Samizdat is a specific medium for exercising freedom of expression in our country.

During the last few years samizdat has evolved from a predominant concern with poetry and fiction towards an ever greater emphasis on journalistic and documentary writing.

This is particularly true of 1968.

*

INTRODUCTION

This year samizdat has not been enriched by a single major prose work [1], as it was in past years by such works as Solzhenitsyn’s novels, the memoirs of Eugenia Ginzburg, collections of stories by Shalamov, and novels by Lydia Chukovskaya, Vladimir Maximov and others.

During the year no literary miscellany such as Syntaxis or Phoenix [2] has appeared.

On the other hand, during 1968 readers of samizdat, who are also its volunteer publishers, have received a regular flow of documents, Open Letters, speeches, commentaries, articles, news items, and so on.

In addition to its role as a supplier of books, in other words, samizdat has begun to carry out the functions of a newspaper [3].

*

The following survey will probably not be a full one.

The notes on some of the materials, furthermore, are too brief. This is due to the force of circumstances, however, and does not mean they are of lesser importance.

We have not always been consistent when deciding whether to include various materials from 1967 which were circulated mainly in 1968. Yet the Chronicle feels that giving readers a survey of the samizdat now in circulation is so important a task that it does not wish to allow considerations of a formal bibliographical nature to restrict its choice.

*

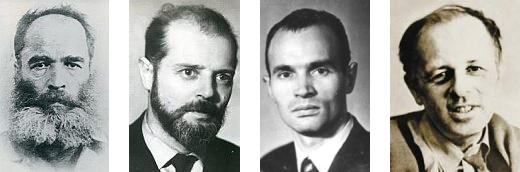

Kostyorin, Yesenin-Volpin, Marchenko, Sakharov

*

TWENTY-NINE ENTRIES

About Czechoslovakia (1-2)

[1]

Translations from Czechoslovak articles and documents

The first document to appear in this category was a speech made in 1967 by Ludvik Vaculik at the 4th Congress of Czechoslovak Writers. It gave a detailed account of the workings of a totalitarian regime.

Attacking an undemocratic regime based on the triumph of “mediocrities”, Vaculik emphasized in the strongest terms that “in criticizing the State regime, I am not casting aspersions on the ideals of socialism, for I am not convinced that all that has happened in this country was inevitable and, furthermore, I do not identify the power in question with the idea of socialism …”

In the spring and summer of 1968, a great variety of materials from Czech and Slovak newspapers and periodicals was circulated. Among them were: interviews with the widows of Slansky and Clementis (Communist leaders executed in 1952), and other materials about the trials of the 1950s; speeches by Dubcek, Smrkovsky, Cisar and other leaders of the Czechoslovak Communist Party. Particularly important was that samizdat made available the full text of the declaration known as “Two Thousand Words”: in the official Soviet press it was described in a misleading way. Samizdat has also put into circulation an example of a truly free, non-totalitarian polemic, Joseph Smrkovsky‘s “One Thousand Words in Reply to Two Thousand Words”.

The “Czechoslovak Spring” was interrupted by brute force at the end of the summer.

Several samizdat documents relate to the first days of the occupation: leaflets addressed to Soviet soldiers, and messages to the population. “On the third day of this treacherous aggression we are still free,” begins a message from the historians of Prague to their fellow-citizens: “this brutal invasion has not brought our people to its knees.”

In the months since the Moscow Agreement (26 August 1968), unfortunately, very few Czechoslovak materials have come into circulation via samizdat. The most important was the speech by Joseph Smrkovsky on 29 August, in which the President of the Czechoslovak National Assembly said outright that “the country has suddenly been occupied by overwhelming military force”.

He admitted that the Czechoslovak leaders in Moscow had been forced to accept a tragic compromise, but it had been dictated not by cowardice but by a feeling of responsibility towards the country’s population. “The talks and the decisions arrived at weigh heavily on our shoulders,” Smrkovsky said in conclusion. “We are obliged to conduct this debate in the shadow of the tanks and aircraft that have occupied our country. The only way out of these difficulties is through the unity of the people and the government, through obedience to the call: ‘we are with you, as you must be with us’.”

