The Trial of Lapienis, Matulionis and Pranskunaite

Vladas Lapienis and Jonas Matulionis were arrested in Vilnius on 20 October 1976. (Not 19 October; in CCE 44.22 there was an error here.)

*

The same day a search was carried out in Panevėžys (CCE 44.22) at the home of Ona Pranskunaite (CCE 45.10 & CCE 46.7). In January 1977 she was arrested (CCE 45.10).

Lapienis (b. 1906), Matulionis (b. 1921) and Pranskunaite (b. 1936) were held in the KGB investigation prison in Vilnius. The investigation was at first in Case 345, begun in June 1975 (the case of the Chronicle of the Lithuanian Catholic Church [LCC Chronicle]). Before the trial it was made into a separate case.

Ona Pranskunaite continued to refuse to give evidence in prison, in particular to name the people who had worked on the ERA duplicating machine found in her flat together with duplicated prayer books (CCE 44.22) and those who gave her LCC Chronicle to re-print. The investigators threatened her with a psychiatric hospital for not giving evidence.

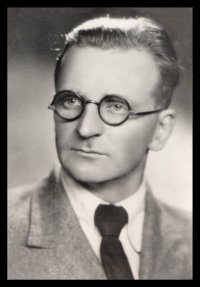

Vladas Lapienis (1906-2012)

*

Lapienis was allowed to write letters to his wife from prison. In them he informed her about his health (which had got considerably worse) and about the fact that, despite his indisposition, he was strong in spirit, and he communicated his meditations on religion.

The case was heard in the Lithuanian Supreme Court on 20, 22 and 25 July 1977. Lapienis was charged under Article 68 of the Lithuanian Criminal Code (=Article 70, RSFSR Code), Matulionis and Pranskunaite under Article 199 pt. 1 (= Article 190-1).

The date of the beginning of the trial was kept secret: the wife of Lapienis, Elena Lapieniene, who was appearing as witness, received a summons only the day before the trial. The public was allowed into the court-room, but they were not allowed to sit in the front rows, as a result of which much of it could not be heard.

*

CHARGES

Vladas Lapienis was charged with writing anti-Soviet articles and statements and inserting them in LCC Chronicle, and also with circulating LCC Chronicle. He was also charged with circulating The Gulag Archipelago in Lithuanian translation. According to the evidence of witness Ruzgiene from Utena (she confirmed this at the trial) Lapienis had given her a typewriter and asked her to re-type the book.

Another episode in the indictment was keeping “a slanderous article about a statesman”. This was how the trial materials referred to an article circulated in Lithuanian samizdat, “Mikhail Suslov, Hangman the Second”. This describes the punitive activities of Suslov in his post as Chairman of the CPSU Central Committee Bureau for Lithuanian Affairs (1944-1946), comparing them to the activities of Mikhail Muravyov, nicknamed “the Hangman” for his suppression of the 1863 uprising.

Jonas Matulionis was charged with editing texts for LCC Chronicle: according to the charge, he was drawn into this work by Lapienis, who gave him the texts.

Ona Pranskunaite was charged with re-typing several numbers of LCC Chronicle on a typewriter and circulating them in Panevėžys and other towns. (The ERA duplicator was mentioned in the charge, but not the duplication of prayer books.)

During one of the breaks everyone was cleared from the court room and when they were allowed in again it turned out that Lapienis had already made his final address. Nevertheless, the text of his final address (10 pp.) was circulated in Lithuanian samizdat and published in full in LCC Chronicle (29). Lapienis said:

“I am charged with ‘preparing articles and statements which contain slanderous fabrications defaming the Soviet system’. … I have never written any articles … Indeed, after the illegal actions of certain employees of State Security, after the search of 20 November 1973 and interrogations, I wrote certain declarations … I pointed out that the KGB had taken away from me a typewriter, manuscripts and religious books which have nothing in common with a criminal case, while the greater part of them were not recorded either in the search protocol or in the list appended … Then at interrogations they tried to obtain evidence from me by threats, lies, cunning and other illegal actions.”

Lapienis said that in chatting with him on many occasions about these declarations (and having returned to him a part of what was confiscated — according to the materials of his case he found out that the remainder had been burned), officials of the KGB and the procurator’s office never found anything slanderous about them:

“… How could these declarations, which have been lying for three years or more in the archives, have suddenly become slanderous in 1977?”

