In April 1977 there was a month of prophylactic (preventative) ‘chats’ in Moscow (CCE 45.18). Weeks of ‘preventative chats’ were again held in January 1980 (CCE 56.8) and at the end of January and the beginning of February 1981 (CCE 61.8).

In January 1982 another series of chats took place [note 1].

*

JANUARY

On 5 January 1982 in the evening Yelena Sannikova (CCE 62.8) received a summons, signed by Paramanova, secretary of the district soviet executive committee, asking Sannikova to report to the committee on 6 January. On 6 January Sannikova telephoned Paramanova and asked why no reason had been given for the summons. Paramanova said that she could not reply as there were lots of people around, but she asked her to come without fail.

At the executive committee, the office specified in the summons turned out to be a hall and four people, including Paramanova, were sitting at the presidium table. Sannikova was told that she had been summoned for a talk, to find out where she was working, the name of her boss, how much she earned, why she was not studying. When Sannikova answered that she earned 70 roubles, it was suggested that she could be helped to get a better paid job.

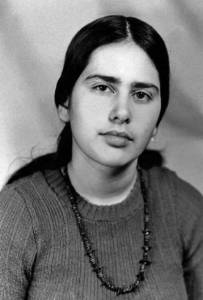

Yelena Sannikova (b. 1959)

Then Sannikova was asked what she had been doing on 10 December 1981 (CCE 63).

Sannikova replied that something strange had happened that day: three people she did not know had come up to her and taken her to a police support point, where she was detained for two hours, then released without being told why she had been detained. Those ‘chatting’ with her asked whether she had recognised any of the people detained at the same time. Sannikova refused to answer the question. Then Sannikova was told of the Moscow City Soviet’s resolution permitting only registered meetings and demonstrations. When Sannikova asked the number and date of this resolution and where it had been published, she was asked for her telephone number so that she could be given this information later. Sannikova declared that her detention had been illegal. They replied that the action of the police had been humane, as criminal proceedings could have been instituted against her for taking part in an illegal demonstration. When Sannikova objected that she had not even been to Pushkin Square, she was told that proceedings could have been instituted against her for trying to take part in a demonstration.

During the conversation two of those present wrote down Sannikova’s replies. Sannikova was also warned not to ‘go there’ next year [note 2].

*

On 18 January Lev Tanengolts (CCE 48) was summoned to the district soviet executive committee. There a committee official asked Tanengolts if he had applied to emigrate. Having received a negative reply, he then said that he had been asked to talk to Tanengolts and warn him that the KGB was interested in him. The reasons for this interest were not stated and Tanengolts got the impression that the official himself did not know what they were. After persistent questioning from Tanengolts the official suggested that telling ‘inappropriate’ anecdotes was the reason.

The same day Tanengolts’s wife Tsarina was invited to the police station; one of the three people who talked to her said he was an official of the district soviet executive committee, the other two were from the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD).

They asked Tanengolts about the aid she provided for prisoners (parcels, printed matter, translations) and where she got the money for this. Tanengolts replied that such aid was not against the law and the expenditure was minimal.

*

On 18 January a police station chief ‘chatted’ with Boris Smushkevich (CCEs 60, 62). The ‘chat’ was rather incomprehensible as the police chief did not quite know what he was supposed to talk about. He asked Smushkevich why he ‘signed letters’, but was unable to say what these letters were about, although he knew that they were in defence of convicted people. He told Smushkevich to draw his own conclusions from the ‘chat’.

*

Maria Petrenko (CCE 56.1-1; CCE 57, 63) was summoned to a police station on 19 January to see Investigator Khlamov as a witness. When she arrived Khlamov left, giving his office over to four people who wanted to ‘chat’ with her. One said he was a representative of the district soviet executive committee, another ‘a representative of the public’; the remaining two did not say who they were.

Petrenko was asked why she signed letters in defence of convicted people, and she replied that she regarded the people she defended as patriots and the criminal proceedings against them as crimes. In reply to a question about her relations with Sakharov Petrenko said that she considered him to be one of the greatest people alive and that she and Sakharov had friendly relations. Veiled threats against Petrenko were made during the ‘chat’.

*

Irina Nagle (CCE 61.1) was summoned to the district soviet executive committee on 19 January together with her mother.