Of the later documents one may mention the appeal of the Czech writers of 31 October and the “Ten Points” of the Students’ Union of Bohemia and Moravia which formed the political basis of the student strike of 18-20 November. The Ten Points are an expression of complete support for the “action programme” of the Czechoslovak Communist Party; they condemn any return to press censorship and government by an inner caucus, and demand guarantees of civil rights and liberties.

*

[2]

Open Letters and articles by Soviet authors about Czechoslovakia

Before the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, at the end of July 1968, when the Soviet press was conducting a particularly violent campaign against the democratization in Czechoslovakia and when the threat of intervention seemed more real than at any time before or after, there had already appeared two documents expressing sympathy for Czechoslovakia and indignation at the propaganda campaign:

- a letter to all members of the Czechoslovak Communist Party and the whole Czechoslovak people (CCE 3.1) signed by five Communists (P. Grigorenko, A. Kostyorin, V. Pavlinchuk, S. Pisarev and I. Yakhimovich);

- an Open Letter by Anatoly Marchenko (CCE 3.1) to the Czechoslovak newspapers Rude pravo, Prace and Literarni listy.

The sending of Soviet troops into Czechoslovakia (under the guise of “fraternal help”) was unanimously approved in the pages of the Soviet press. It met with various forms of protest from individual Soviet citizens.

Among the samizdat reactions to these tragic events we may mention:

- Ivan Yakhimovich‘s letter;

- “September 1969” by Valentin Komarov;

- “The Logic of Tanks”, by an anonymous author;

- “An appeal to Communists” signed “Communist’;

- a letter by P. Grigorenko and A. Kostyorin; also

- a letter to the Party’s Central Committee from Alexei Kostyorin. He is resigning from a Party “which has become the gendarme of Europe’.

All these documents, though differing in style and form, make the same points:

- (a) the intervention in Czechoslovakia is the result of a revival of Stalinism;

- (b) the real reason for it was a wish to suppress democratization, freedom and the rule of law, and to destroy a dangerous experiment, combining socialism with democracy;

- (c) the invasion was a moral defeat for the occupiers;

- (d) our people and intelligentsia are collectively responsible for what has happened, and all honest, thinking people in our country must unite.

*

[3]

The Trial of Ginzburg, Galanskov, Dobrovolsky and Lashkova

The main letters on this trial (CCE 1.2) were listed in the first issue of the Chronicle.

In addition, there are samizdat versions of the speeches by defence lawyers Zolotukhin and Kaminskaya, as well as the final pleas of defendants Alexander Ginzburg and Yury Galanskov, for whom they appeared.

*

There is also a letter to the editors of Literaturnaya gazeta from Vadim Delaunay.

From knowledge of the preposterous evidence given by Dobrovolsky in the investigation of the case in which he (Delaunay) was implicated together with Bukovsky and Kushev, he shows that the sentences in the Ginzburg-Galanskov trial were based on false evidence by Dobrovolsky.

Also circulating in samizdat are letters sent by various people to Larissa Bogoraz and Pavel Litvinov after their statement about the Galanskov trial (CCE 1.2 [1]), the best known of which is a letter signed by twenty-four schoolchildren.

*

[4]

Among those listed in Chronicle No. 2 as having been subjected to extra-judicial repression were the schoolteachers Yury Aikhenvald and Valeria Gerlina (his wife; CCE 2.1 [1, 19]).

They were dismissed from their jobs after signing a letter [4] about the trial. Their dismissal was carried out in such a flagrantly illegal way that after a court order was issued the school had to reinstate them.

The record of discussions of Gerlina’s case, at a trade union meeting at her school and in the education department of the local soviet, is circulating in samizdat. It is of purely documentary value, showing how little legality means to the mass of educated people. This record is also one of the few documentary works of the past year which can be read both for literary pleasure and the information it offers.

*

[5]

Forcible psychiatric-hospital confinement of Volpin and Gorbanevskaya

This event was reported in the first issue of the Chronicle.

The confinement of Volpin in a mental home (CCE 1.3 [2]) gave rise to a whole number of documents:

- the note which Alexander Volpin left for his wife when he was taken from his home;

- a record of his conversations with the doctors;

- his appeal to his friends;

- a letter from his wife, Victoria, to the USSR Minister of Health, B. V. Petrovsky;

- a Letter from 99 Mathematicians (CCE 1.3 [12]) in Volpin’s defence;

- a note written by his wife and mother, about the conditions under which he was held in the hospital;

- the text of the order by which Volpin was forcibly confined, and

- other materials.

