a letter to the League for the Rights of Man concerning Bukovsky (1974), and others.

Kovalyov was also accused of having taken part in a press conference in A. D. Sakharov’s apartment on “Political Prisoner’s Day”, 30 October 1974 [CCE 33.8], and of transmitting abroad material on Soviet camps which was classified in the indictment as ‘defamatory information’.

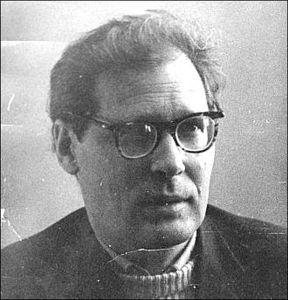

Sergei Kovalyov, 1930-2021

(December 1974 photo from investigation file)

Kovalyov was accused of restarting the publication of the Chronicle of Current Events, with collecting material for it, and with assembling, editing, and transmitting abroad CCE issues 28-34. The indictment made use of the similarity of the materials taken from Kovalyov when searched, to the contents of the Chronicle, and of marginal notes made by Kovalyov on certain documents. The charge of transmitting the Chronicle abroad was based on a statement made by Kovalyov jointly with Tatyana VELIKANOVA and Tatyana KHODOROVICH on 7 May 1974 [CCE 28.0], announcing their intention to aid the dissemination of the Chronicle and also because CCE issues 28-34 were being published by Khronika Press in New York.

Kovalyov was charged with possession of three issues of the Chronicle of the Lithuanian Catholic Church and with using their contents in the Chronicle of Current Events.

KOVLYOV was also accused of disseminating Solzhenitsyn’s book The Gulag Archipelago. A xerographic copy and part of a typewritten copy of the book were found at his apartment. The main evidence for this point of the indictment was the book taken from V. Maresin as he attempted to photograph it, and handed over to the KGB, and the letter from Kovalyov to Andropov (October 1974) demanding that he should return him his book.

Kovalyov pleaded not guilty to the charges presented to him in court. He refused to answer the question put to him by Judge Ignotas: “Do you admit the factual circumstances set out in the indictment?”

PETITIONS BY THE ACCUSED; CHOICE OF DEFENCE LAWYER

At the beginning of the hearing Kovalyov made three requests:

- To be given an opportunity to make use of the text of the [1948] Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

- To call a number of witnesses, including Leonid Krasin and Pyotr Yakir.

- To engage Sophia V. Kalistratova or Dina I. Kaminskaya as his defence lawyer.

Directly and through his wife, Kovalyov asked for these defence lawyers both during the pre-trial investigation and after its completion. Refusal to all requests was motivated by the defence lawyers lack of a ‘permit’ and other reasons.

In October 1975, Kovalyov’s wife Ludmila Boitsova sent a complaint to Terebilov, USSR Minister of Justice, regarding the unfounded refusal of the request to allow either Kalistratova or Kaminskaya to defend Kovalyov. A reply from the Moscow City Bar Association under the signature of Apraksin, the Chairman of the Bar Presidium, stated that the Bar acted independently to decide whether barristers might be sent to trials in other towns and cities.

The court dismissed all Kovalyov’s requests except for the calling of Krasin as a witness.

Kovalyov refused the defence counsel appointed by the court.

KOVALYOV TESTIFIES

The judge invited KOVALYOV To give evidence. The accused said he had not given evidence at the pre-trial investigation and had not participated in it, since he considered the proceedings illegal and criminal. As an exception to this stand, he had expressed his opinion about the way the evidence had been investigated.

It would be logical to adhere to this position in court as well, said Kovalyov, since people in such cases are being tried for their convictions, not for any crimes. Nevertheless he would take part in the trial in as far as the essential content of the case was concerned, i.e., whether there were false statements in the letters and in the Chronicle. He would not reply to questions as to who had signed one or another document, and where.

Setting out his attitude to the Chronicle and the letters, Kovalyov called them useful and not contrary to the law. He said that there were, unfortunately, some mistakes in the Chronicle of Current Events, and he agreed to take part in an analysis of the mistakes: he was in possession of evidence showing that these were genuine mistakes and not “deliberate falsehoods”.

THE WITNESSES

On the second day of the trial, 10 December, the questioning of witnesses took place. Twenty-two witnesses were called.