Lapienis said that he could not bear responsibility for the fact that his declarations exposing these actions had been published in LCC Chronicle, as they were not secret. During this Lapienis denied the charge that LCC Chronicle was “illegal”. The publication exercised the legal right of believers to self-defence from persecution, he said, and from malicious attacks by anti-religious propaganda (he offered vivid examples), and from the tyranny of bureaucrats.

Lapienis also spoke about the prejudiced nature of the investigation. It attached the the label ‘anti-Soviet’ to any manifestation of dissent; it did not engage in a factual investigation of what was truth and what lies, and where the slander lay in these or those texts:

“To defend the Church and believers is not politics but the sacred duty of every Catholic …, to be sentenced for fulfilling my obligations is for me not a disgrace, but an honour …”

Lapienis concluded his speech with the words:

“I would very much hope that the mistakes committed during the period of the Cult of Stalin would not be repeated at the present time. This would only deepen the general crisis of socialism, which would ultimately end in catastrophe.

“Prisons and camps overflowing with prisoners do not greatly enhance our country. It would do society a great deal of good if the authorities concerned themselves not with revenge but with truth.”

The court issued the following sentences: Lapienis, three years in a strict-regime camp and two years of exile; Matulionis, a two-year suspended sentence; Pranskunaite, two years in an ordinary-regime camp.

*

In the official newspaper Tiesa (‘Truth’, 21 August 1977) an article was printed about the trial in which the title LCC Chronicle was replaced by ‘anti-Soviet publication’. The article said:

“The Soviet court is humane . . . Considering that Matulionis understood his errors and promised not to engage in subversive activities, the court decided to convict him only conditionally. …

“Taking into consideration that Pranskunaite is semi-literate [she has primary education, Chronicle] and was drawn into criminal activities, that she regretted the thoughtlessness of her actions at the trial, the court gave Pranskunaite a relatively light sentence, …

“In this connection it is not superfluous to remember that Radio Vatican and other centres of Western propaganda have been intensifying their activities this year …”

In October 1977 Vladas Lapienis was transported to Mordovian Camp 3. Ona Pranskunaite was sent to a camp in the village of Kozlovka (Chuvashia, Volga Okrug).

*

The Arrest of Petkus

On 23 August 1977 Viktoras Petkus (CCE 40.10, CCE 43.12), a member of the Lithuanian Helsinki Group, was arrested in Vilnius.

He was detained at the bus station together with Algirdas Masiulionis. Both were taken to the flat of Petkus for a search. The search was carried out as part of Case No. 38 (the case of Balys Gajauskas, CCE 45.10), and was conducted by Investigator Major Pilelis of the operations squad headed by Major Trakimas and Lieutenant Birvilis. During the search the following items were confiscated:

- two typewriters (Russian and Lithuanian),

- four issues of the samizdat periodical Devas ir Tevine (God and the Motherland; CCE 43.12, CCE 46.20),

- documents of the Lithuanian Helsinki Group Nos. 3-12 (see below),

- “Resolution of the Head Committee of the National Movement of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania” (three copies in Lithuanian; one copy each in Russian, Latvian and Estonian),

- a statement of Mart Niklus to the Lithuanian Helsinki Group (in Russian and Estonian),

- a handwritten text in Latvian signed “Kalnins”,

- a statement of priest Seskevicius to the archbishop.

Besides the typewriters, everything was confiscated from the briefcase of Petkus had with him at the bus station. Both Petkus and Masiulionis were subjected to a body search. Petkus made a protest against the detention and search of Masiulionis as they were not covered by the search warrant. After the search both were taken to the KGB, where Masiulionis was released after interrogation.

Petkus was charged under Article 68 (Lithuanian SSR Criminal Code = Article 70, RSFSR Code). In the post-war years he served a 14-year term of imprisonment, under Article 58 (“Counter-Revolutionary Crimes”) of the old Criminal Code and for escaping from a camp.

The “Resolution” confiscated from Petkus talks of organizational matters: the election of three chairmen of the Committee (their names are not indicated); the transfer of its functions, in the event of it being impossible for the committee to carry on its work, to foreign organizations of Lithuanians, Latvians and Estonians; the election of honorary members, conditional on their agreement (Pyotr Grigorenko, Yury Orlov, Andrei Sakharov and a number of foreign figures); and the publication of a bulletin entitled “Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania”.