The story of how Gorbanevskaya was sent to a mental hospital is told in her own account entitled “Free Medical Aid”.

*

[6]

25 August 1968 demonstration on Red Square

The main letters connected with this event (CCE 4.3) were listed in the Chronicle.

In addition, there is now a letter addressed to the deputies of the USSR Supreme Soviet and the RSFSR Supreme Soviet. The main point in this letter is that the sentences imposed on five of the demonstrators are an infringement of fundamental civil rights.

The letter was signed by 95 people. They include: leading actor Igor Kvasha; writer on church affairs A. Krasnov (Levitin); A.A. Neifakh (D.Sc., biology); writer Victor Nekrasov; historians Leonid Petrovsky and Pyotr Yakir; L. Pinsky (D.Sc., philology); and the pianist Maria Yudina.

Some of the most striking samizdat items of 1968 were the final pleas at the trial of the demonstrators (CCE 4.1) — Larissa Bogoraz, Pavel Litvinov, Vadim Delaunay, Vladimir Dremlyuga and Konstantin Babitsky — and the speech made in her own defence by Larissa Daniel (Bogoraz).

*

[7]

The Pushkin Square demonstration of 22 January 1967

Documents assembled by Pavel Litvinov.

Included are verbatim records of the trial of Victor Khaustov and of Bukovsky, Delaunay and Kushev. A number of other documents, circulating in samizdat since early 1968, are reproduced in this collection.

In the autumn it was also published (in Russian) in London. Unfortunately, that edition – for some unaccountable reason – omits the letter by P.G. Grigorenko which forms the logical conclusion to the whole collection. (His letter is included in the English-language edition).

*

SAKHAROV’s “REFLECTIONS” (8-9)

[8]

Andrei Sakharov

Reflections on Progress, Peaceful Coexistence & Intellectual Freedom [5]

The author of this study, an Academician and “Father of the H-Bomb”, attempts a rigorous and objective approach to world problems.

He shows that the world is threatened by a number of dangers: thermonuclear destruction, famine for half of humanity, uncontrolled changes in the environment, threats to intellectual freedom, the growth of racism and nationalism, and the emergence of dictatorial regimes.

In Sakharov’s opinion the only solution is to be found in overcoming the divisions among humanity: attempts to bring the two economic systems [capitalism and communism] closer to each other, an intellectually rigorous, objective and democratic approach to the formulation of domestic and foreign policy, intellectual freedom, aid to underdeveloped countries through a drastic reduction in military expenditure, and the observance of geo-hygiene.

In line with these basic propositions Academician Sakharov makes concrete recommendations to the leaders of our countries.

*

[9]

“TO HOPE OR TO ACT?”

Sakharov’s study has evoked a response from members of Estonia’s technical intelligentsia in an article entitled “To Hope or to Act?” [6].

They maintain that Sakharov “puts too much faith in scientific and technical means, in economic measures, in the goodwill of those who control society, and in people’s common sense”, and that “the root causes he sees and the remedies he advocates are external, material ones, while the inner, spiritual, political and organic ones are ignored”. The article says that what we need most of all is a moral revival of society, since, “having destroyed Christian values, the materialist ideology has not created new ones”.

This has given rise to a society in which solidarity is an external, mechanical thing, and one which is actually based on socially alienated individuals who are fearful of their neighbours and feel insignificant and lonely before the state machine. New moral values are essential. The authors of the article demand not only intellectual freedom, but also political freedom, real democracy and a renunciation of the doctrine of militant, aggressive communism in foreign policy. The authors of the article conclude that the “leading minds of our society” should apply themselves to working out new social, political and economic ideals.

*

[10]

Appendix to Anatoly Marchenko’s “My Testimony”

(These items are included in the 1971 Penguin pbk edition, pp. 381-430.)

Marchenko‘s book gives an account of the life of Soviet political prisoners during the 1960s. It entered circulation in 1967.

One can form a partial idea of it from the letter by Marchenko (CCE 2.6) in Chronicle No. 2.