A doctor at the Dnepropetrovsk Special Psychiatric Hospital, L. A. Lyubarskaya, was questioned about the conditions in which Leonid Plyushch was kept and treated in the hospital. The judge put questions referring to material in CCE 34.9; Lyubarskaya replied invariably that everything in the hospital was done in accordance with the rules.

Kovalyov insistently supported the assertion that psychiatric hospitals in the Soviet Union are used for repressive purposes. He had been denied the possibility of defending himself, he stated, by not being allowed to call his own witnesses. The court refused Kovalyov’s request that Zhitnikova, the wife of Leonid Plyushch, should be called as a witness.

A. A. Kozhemyakina, deputy chief doctor at a psychiatric hospital in the Chekhov district of the Moscow Region, testified as a witness on the detention of Petro Grigorenko in the hospital. The judge dismissed a number of questions put to witnesses by Kovalyov. In particular there was no answer when Kovalyov asked: “Precisely how was an improvement in the health of Grigorenko manifested on his discharge?”

B. V. Polkin, a doctor at the central psychiatric hospital in the Kirov Region, and I. P. Kaftanyuk, a senior supervisor (warder) of the Internal Affairs Department in Kirov, were called to give evidence on an incident mentioned in CCE 32.12 (p. 54) regarding the detention of Yakov Khantsis in hospital and in Kirov Prison. The judge read out the testimony of Khantsis (from the record of the examination of his case) to the effect that during the period of his detention he was beaten and crippled, and when in prison he was put in the cooler seven times and was then put in solitary confinement. To this supervisor Kaftanyuk replied: “In Kirov Prison there are no one-man cells, and no one could physically endure the cooler seven times.” Asked by Kovalyov if he remembered any occasion when Khantsis showed violence, Kaftanyuk said: “Listen, I don’t have a head as big as the House of Soviets! I don’t remember.”

Several other incidents from the Chronicle were examined. Witness Gudas, a bulldozer operator at a forestry station in Kaunas district (CCE 32.10), and witness N. G. Skvortsova from Arkhangelsk (CCE 32.5) partially refuted certain points in the Chronicle. The judge disallowed many questions put by Kovalyov to the witnesses.

G. E. Korolyova, a witness from Moscow, testified that once when she called at the apartment of her relation, which she had rented to [Tatyana] Velikanova, she discovered there files containing letters from convicted persons. Since she regarded the contents of the files as suspicious she informed the police.

A group of witnesses were questioned in connection with an incident when Solzhenitsyn’s book, The Gulag Archipelago, was microfilmed. Three of the witnesses came from the Experimental Veterinary Institute: V. N. Chikina, senior technician; V. A. Gorbatov, head of a laboratory; and Yu. L. Dobrachev, head of the Fodder Section. A fourth witness V. M. Maresin, was a senior research associate at the Moscow Experimental Fish-Breeding Station. According to their evidence Gorbatov allowed Dobrachev to microfilm in the laboratory a book by [Albert] Schweitzer; Maresin helped Dobrachev, and when he had left, he began to microfilm The Gulag Archipelago. Summoned by Chikina, Gorbatov discovered this, removed the book and the film, and subsequently handed them to the KGB.

V. Maresin refused to say who owned the copy of The Gulag Archipelago being photographed; in so doing, he declared, he was guided by considerations of an entirely ethical nature.

V. F. Turchin, speaking as a witness, said that he had known Kovalyov well for a long time and considered that Kovalyov could not have engaged in the dissemination of any libellous documents.

After the questioning of the last witness, V. Turchin, Judge Ignotas, without any request from the witnesses, and having heard the opinion of the two parties — the agreement of the procurator Bakucionis to let the witnesses go and the objections of Kovalyov — said that all the witnesses were free to go and declared an intermission.

The witnesses Boitsova, Turchin, Litvinov, Yasinovskaya, Maresin and Mizyakin remained in their places. They were persistently requested to leave the hall, so that the building could be aired. The captain of the guard even referred to a resolution of the court.

ATTEMPT TO FORCE WITNESSES TO LEAVE COURTROOM

The witnesses expressed incomprehension. Why was permission to leave the court being interpreted as their obligation to do so, all the more so since such a resolution would be contrary to the Code of Criminal Procedure? The arguments of the witnesses made no impression. The intention was to remove the witnesses forcibly.