At the end of August 1977, a member of the Lithuanian Helsinki Group Ona Lukauskaite-Poškiene sent a statement of protest against the arrest of Petkus to the Lithuanian Procurator. In her statement she also protests against the arrest of Balys Gajauskas. The statement was supported by 81 people.

On 14 November 1977 former political prisoners (Estonians M. Niklus, E. Tarto and E. Udam; and Latvians V. Kalnins, I, Calitis, G. Rode, Ju. Ziemelis and U. Ofkans) addressed Amnesty International with a request for support in the struggle to secure the release of Viktoras Petkus “a Lithuanian fighter for civil and national rights, a member of the Lithuanian group to observe the implementation of the decisions of the Helsinki conference, and one of the chairmen of the Chief Committee of the National Movement of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania”.

(See also “Arrests, Searches, Interrogations” in this issue CCE 47.4).

*

Searches and Interrogations

On 16 and 17 August 1977 an inhabitant of Siauliai, Jonas Petkevičius, was interrogated in Vilnius in the case of Gajauskas.

Lieutenant-Colonel Kazis, who conducted the interrogation in a very rude form, threatened to arrest Petkevičius for communicating ‘slanderous anti-Soviet materials’ to LCC Chronicle. His wife Jadviga Petkevičiene was summoned to appear in Vilnius on 23 August. She was interrogated for two days by the same Kazis, who again shouted, going as far as unprintable abuse. After this Petkevičiene categorically refused to talk to Kazis and on the third day he was replaced by Major Pilelis.

Petkevičiene was accused, amongst other things, of ‘links with Moscow’. At interrogations the couple were ‘advised’ to leave the USSR.

After the search carried out at his flat on 7 February 1977 (CCE 44.22), Petkevičius addressed the authorities many times, in particular the Procurator of Lithuania, with the demand to return to him what had been confiscated. Eventually all his things (camera, the book The Story of Christ and other items) were returned to Petkevičius, except for the composition ‘Vitis’ (a horseman, the Lithuanian coat of arms) and sets of the journal Trimatas for 1938-1939.

*

On 23 August 1977, at the same time as the arrest of Petkus, searches were begun at the homes of Antanas Terleckas [1] and Julius Sasnauskas (CCE 44.22). Both searches were authorised by decree of Investigator Pilelis.

The search at the home of Terleckas lasted more than 24 hours, with a break for the night. The following items were confiscated:

- a typewriter,

- six issues of LCC Chronicle,

- two issues of Ausra, three issues of Laisves Sauklis,

- photocopies of the Russian texts ‘Open letter to the editor of Literary Gazette Chakovsky’ and ‘Documents on the case of Marchenko’,

- a brochure The Case of Kovalyov (Khronika publishers: New York),

- typewritten copies of a large number of articles on socio-political themes,

- the Paris telephone number of Sinyavsky, and

- copies of statements sent by Terleckas to Podgorny and Andropov (CCE 40.10, CCE 43.10).

A part of what was confiscated was dug up on a plot near the house: Terleckas lives on the outskirts of Vilnius. After the search Terleckas was held in prison for three days.

Terleckas refused to give evidence about the documents confiscated from him at the search. KGB officers assured Terleckas that he would not be hindered in finding a job if he gave up his struggle against the Soviet regime, Terleckas stated that he would repeat what he had already written in a letter to Podgorny (CCE 43.12), i.e., that he was not intending to struggle against the Soviet system. Eventually the KGB agreed to this and let Terleckas go.

The wife, daughter and aunt of Terleckas were also summoned to interrogations. They were asked about his acquaintances, his links with Moscow, about an interview given by him to the correspondent of the Financial Times, and about material confiscated from him at the search.

*

The following were confiscated from Julius Sasnauskas: Lithuanian samizdat (including the journal Aidai (Echo), No. 2); several books in Russian — The Diary of Eduard Kuznetsov, Sakharov’s My Country and the World and his Nobel lecture, Peace, Progress and Human Rights; 135 postcards with the composition ‘Vitis’; and a statement by Sasnauskas and three of his comrades about their expulsion from school in 1976 (CCE 42.9 [13], CCE 43.12). On the days following this Sasnauskas was interrogated several times.