With a number of other documents, this letter forms part of an appendix to the book: it was compiled in autumn 1968, when Marchenko was sentenced for infringement of the identity-document (‘passport’) regulations and sent to a strict-regime camp in the north of the Perm Region.

The appendix includes:

- Marchenko’s letter to Chakovsky, chief editor of Literaturnaya gazeta (the weekly “Literary Gazette”), in response to a phrase about political prisoners being “kept at public expense” in the latter’s “Reply to a Reader”;

- Marchenko’s Open Letter (CCE 2.6) to the President of the Soviet Red Cross & Red Crescent Societies and a number of other officials about the situation of political prisoners; the reply to this letter from F. Zakharov, Vice-President of the Soviet Red Cross Executive Committee;

- Marchenko’s Open Letter to Czechoslovak newspapers;

- a statement by eight friends of Marchenko concerning his arrest;

- Larissa Bogoraz‘s letter, “On the arrest of Anatoly Marchenko”; and a statement by the same author in connection with the arrest of Irina Belogorodskaya (CCE 3.1 [1]).

*

[11]

Documents concerning Solzhenitsyn

These consist of: Veniamin Kaverin’s letter to Konstantin Fedin; Solzhenitsyn’s correspondence with the secretariat of the Union of Soviet Writers; and a record of the discussion in the secretariat of his novel Cancer Ward.

For an account of these documents, see Chronicle No. 2 (CCE 2.5).

*

[12]

Two Letters by Lydia Chukovskaya

The first Letter, “Not an Execution, but Thoughts, Deeds”, was written in connection with the 15th anniversary of Stalin’s death. It concerns the threat of a revival of Stalinist methods of ideological repression.

The second Letter, “The responsibility of a writer; the irresponsibility of Literaturnaya gazeta”, is concerned with Solzhenitsyn, his readers and his critics.

*

P.G. GRIGORENKO (13-15)

[13]

Letter from Petro Grigorenko to KGB chairman Andropov

An account of the author’s “prophylactic chat” at the KGB.

*

[14]

Grigorenko Speech at the dinner

in honour of Alexei Kostyorin’s 72nd birthday

This speech is about Kostyorin’s life, the support which he has given to the cause of the Crimean Tatars, and the tasks confronting their movement [7].

*

[15]

The Funeral of Alexei Kostyorin

The writer Alexei Yevgrafovich KOSTYORIN died on 10 November 1968.

A member of the Soviet Communist Party since 1916, a former prisoner of Stalin’s camps, and an active fighter for the rights of men and justice for small nations, Kostyorin was buried on 14 November. Between three and four hundred people attended his funeral [8].

The samizdat booklet on this event consists of:

- The chief compiler’s (Pyotr Grigorenko) preface;

- A written description of the funeral (“Yet another mockery of sacred feelings”) by P.G. Grigorenko;

- An obituary written by a group of Kostyorin’s friends, which was read out by Anatoly Jakobson at the morgue of the Botkin Hospital, Moscow;

- Speeches given at the morgue: Muarrem Martynov, Crimean Tatar poet; S. P. Pisarev, Communist Party member since 1920; Ablamit Borseitov, school-teacher; and Reshat Dzhemilev, engineer;

- Speeches at the crematorium: Professor Refik Muzafarov (D.Sc., philology; see CCE 25.9 [2]), and P. G. Grigorenko (Cand.Sc., military sciences);

- Speeches at the subsequent memorial meeting: Pyotr Yakir, historian; Khalid Oshayev, Chechen writer; Andrei P. Grigorenko, technician; Zampira Asanova, medical doctor; Leonid Petrovsky, historian; and an unknown man to whom the compilers of this collection of documents have given the pseudonym “a Christian”.

*

CRIMEAN TATARS (16-17)

[16]

Crimean Tatar representatives in Moscow

Newsletters

In 1968, as in past years, these Newsletters continue to describe the activities of the Crimean Tatars’ representatives in Moscow, and to provide information about the persecution of individual members of the movement as well as about large-scale acts of repression, such as the events in Chirchik (Uzbekistan) on 21 April 1968 and in Moscow on 16-17 May.