One of the people ‘chatting’ introduced himself as a district soviet executive committee official, the other as KGB official Medvedev. The first was interested in Nagle’s official position, the second in what she was doing on 10 December 1981 in Pushkin Square. In reply to the questions Nagle said that she worked in a private capacity, she did not name her employer, but said she was employed officially.

Nagle asked Medvedev why he was interested in her presence in Pushkin Square on 10 December. Was it against the interests of State Security? Medvedev said that in general it was all right to go to Pushkin Square, but that some people went there with anti-social intentions which were against the interests of State Security. In reply to Nagle’s question of what in fact happened in Pushkin Square on 10 December, Medvedev confessed himself to be ignorant.

*

On 19 January Yefim Epstein had a ‘chat’ with an official at the district soviet executive committee and the Party organiser of the Special Design Office where he works. Epstein was accused of reading, keeping and distributing A Chronicle of Current Events.

During the same period V. Mitskevich, K. Velikanova, I. Kogan (at the Regional Party Committee), V. Lashkova and 0. Kalugina were called in for ‘chats’.

In ‘chats’ with the Jewish refuseniks V. Rozin, Ya. Alpert and V. Fulsakht the main question was of employment for themselves and their families.

*

MARCH-APRIL

On 29 March Leonid Vul (CCE 61) was summoned to the district KGB for a ‘chat’. There he was given a warning ‘according to the Decree’ about the unacceptability of anti-Soviet activity.

*

At the beginning of April Viktor Legler (CCE 62) was told through a third party that the KGB wanted to close the case which had been instituted against him. Legler was told to telephone B.B. Karatayev who invited him for a ‘chat’ which took place on 7 April. Karatayev tried to obtain a statement from Legler about his anti-Soviet activities and remarks and a promise to abstain from this kind of thing in the future. Legler said that he had no intention of breaking the law, but he refused to write the statement. The ‘chat’ lasted about an hour and a half.

*

On 23 April Smushkevich was summoned to the Cheryomushki district KGB. The KGB officials warned Smushkevich about the consequences of signing ‘slanderous’ civil rights letters, referred to the publication of an article about the fund for political prisoners in the paper Voice of the Fatherland and said that the awareness of slander started from the time that one was warned about it, i.e. from that moment.

In April V. Dzyadko was also ‘chatted’ with in the same place.

*

MAY

On 12 May Lina Tumanova (CCE 61) was taken to the Babushkin district KGB. She was told that they had had chats with her more than once in connection with her anti-social activities and that they were now obliged to deliver a formal warning under the Decree of 25 December 1972 [note 1]. In particular she was accused of keeping slanderous and politically harmful literature and giving material help to terrorists. Tumanova [note 3] refused to sign the warning and made a statement concerning the ‘chats’ and the ‘warning’:

‘On 12 May 1982 I was summoned to see the KGB official, Lieutenant-Colonel V.V. Rybakov.

I was cautioned, firstly, in connection with the search carried out at my home in September 1980; secondly, in connection with my open letter in defence of A. Marchenko and I. Kovalev; thirdly, in connection with the assistance I have given to the prisoner I.N. lzvekov.

One. In the record it was stated that I was summoned to the KGB in connection with ‘the existence of information concerning material of a slanderous and ideologically harmful nature kept by her (me). In this connection I state that: 1) The formulation is inaccurate, as it could lead to the conclusion that I have in my keeping documents and material which the KGB considers ‘slanderous and ideologically harmful, at the present time. The KGB does not have information of this kind as of 12 May (12 noon);

2) I do not consider the documents confiscated from me during the search to be either slanderous or ideologically harmful. Some of them were of a purely literary nature, in particular “Belshazzar’s Feast” by Fazil Iskander, Moscow Circles by V. Yerofeyev and Tale of the Troika by the Brothers Strugatsky; some were of a theoretical nature (the collection Self-awareness) and others (The Gulag Archipelago by Solzhenitsyn) contained important historical facts about the Stalinist and post-Stalinist camps.

Furthermore, I request that this confiscated material be returned to me.

Two. As regards the open letter in defence of Anatoly Marchenko and Ivan Kovalyov, I state that the fact that I was summoned to the KGB on 12 May this year once again confirms that my point of view is correct, that our government bodies (in this case the KGB) ‘stop all attempts at criticism of a general nature’.