Then Turchin obtained an assurance from the captain that after the intermission they would be readmitted to the court. The witnesses left the court. A few minutes before the end of the intermission, the captain left the building of the Supreme Court. After the intermission not one of the witnesses except Ludmila Boitsova was re-admitted to the court. Guards in civilian clothing forcibly pushed them away from the doors, through ‘their own public’, which had begun to enter the hall; the ‘public’ unanimously expressed indignation at the “loutishness of the Muscovites”. M. M. Litvinov (a witness) and Yury Orlov, who also attempted to enter the hall, were taken to a special room and threatened with arrest “for resisting representatives of authority” (an hour later they were allowed to go).

Sergei Kovalyov, who, while being led from the courtroom, had noticed that many witnesses had not left their places, and who had heard the noise and disputation by the doors after the intermission, saw that only L. Boitsova of the witnesses was in the court and declared that he himself would not remain there unless all the witnesses were readmitted to the hall. He said that he did not intend to participate further in this “kangaroo court”, and that he was declaring a hunger strike until the witnesses and all those wishing to enter were admitted to the court. He demanded that he should be taken away. The judge declared an intermission until 10 a.m. on 11 December.

V. Turchin, V. Maresin, A. Mizyakin, M. M. Litvinov and F. P. Yasinovskaya wrote a statement addressed to the President of the Supreme Court of the Lithuanian SSR on the illegal exclusion of witnesses from the courtroom. They demanded the right to remain in the court until the end of the judicial examination, as indicated in Article 313 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Lithuanian SSR. All the witnesses received permission to be present in court.

*

On the morning of 11 December Kovalyov made a statement. He described the incident with the witnesses which had taken place on 10 December and put forward a number of demands:

“One, that provision be made for all witnesses who wish it to be present in court, and for me to be given the opportunity personally or through my wife and other witnesses to be convinced that some of them do not in fact wish to remain at the trial.

“Two, that the presence in court be assured of Andrei Dmitrievich SAKHAROV, Tatyana Mikhailovna VELIKANOVA, Alexander Pavlovich LAVUT, Malva Noyevna LANDA, Vitaly Alexandrovich REKUBRATSKY, Yury Fyodorovich ORLOV, and others of my friends who wish to be at my trial, and whom my wife and other witnesses will name. And on the same condition: I must have the opportunity of asking whether all who wish it have been admitted.

“Three, the court must examine a question which is not reflected in the materials of the case; as to whether the principle of the openness of court proceedings [glasnost] really is violated frequently and in an organized manner in the hearing of such cases. Among other things the court must question for this purpose, as witnesses, all the persons whom I have named and those who have come to my trial whom I do not know but whom the witnesses will name.

“Four, of course, I demand that this statement should be attached to my case. For my part I regret the expressions used by myself during today’s incident, which, although literary, were offensive. I am ready to apologize publicly before the court and the persons present in it and to express my thoughts in less strong language. I find that the following version is suitable:

“A limit must be put to your cynical arbitrariness. I shall not, and I do not wish to remain longer in a gathering of persons who deliberately violate the law or assist in this. Of course, I understand that an apology does not exclude the possibility of criminal responsibility for insulting behaviour. In the event that my moderate and not exaggerated demands are not met, I shall not end my hunger strike before the end of the judicial proceedings, and also, of course, I shall not return to the court.

“The court manages so easily without a defence counsel that it will of course easily be able to complete the case without a defendant either.

“I can only add the following: I shall be sad for an additional reason if my demands are not met. I was intending to present to the court weighty evidence of my innocence, while not in the least counting on a just verdict. And so, if I am deprived of this opportunity in the event that my demands are refused, I shall be sad. But what can one do?”

*

Judge Ignotas announced that the witnesses who had come today and asked to be admitted to the courtroom were present. Others had gone away to their places of residence. The question as to the presence in court of other persons was not a question of legal procedure and was left to the decision of the court commandant. The court resolved to reject the petitions of the defendant Kovalyov set out in his statement.

Kovalyov insisted that the principle of a public hearing was a procedural principle and references to the court commandant were unfounded. He demanded the satisfaction of all his demands or his immediate removal from the court. When the escort led him away, Kovalyov turned to the witnesses on the front bench and said: “My deep love to you all and to those who are outside the door and in Moscow! Warmest greetings to Andrei Dmitrievich [Sakharov]!”