The Newsletters also contain various appeals by the Crimean Tatars’ representatives to cultural figures and to world public opinion. One of these appeals was reproduced in Chronicle, No. 2 (CCE 2.4).

*

[17]

Anonymous

Crimean Tatars on Trial

This pamphlet describes the tragic expulsion of the Tatars from the Crimea (1944), the struggle they have waged for their rehabilitation and recent repressive court proceedings in which

“every document containing information about the national movement … is regarded by the local authorities as being anti-Soviet, while peaceful demonstrations and meetings … are described as ‘mass disorders’.”

The author of the pamphlet recalls the events in Chirchik (Uzbekistan), police raids in Moscow and the Crimea, and the suppression of the national movement for justice for the Crimean Tatars.

*

[18]

Nikolai Alexandrov

“Our Short Memory” [9]

A pamphlet about historical “forgetfulness”, which is not only an insult to the memory of millions of innocent victims, but also a real threat to the future of our people.

*

KRASNOV-LEVITIN (19-22)

[19]

Anatoly Krasnov-Levitin

Christ and the Master

is an attempt to discuss several basic questions of Christian teaching through a literary and philosophical study of Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel The Master and Margarita. The thread of the argument is provided by the chapters in the novel about Christ. The book is written in a free, discursive manner with frequent digressions into the author’s personal reminiscences and reflections.

*

[20]

Stromati

The Greek word stromati literally means “carpet’, but in the figurative sense of “miscellany” it was used by various ancient teachers of the Church as the title for their books.

Written in the form of observations loosely tied together by the general theme of the part a Christian should play in society, Krasnov’s book deals with such questions as the moral responsibility of a Christian to society, the role of the Church in the life of society, and the collaboration of Christians with people of different views in the solution of common moral and political tasks. The author gives a brief survey of the various political trends at the present time and states his attitude towards them. At the end of the book the author gives his political credo, which he defines as “democratic humanism’, and calls on people of different persuasions to unite on this basis.

*

[21]

“The situation of the Russian Orthodox Church”

Krasnov’s letter is addressed to the Pope, and it gives an account, based mainly on the author’s personal observations, of the attitude of different generations of Russians to religion and the Church, the way in which some young people are turning to the Church, and the relations between different faiths.

He raises the need for an inner revival of the Russian Orthodox Church, and examines the difficulties in the way of this. The author speaks of the criticism which he and others have made of the Russian bishops, and contends that such criticism is both justified and necessary. The question of uniting the Western and Eastern Churches is also touched upon in this letter.

*

[22]

“A Drop under the Microscope”

This article is about the difficulties which have arisen at the parish level in the Russian Orthodox Church as a result of a change in the parish administration. This change consisted of taking the administration of parish affairs out of the hands of the priest and transferring it to the council of twenty laymen headed by a church elder.

The author shows that this reform is in conflict with canonical tradition, and he points out the practical consequences which it entails in conditions of constant interference by the authorities in the life of the church: infringement of the rights of the priest, unchecked power for the elder, who is appointed by the state authorities, etc. As an illustration, the example of the Nikolo-Kuznetskaya church in Moscow is described in detail. The author also treats the more general question of the way in which the Russian Orthodox Church has been denied its rights in the Soviet Union, and of the responsibility of the Church hierarchy itself for this state of affairs.

*

[23]

Father Sergy Zheludkov

Two letters from the Pskov Priest

In a letter to Pavel Litvinov, Zheludkov expresses his support for the appeal by Pavel Litvinov and Larissa Daniel (Bogoraz), “To World Public Opinion” (CCE 1.2), and speaks of the aims shared by all “people of goodwill”, irrespectively of how they define their views.

*

His “Letter on the Day of St Nicholas and Victory Day” (9 May 1968) is addressed to the heads of various foreign churches. It was written after reading Anatoly Marchenko‘s book My Testimony (1967).

Referring to this book, the author speaks of the grievous situation of political prisoners in the USSR and he calls on all Christians, and particularly their spiritual leaders, to speak up in their defence.

*

[24]

Archbishop Yermogen

Letters to the Patriarchate

The first of the letters by Archbishop Yermogen to the Patriarchate, in which he disputes the legal validity of his dismissal, was written in November 1967; the second in February 1968.