In the daytime on 23 August 1977 Major Trakimas of the KGB operations squad and his colleagues detained Jonas Volungevicius at the bus station in Vilnius (where Petkus was arrested an hour later). Volungevicius was taken forcibly to the KGB. There a body search was arranged without a warrant and an interrogation without a procotol, which lasted five hours; nothing was confiscated.

During the interrogation they demanded that Volungevicius stop travelling to Moscow: “For you it is a prohibited city.” When he was let out of the KGB building, several agents followed him calling out (in Russian): “If you run, we’ll pull off your legs! Go home and stay put!” and accompanying these threats with unprintable abuse.

Volungevicius turned to a policeman for protection. One of the agents produced his official identity card: “This is a dangerous criminal,” he said. “Take him to the police station.” The same agent rudely demanded that Volugevicius talk to the policeman in Russian. On 28 August Volungevicius wrote a statement to the Lithuanian Procurator in which he protested against his illegal detention and search and demanded that the KGB officers be brought to trial for threats, insults and slander.

*

In October three members of the Lithuanian Helsinki Group were interrogated.

On 7 October Major Lazarevicius interrogated Eitan Finkelstein. In a statement made by the latter the following day he says:

“Without having explained the specific charge that has been brought against Petkus, the investigator presented me with 19 different materials which he claimed had been confiscated from Petkus during a search and were documents of the Lithuanian Helsinki Group …

“The majority of the questions put to me by the investigator concerned not the case of V. Petkus, but the activities of the Lithuanian Helsinki Group, its other members and myself personally. To all of these questions I refused to give an answer.

“After the interrogation on the case of V. Petkus the same investigator set about interrogating me about the case of Yury Orlov and Alexander Ginzburg. The questions concerned the activity of the Moscow Helsinki Group and its links with the Lithuanian Helsinki Group. I also refused to answer these questions.

“Thus both the materials of the investigation presented to me and the character of the interrogation convinced me that the investigation did not have any convincing proof at its disposal that the activity of V. Petkus in the Lithuanian Helsinki Group was of a slanderous, anti-Soviet nature. On the contrary, all this convinced me that the case of Petkus was in essence the case of the Lithuanian Helsinki Group, and is closely bound up with the cases of other Helsinki Groups in the USSR.

“In connection with this I must state that Viktoras Petkus, as well as the other members of the Lithuanian Helsinki Group, were acting and are acting exclusively within the framework of Soviet legality, and were aspiring and are aspiring to verify as carefully as possible evidence of violations of the principles of the Final Act, which various citizens report to the Group.

As a member of the Group I bear equal responsibility with V. Petkus for the activities of the Lithuanian Helsinki Group and am prepared to stand trial together with him. However, the innocence of V. Petkus as a member of the Lithuanian Helsinki Group is absolutely obvious to me. It is precisely for this reason that I appeal to all the governments of countries which signed the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Helsinki, and to all organizations and individuals fighting for civil rights throughout the world: Do everything in your power not to allow the judicial suppression of Viktoras Petkus!”

*

On 10 October 1977 Father Karolis Garuckas was interrogated in Vilnius. The interrogation lasted seven hours.

On 18 October Investigator Captain Daugalas interrogated Ona Lukauskaite-Poškiene in Siauliai as a witness in the Petkus Case.

The questions concerned the formation of the group, contacts between its members, her acquaintance with Ginzburg and Orlov, with Latvians, with Gajauskas and Volungevicius, and differences of opinion with the people mentioned. Lukauskaite replied that she was not acquainted with any of the people named except for the members of the Lithuanian Group; she had no contacts with Moscow; and she had indeed signed the documents of the Helsinki Lithuanian Group presented to her and confirmed her agreement with their contents.

Lukauskaite repeated her request that Petkus be released. She said that there was no logic in the fact that Venclova, already after the formation of the Group, had been allowed to go abroad, where he was carrying out the mission entrusted to him even more fruitfully, whilst V. Petkus had been deprived of liberty for the same activity. The interrogation lasted about six hours.

In mid-November 1977 searches were carried out at the homes of Erik Udam and Mart Niklus in the case of Petkus (“Arrests, Searches, Interrogations” in this issue CCE 47.4).

More details have become known of the search at the home of Birute Pasiliene near Klaipeda on 22 April 1977 (CCE 45.10). The search was conducted by Major R. Bertulis in the case of Gajauskas (CCE 43.12) and a manuscript headed ‘Draft’ were found in the garden in a beehive. Pasiliene explained that she had found this literature and, without reading it, hidden it from her children. Two typewriters, Russian and Lithuanian, were also confiscated. Pasiliene demands that they be returned.