After conferring together, the court ruled: to remove Kovalyov from the courtroom and to continue examination of the case in his absence.

*

The court proceeded to the examination of evidence. Consideration was given to the testimonials about S. A. Kovalyov from the places where he had been employed: [Moscow] University, where he worked until 1969, and the Moscow Experimental Fish-Breeding Station (1970-1974). The testimonials refer to the scientific results obtained by Kovalyov in “the field of electrophysiology and the modelling of continuous media” and the important practical results which he achieved.

The judge then listed the following documents:

- appeals and statements signed by Kovalyov,

- records of the examination of the case of Yakir and Krasin in which It was stated that Kovalyov, along with other persons, was a member of the Action Group:

- an Open Letter in which the aims and tasks of the Action Group are set out;

- an appeal to the 5th Congress of Psychiatrists in which it was stated that in our country medicine is used for repressive purposes;

- records of the examination of documents removed after a search, among them:

- various letters and materials from places of detention,

- material concerning arrests and court trials,

- lists of convicted persons,

- letters from camps,

- issues of the Chronicle of Current Events and the Chronicle of the Lithuanian Catholic Church,

- various materials concerning the state of affairs in the Orthodox Church of Georgia,

- the “Moscow Appeal” in connection with the exile of Solzhenitsyn,

- the text “We ask for the transmission of this information to international organizations which proclaim their aim to be the defence of personal freedom on the basis of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights”, and

- an appeal to the International Committee for the Defence of Human Rights, to the League for the Rights of Man and to Amnesty International.

Graphological examination showed that a number of the manuscript texts, and also notes on various typewritten documents, had been written by Kovalyov.

The prosecution (procurator) asked for certain other documents to be made public, which might have the significance of evidence, in particular, comparative tables of the similarity of materials which were removed from Kovalyov and citizen Korolyova to others which were published in the Chronicle.

By decision of the court Kovalyov’s requests for the summoning of witnesses were rejected and the evidence of Bochkovskaya, a doctor at a Dnepropetrovsk psychiatric hospital, given at the pre-trial investigation, was made public. In certain details this was at variance with the evidence given in court by Dr Lyubarskaya.

With this the judicial examination of the evidence was concluded and the court proceeded to hear the final pleas of both sides.

FINAL PLEAS

Sergei Kovalyov transmitted to the court a statement in which he said that he was prepared in all honesty to seek and discuss the form of his petitions, with all the necessary references to the law. but that he would not yield an inch in his demands. In his statement Kovalyov said:

“I regarded and still regard my participation in this trial as a matter of interest for myself, since I prepared thoroughly for it. I consider that I earlier behaved in an unsuitable manner: you yourselves provoked me by the removal of the witnesses. Without that I would not have put forward such demands. But the fact is that infringement of the law has now become so customary in judicial procedure in cases of this sort that a tendency has arisen to regard it as inevitable.

“I also would have accepted this tendency for the sake of a taking part in a real trial. However, it’s inappropriate now to regret the conflict which happened … I shall not alter my demands. I have not ceased my hunger strike nor shall I do so!”

The State prosecutor delivered his speech in the absence of the accused and any defence counsel.

The prosecution (procurator) again listed the letters and statements signed by S. A. Kovalyov, indicating Kovalyov’s authorship by the fact of the documents existence, their publication in an issue of the Chronicle or even by transcripts of the broadcasts of foreign radio stations — Radio Liberty, the BBC, the Voice of America. The subject matter of the documents was not analysed.

“A person’s convictions are a matter of indifference to the Soviet authorities” stated Prosecutor (procurator) Bakucionis: “provided that he keeps them to himself and does not commit criminal acts. In his arguments about freedom, in the documents which he (Kovalyov) signed, one thing shines through: an attempt to impose on Soviet people the bourgeois concept of freedom, the attempt to depict freedom as a person’s independence from society.”

The prosecutor spoke of the particularly great danger for our society of the activities in which Kovalyov had been engaged; he did not perceive any of the mitigating circumstances prescribed by the law and proposed that Kovalyov be sentenced to seven years in a strict-regime camp and an additional three years of exile.

The procurator drew attention to the behaviour in court of the witness Maresin in connection with his refusal to testify from whom he had received the book Gulag Archipelago.