In these letters he not only shows the illegality of his dismissal, brought about under pressure from the authorities as a reprisal for his staunch resistance to actions detrimental to the Church; he also attempts an analysis, from the point of view of both canon and secular law, of the whole question of relations between Church and State in the USSR.

“On the 50th anniversary of the re-establishment of the office of Patriarch:

notes on its historical, canonical and legal aspects”

There is an even more detailed study of this question in his article “On the 50th anniversary of the re-establishment of the office of Patriarch” (25 December 1967) which makes numerous references to the decisions of the Ecumenical and National Councils of the Orthodox Church, including the 1917-1918 National Council of the Russian Church.

*

[25]

Open Letter

to the Kiev community of Baptists & Evangelical Christians

This letter is the latest in a series of similar letters which appeared in 1967 and is in defence of the Baptist preacher Georgy P. Vins who was arrested in 1967 [10] and is being subjected to cruel treatment in a camp.

The letter is signed by 176 members of the community in the name of four hundred Baptists and Evangelical Christians in Kiev.

*

[26]

Boris Talantov

“Statement to the USSR Procurator-General”

This statement contains protests against the persecution to which the author, who lives in the city of Kirov (Volga District), is being subjected for his opposition to interference by the Soviet authorities in the affairs of the Russian Orthodox Church, and against the acquiescence in this interference by the church hierarchy.

*

[27]

Grigory Pomerants

“Three Levels of Being”; “Man of Air”

The first article is about the roots of religious feeling in human beings. The author examines the various levels of being which arise with the awakening of different of the human psyche. concludes that there is an “amorphous” mystical sense of religion, concludes the author, which is beyond the Church and not limited to dogmas and Holy Scriptures.

*

The second article is about the concept of “the People” or Nation [narod]. The author concludes that the concept has no real content.

*

[28]

VERSE

In 1968 there were three new collections of verse: Alexander Galich, Book of Songs; Natalya Gorbanevskaya, The Wooden Angel, verse of 1967; and Yuly Daniel, Verse of 1965-7.

Apart from these there are, as usual, many individual poems circulating in samizdat – they include “Farewell to Bukovsky” by Vadim Delaunay, and several poems by unknown authors written under the impact of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia.

*

CHRONICLE (Nos 1-4)

[29]

Human Rights Year in the Soviet Union (“A Chronicle of Current Events”)

FOUR ISSUES

*

Description of the trial of Yury Galanskov, Alexander Ginzburg, Alexei Dobrovolsky and Vera Lashkova. A list of the main Soviet newspaper articles on the trial. A list of the main letters concerning the trial. Information about the first cases of reprisals against signatories of such letters. The appeal to the Presidium of the consultative conference of Communist Parties in Budapest.

Information about the trial of the members of the All-Russian Social Christian Union for the Liberation of the People. News in brief.

*

Cases of extra-judicial political persecution in 1968. Appeal from the Crimean Tatars to world public opinion. Materials on Solzhenitsyn. Letter by Anatoly Marchenko about the situation of political prisoners, and the reply from the Soviet Red Cross. News in brief.

Corrections and additions to Chronicle No 1.

*

The shortest issue of the Chronicle, concerned almost entirely with events during the Invasion of Czechoslovakia and those preceding but closely linked with it.

There is information about the arrest of Anatoly Marchenko and his trial; about other arrests in Moscow and Leningrad; about various forms of protest against the occupation Czechoslovakia (including the demonstration on Red Square), and about the trial of Boguslavsky, a Leningrad resident.

*

Court proceedings in the case of the 25 August 1968 demonstration on Red Square. Exile for Babitsky, Bogoraz and Litvinov. Short commentary, the Soviet press on the trial, samizdat documents concerning the case.

Information about some political prisoners condemned for “Betrayal of the Motherland” (Article 64). A “new” method of conducting house searches. A supplement to the collection of materials on the Sinyavsky-Daniel the “White Book”). News in brief.

=============================================

NOTES

First publication in English, Uncensored Russia (1972), Chapter 18, “The World of Samizdat” (pp. 350-351).