*

Disturbances in Vilnius

On 7 October 1977, after a football match at the Zalgiris stadium in Vilnius, a crowd of spectators of a few hundred people, basically young people, moved along the streets calling out slogans in honour of their team’s victory and also political slogans: “Down with the Constitution!”, “Freedom for Lithuania!”, “Russians — clear off!”

When the police tried to disperse the procession, skirmishes broke out. Here and there in the procession were Lithuanian (Soviet) flags, held by those who had taken them to welcome their team on the stands. The demonstrators went out on to Lenin Square, where opposite the monument of Lenin is situated the KGB building (a prison is in the cellars, the offices up above). Here the demonstrators continued to call out slogans. According to certain reports the demonstrators broke windows in the KGB building.

On 10 October 1977 events of a similar character developed on a large scale. Troops, mostly soldiers from the Central Asian republics, and many policemen assembled beforehand near the stadium. All 25,000 places in the stadium were filled.

The Zalgiris team were playing against a football team from Smolensk named Iskra. Anti-Russian shouts started during the match: they could be heard by television viewers until the showing of the match was stopped “for technical reasons”. Attempts by the police and voluntary patrols (druzhinniki) to seize those calling out were for the most part unsuccessful: those whom they wanted to seize escaped across the benches with the assistance of those sitting around them. The public left the stadium through ‘corridor’ lined with soldiers. Nevertheless, a procession formed once again. This time, however, 10,000-15,000 people moved into the city centre. Skirmishes with the police broke out continuously, and individual groups overturned police cars.

Near Zalesis bridge (renamed Dzerzhinsky bridge) another 500 people joined those coming from the stadium. Slogans became audible: “Let’s go to the KGB!” “Freedom for political prisoners!”, and frequent cries of “Freedom for Petkus!” Somewhere, in reply to one of the shouts against the Russians, there resounded: “Russians are here with you too!”, “For your freedom and for ours!”

The demonstrators broke through a cordon of police and KGB troops with arms tightly linked on Gediminas Square and moved out on to Lenin Avenue. Only a second cordon on Chernyakhovsky Square (not far from the KGB building) halted them. Agents darted about in the crowd, indicating whom to detain, but often those arrested were wrested back by the crowd. In different places, sometimes from right under the legs of policemen, home-made flags were hoisted noisily and fluttered brightly above the crowd. The demonstrators were dispersed only late at night.

On both 7 and 10 October 1977 the demonstrators tore down posters about the Constitution, the 60th anniversary of the October Revolution, and so on. Some windows with such posters on them were broken. On 11 October all the posters hanging in Lenin Avenue were removed.

*

The number detained and injured is not known. A few policemen landed up in hospital. According to certain reports, in mid-November the procurator’s office of one of the districts of Vilnius (Sovetsky) heard the cases of 17 people arrested on 7 October 1977.

On 12 October 1977 expulsions began from institutes of higher education; some people were expelled only from the Komsomol. An especially large number were expelled from the Engineering-Construction Institute. Repressive measures were also taken in certain enterprises.

An article appeared in the local paper Evening News. It talked only about the escapades of hooligans at the stadium, and the pronouncement of a footballer was published who was indignant at the tactlessness and hooliganism of the fans. All matches in October were cancelled. The match arranged for 4 November was transferred to 8 November 1977. Tickets for this were not publicly on sale, but were distributed at enterprises under the observance of Party committees. There was a huge number of policemen at the stadium on 8 November, some of the police buses having Minsk number-plates.

In Telšiai on the night of 7 November 1977 inscriptions appeared on the streets (mostly on posters for the 60th anniversary of the October Revolution): “Russians, get out of Zemaitija!” (a region of Lithuania), etc. In Salcininkai. on the fourth floor of the building of the town soviet executive committee was written in large letters; “Long live a Free Lithuania”, “Down with the Russians!”

*

LCC Chronicle (29) reports continuing repression of priests and believers.

On 27 July 1977, when 25 children had assembled in the church of Vidulke in preparation for their first communion, the chairman of the local soviet, a policeman and four teachers entered the church and began to take the children’s names. A document was drawn up against the incumbent of the church A. Svarinskas.