After the procurator’s speech Judge Ignotas announced that the court would begin to confer in order to determine the sentence. He and his assessors conferred for almost 24 hours. About an hour before they reached a decision, Kovalyov was asked in prison whether he would not make a final plea. He refused. The court publicized his refusal directly before the reading of the verdict, on the afternoon of 12 December.

VERDICT AND SENTENCE

The verdict ruled that practically all the items in the indictment had been proved. The subjective aspect — the existence of an intention to subvert or weaken Soviet rule — was seen, despite the denial of this aim by Kovalyov, in the content of the incriminating documents and in the fact that they had been used by foreign propaganda.

The punishment: seven years in strict-regime camps plus exile for three years. The sentence is final and not open to appeal. In a separate decision the court handed over to the procurator’s office materials on the refusal of V. Maresin to give evidence.

*

The investigation and trial of Sergei Kovalyov took place, not in Moscow, but in Vilnius; Kovalyov was tried by the Supreme Court of the Lithuanian SSR, but he was charged according to Article 70 of the RSFSR Criminal Code.

Evidently the authorities wanted there to be fewer spectators at the trial.

On the evening of 8 December, the day before the trial was due to begin, KGB officials in Moscow detained Tatyana Velikanova, Tatyana Khodorovich and Malva Landa as they were driving to the Belorussky Rail Station to take a train to Vilnius. They were detained for some hours in district police stations while ridiculous accusations were made against them to justify their detention; afterwards these were not even repeated. They were released when the train to Vilnius had left and were warned not to try to leave again. Every day, while the trial lasted, they were followed round the clock in an unconcealed manner.

SUPPORTERS IN VILNIUS

In Vilnius, on the morning of 9 December, before the train from Moscow arrived, KGB officials detained Antanas Terleckas, Viktoras Petkus and Valery Smolkin on the station platform, suspecting them of waiting to greet people from Moscow who were coming to the trial. All three were detained at KGB headquarters for half the day and told not to turn up at the court building.

On the day before the trial some Vilnius Jews who had so far been refused emigration visas were told that their cases were being reconsidered and five were given permission to emigrate. They were asked not to go to the trial.

On the morning of 9 December there were 20 to 30 Lithuanians at the court building; many of them had come to the trial from other towns. Neither they nor the people who had come from Moscow and Leningrad were allowed into the courtroom. Only relatives of the accused were allowed in, although officially it was supposed to be an open trial; the other members of the public got in with special passes. Virgilijus Jaugelis (CCEs 34, 36) tried to enter the courtroom but was stopped by one of the KGB officials on duty in the outer hall, who told him to go away. Jaugelis remained standing outside the door of the courtroom. He was taken away and imprisoned for 15 days Tor not obeying the police and insulting them*. However, on 12 December he was released because of fears for his health (Jaugelis had only recently come out of hospital after an operation for cancer; in May 1975 he had been released from a camp on medical grounds).

Mecislovas Jurevicius [CCE 36], who had journeyed to the trial, was sent back to Siauliai, his place of residence.

It is believed that before and during the trial several dozen people were detained in Lithuania.

From the second day of the trial, Lithuanians suspected of wishing to attend the trial, or even of being interested in it, were prevented — if possible — from entering the court building, while those who managed to get into the building were driven out. In the outer hall and corridors over 20 KGB officers were on duty, openly or in plain clothes. These ‘operations’ were supervised by Colonel Kruglov and Lieutenant-Colonel Baltinas, who were almost constantly present in the court building. A police detachment was led by a colonel who was head of the city police force.

The Canadian journalist Levy was not allowed into the courtroom. He referred without success to the fact that Soviet journalists in Canada are allowed to attend trials and also to the [1975] Helsinki Agreements to remove obstacles impeding the work of journalists.

*

On 9 December Academician Andrei Sakharov, who had travelled to Vilnius and, like other people, not been allowed into the courtroom, wrote a declaration to the Supreme Court of the Lithuanian SSR, addressed to the judge in charge of Kovalyov’s case and to Kovalyov himself, as a man conducting his own defence. Sakharov asked to be called as a witness in Kovalyov’s case; his declaration read as follows:

“Having known Kovalyov for many years, I wish to give testimony in court about his exceptional integrity and honesty, his dedication to legality and justice, to the defence of human rights and to openness. My deep respect for S. A. Kovalyov led me to invite him as my guest to the Nobel Prize-giving ceremony in Oslo on 10 December 1975.