*

- A reference to notable prose works appearing in samizdat during previous years (L. = London; N.Y. = New York). Several were included in Michael Scammell (ed.), Russia’s Other Writers, 1970:

— Eugenia Ginzburg, Krutoi marshrut (Grani 64, 1967, Frankfurt); Into the Whirlwind (L. 1967);

— Shalamov stories (Novy zhurnal 1966-1970, N.Y.); two in Scammell (1970);

— Lydia Chukovskaya, Opustely dom (Paris 1964); The Deserted House (L. 1967);

— Alexander Solzhenitsyn, V kruge pervom (1967); The First Circle (L. 1968);

— Vladimir Maximov, Dvornik Lashkov (Grani 64, 1967); House in the Clouds, Scammell (1970).

Tamizdat dates, i.e., publication abroad in Russian, give a rough indication as to when the work was circulating in the USSR.

↩︎ - Compiled, respectively, by Alexander Ginzburg and Yury Galanskov (CCE 1.1).

↩︎ - Two years later (December 1970), a KGB report to the Politburo echoed this shift from literature to journalism in the contents of samizdat: 15 January 1971* (St 119-11).

↩︎ - “The Letter of 170” (224 signatories), enclosing the appeal by Bogoraz and Litvinov, was written, signed and sent to the USSR Procurator-General after the trial was over (CCE 2.1 [3.2]).

↩︎ - This text appeared in the New York Times in English (22 July 1968). It was described as “An Essay …”

↩︎ - Two documents reached the West at the end of 1968.

The first (“To Hope or to Act?”), concerned Sakharov’s well-known Reflections on Progress (above, item 9). The document from Estonia put forward ideas somewhat more radical than the Chronicle’s summary would suggest.

Written soon after the Czechoslovak occupation, it warned:

“For twelve years, since the 20th Party Congress [1956], we have been waiting and asking our leaders for liberating reforms. We are prepared to ask and wait for a certain time longer.

“But eventually we will demand and act! [CCE 10.5]

“And then tank divisions will have to be sent not into Prague and Bratislava but rather into Moscow and Leningrad!”

The Russian text of “To Hope or to Act?” was published abroad in Possev No. 1, 1969, Munich; an English translation appeared in Frontier, London (Vol. 12, No. 2, May 1969).

*

The second document was an “Open Letter to the Citizens of the Soviet Union” (dated September 1968) and signed “Gennady Alexeyev, communist”. It made various similar points from a more Marxist position.

↩︎ - In 1968 Crimean Tatars in Moscow held a birthday party for Alexei Kostyorin (1896-1968) on 17 March. Outraged by the invasion of Czechoslovakia on 21 August, Kostyorin had just resigned from the Soviet Communist Party: he did not want, he said, to be attached to “the gendarme of Europe”.

Seriously ill, Kostyorin asked ex-Major General Petro Grigorenko (1907-1987) to attend the party and speak instead.

↩︎ - “I have known Alexei Kostyorin for a very short time. Less than three years. Yet we have lived a whole life together.

“While Kostyorin was still alive, someone extremely close to me said, ‘You were made by Kostyorin’. And I did not object. Yes, he made me: he turned a rebel into a fighter. I will be grateful to him for this to the end of my days.”

Thus spake Grigorenko at Kostyorin’s funeral in November 1968.

It was a remarkable occasion for which Crimean Tatars, Chechens, and even Volga Germans had journeyed thousands of miles; and, prolonging an old tradition, it also became a political demonstration.

*

Kostyorin spent three years in Tsarist jails, and a further 17 years (1938-1955) in Soviet prisons, camps and internal exile. After his release a few of his stories and essays appeared (often severely censored) in Novy Mir and elsewhere.

He was the father of Nina Kostyorina [Kosterina] who was killed in the war. Her Diary is a Soviet equivalent of The Diary of Anne Frank. (In Russian, Novy mir excerpts, December 1962; English translation, The Diary of Nina Kosterina, Crown publishers, 1968.)

Just before his death Alexei Kostyorin not only resigned from the Party: he was also surreptitiously expelled from the Writers’ Union.

↩︎ - Circulated, allegedly, by Revolt Pimenov (1970, CCE 16.2).

↩︎ - Correction: Vins was arrested on 19 May 1966 and sentenced that November to three years in the camps. (See Georgy Petrovych VINS entry in KHPG “The Dissident Movement in Ukraine”.)

↩︎

================================