I am being warned that my ‘activity’ is of a ‘harmful’ nature, although this ‘activity’ consists in attempting to obtain information, in demanding for everyone the right to full information, in expressing criticisms about our legal system and government, and in particular, that I consider and say aloud that articles 70 and 190-1 of the RSFSR Criminal Code are anti-Constitutional and prevent the freedom of speech and criticism guaranteed by the Constitution etc. In fact, I am being warned that for my way of thinking and my openly expressed convictions, criminal proceedings can be instituted against me under article 190-1 and article 70.

Three. Comrade Rybakov showed me the record of the trial of I.N. Izvekov, from which it appears that I.N. Izvekov, to whom I have sent money in camp, has been convicted for having exploded a home-made device outside the doors of the district military registration office in Kuibyshev. If I.N. lzvekov did in fact explode a device then I must state that I am against all acts of a terrorist nature as they are contrary to my own beliefs. But this does not mean that I will cease to provide such assistance for I.N. Izvekov as I am able, as I believe that aid to any prisoner is an act of charity and humanity.

Warnings in connection with providing aid to a prisoner I consider to be illegal and inhumane. I consider it necessary to state that not one of the articles of the RSFSR Criminal Code includes measures to be taken for aiding prisoners.

During the ‘chats’ comrade Rybakov maintained that the Fund was connected with [foreign] intelligence services and that its money came from, ‘among others’, intelligence services. I categorically deny this statement and see it as an attempt to slander the activities of the Fund for Political Prisoners, activities which are undoubtedly humane and absolutely legal.

Addendum. In point two, by my open letter in defence of A. Marchenko and I. Kovalev I mean the text of the Radio Liberty broadcast of 13 December 1981, which I have seen, and which includes the text of my open letter.

*

On 14 May Rushania (Roza) Fedyakina (CCEs 60, 61) was summoned to the district KGB. There she was given a warning ‘according to the Decree‘ [note 1]. She was accused of ‘contacts with foreigners outside working hours’ and keeping ‘politically harmful’ literature. Fedyakina refused to sign the record.

*

JUNE

On 22 June 1982, Vladimir Golovach was called to the KGB for a ‘chat’. He was told that the KGB was aware that he was keeping samizdat and tamizdat. Then Golovach was taken home accompanied by KGB officials and voluntarily handed over poems by Mandelshtam, a book by Nabokov and Doctor Zhivago by Pasternak, saying that he had nothing else and that those books had been sent to him by the Klinsky family who had recently emigrated from the USSR.

He was told that it was clear that what he had handed over was not everything and that the KGB knew all about him. It was suggested that he should come back sometime and hand in the rest. During the ‘chat’ something along the following lines was said: ‘We have new leaders and we will liquidate all samizdat and all stores of anti-Soviet literature’.

Golovach used to work at the Institute of Management Studies at the USSR Academy of Sciences. In 1981 the director of the Institute, Academician Trapeznikov, reprimanded him for absenteeism. Golovach was forced to leave and for a long time couldn’t find a job in his field, but two months ago took a job as a programmer. In the last two or three months many of his present and former colleagues have been summoned to the KGB for ‘chats’ and asked if Golovach had given them any books of a slanderous or anti-Soviet nature.

Golovach was fired from his new job because of ‘staff reductions’. The KGB continues to call him in for ‘chats’. The books confiscated from Golovach have been classified by KGB officials as ‘decadent and ideologically harmful literature, handed in voluntarily’.

======================================

NOTES

[1] ‘Prophylactic’ chats with the KGB were formally introduced in the early 1970s as a way of intimidating a variety of activists without charging them or imposing terms of imprisonment. Following the adoption by the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet of an unpublished law in December 1972 — see “The Bukovsky Archive” (16 November 1972) for detail and background — the KGB issued formal ‘warnings’ to such people.

If they did not heed these alerts, charges might be brought against them for certain common offences, e.g., Article 190-1, investigated by the police, and the more serious Article 70, investigated by the KGB (both laws were part of the RSFSR Criminal Code). See CCE 30.13 (1973) for a first account of the decree and its implementation.

[2] Yelena Sannikova was sentenced in October 1984 under Article 70 to a year in a strict-regime camp and four years exile (see USSR News Update, 19/20-15).

[3] Lina Tumanova was arrested in July 1984 but released two months later on condition that she did not leave the country. She died of cancer on 15 April 1985 (see USSR News Update, 1985, 7/8-2).

===================