“I know that Kovalyov is being charged with giving foreign pressmen materials on the situation of political prisoners in the USSR by publicising them at a press-conference on 30 October 1974, which was chaired by me. This material was in fact handed over by myself, I accept the full responsibility for my action and wish to confirm this in court.

“I am also the author of a letter which is part of the case evidence — the letter to the Head of the KGB, requesting the return of a book belonging to S. A. Kovalyov: Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago.

“I took part in compiling many of the collective appeals which are being used to incriminate S. A. Kovalyov on the ground that they are slanderous. Such a definition of the collective appeals we compiled together seems wrong to me and I should like to explain and expound my point of view in court.”

*

On 12 December, while awaiting the verdict, Kovalyov’s friends issued a declaration in which they described in detail how and why KOVALYOV was being tried, how the trial was being conducted and what infringements of procedural norms had occurred. The declaration describes the trial as “a mere parody of justice”.

Every day arguments arose outside the doors of the courtroom: KGB officials and their assistants kept insulting A.D. Sakharov and other friends of Kovalyov. On 12 December, when the trial was drawing to an end. there were particularly fierce exchanges in the outer hall and later in the street. Some of the ‘guardians of public order’ even tried to provoke ‘physical violence’. However, the following incident also took place. One of the men coming out of the courtroom said quietly, on passing Sakharov: “Forgive us, but it wasn’t Lithuanians who tried him.”

MOSCOW PRESS CONFERENCE

On 18 December 1975, a press-conference about KOVALYOV and his trial was held in Moscow.

The press were given a collection of documents for publication:

- A. Sakharov’s declaration to the Supreme Court of the Lithuanian SSR (dated 9 December 1975);

- Professor V. Kirpichnikov’s declaration to Judge Ignotas (11 December);

- the complaint addressed to the Procurator-General of the Lithuanian SSR by witnesses V.M. Maresin, A.A. Mizyakin, V.F. Turchin, M.M. Litvinov and F.P. Yasinovskaya;

- a declaration by the same persons addressed to the Chairman of the Supreme Court of the Lithuanian SSR (10 December 1975);

- a telegram from Troshin, director of the Cellular Biology Institute, to the administrative head of the Supreme Court of the Lithuanian SSR;

- the speech made by State prosecutor Bakucionis; and

- a record of the morning session in court on the third day of the trial.

Speaking at the press-conference, Academician Sakharov said:

“I should like to emphasize that Kovalyov has been condemned because his conscience moved him to defend other people, who, he was firmly convinced, were the victims of injustice, The charges against him — of aiming to subvert Soviet rule and of libellous activities — have not been proved. The trial was unashamedly unlawful — there was no openness [glasnost], no summing-up by each side, neither defence nor the accused were present, and the defendant gave no final statement.

“Kovalyov had been carefully preparing for a long time to disprove the allegations made against him in the charges, especially those relating to the Chronicle of Current Events. In the seven issues of the Chronicle which figured in the charges there are 694 separate items. The investigators investigated 172 of these. In 11 cases Kovalyov does not exclude the possibility of a mistake. He was preparing to prove that none of these mistakes was premeditated or libellous, 89 items were acknowledged to be accurate even by the investigators, and in 72 cases Kovalyov intended to prove the absence of error in the reports of the Chronicle. However, he was not given the opportunity even to begin on this task and it will be a long time before we learn of his undoubtedly convincing and well-founded arguments.

“In court only seven items were examined, through which the prosecution wanted to prove the libellous nature of the Chronicle. Today we are in a position to assert that only in one or two cases of little significance did the prosecution manage to cast doubt on the accuracy of the reports in the Chronicle.

“The arrest and conviction of Kovalyov are a challenge to public opinion in the Soviet Union and the world.

“After Helsinki [August 1975] and during the Nobel Prize ceremony [award of Peace Prize to Sakharov], the Soviet authorities clearly wished to demonstrate their toughness and the power that allows them to ignore their own laws. To leave this challenge without an answer would mean betraying a remarkable man and also the highest principles on which so much depends. The only possible response is to demand the annulment of the sentence passed on Kovalyov.”