The incumbent of the church in Kirdeikiai, P. Krazauskas, called on his parishioners to tidy up the cemetery and decorate the graves. The local authorities accused the priest of attempting to ravage the graves of Soviet activists and demanded a written explanation from him.

A priest from Kibartai, S. Tamkevičius, was unable to obtain permission to leave for a neighbouring district to help the incumbent there — the chairman of the soviet executive committee referred him to the head of police, the latter to a KGB representative, and so on.

In June 1977 Commissioner Tumenas of the Council for Religious Affairs visited Zaljoi, a small population centre, and promised the local inhabitants that he would look favourably on their request to open a local church. After his departure many parishioners were subjected to various administrative punishments, and a mill was built in the church.

*

LCC Chronicle (29) publishes the complaint that V. Jaugelis (CCE 34.6, CCE 36.7) sent to the UN Committee of Human Rights (copy to the Republican and All-union Procurators) about an incident which occurred on 23 June 1976.

Jaugelis was then detained on a street in the town of Raseiniai, searched without any documents being shown, and had the book Christianity in the World taken away from him. Jaugelis has been trying to have the book returned.

*

This summer Father Karolis Garuckas received a letter from ‘Lithuanians’ who reproached him that Eitan Finkelstein is a member of the Lithuanian Helsinki Group and that the Lithuanian Group maintains contact with Moscow dissidents, the majority of whom are of Jewish descent.

*

On 18 October 1977 late in the evening, when Algirdas Masiulionis and Andrius Tuckus were walking through one of the squares in Vilnius, some people stopped them, called a police patrol and said that they and two others who had hidden themselves were behaving like hooligans.

Masiulionis and Tuckus were taken to the police station and a written explanation of what they were doing in the square was demanded from them. The policeman conducting the inquiry gave Tuckus, who did not want to write and speak in Russian, a strong blow with his shoe in the lower part of his back; continuing to beat him, they dragged him off to a cell. Masiulionis, although he wrote an explanation, but evidently not what was required, was also beaten up. They were held at the police station from 12 midnight until 4 am.

*

Vytautas Boguszes, Algirdas Masiulionis, Julius Sasnauskas and Andrius Tuckus wrote a statement on 8 November 1977 to Barkauskas, chairman of the Presidium of the Lithuanian Supreme Soviet (copy to the military commissar of Lithuania), about being called up for military service.

In spring 1976, they wrote, they were “expelled from the Vienuolis secondary school in Vilnius for their religious and nationalist convictions” (CCE 42.9 [13], CCE 43.12). Since then they have heard on several occasions from the KGB and the police that their path to institutes of higher education is closed, that they will be taken into the army and sent to Spitzbergen or to the Chinese border. Two who signed the statement tried nevertheless to enter an institute of higher education. Masiulionis did not pass the entrance examinations, but Tuckus, although he attained the pass mark, was all the same not accepted, in accordance with ‘information from above’ as the rector of Vilnius State University explained frankly. On graduating from evening school, they were all given testimonials with the formula: “unhealthy views”, “not free from religious prejudices”, etc. The statement says further (quoted in translation):

“We became Soviet citizens not of our own free will, but only because we were born in Lithuania.

“The Soviet press maintains that service in the Soviet army is a matter of honour and inspires every youth with a feeling of pride for the trust shown in him. We do not feel anything of the sort because both the KGB and the police have assured us that for us the army will be a punishment for our beliefs. Despite this we do not refuse to serve in the army. We only ask that we be left to serve in Lithuania …

“The local writer Ju. Baltusis proclaims with pride that today Lithuania is ‘free and independent’. Citizens of an independent State, as is clear to everyone, should serve in their own country.”

*

The Lithuanian Helsinki Group

DOCUMENTS

Below is a survey of the documents published by the Group, since its formation in November 1976 (CCE 43.12) up until July 1977. All the documents were signed by Father Karolis Garuckas, Eitan Finkelstein, Ona Lukauskaite, Viktoras Petkus and Tomas Venclova.

CCE 43.12 has already presented the contents of Document No. 1 (On two Lithuanian Catholic bishops), Document No. 2 (On the ‘Statute on religious associations’), and several other statements of the Group.

No. 3 (23 Dec 76) An account of the fate of Mart Niklus (CCE 42.3, CCE 43.12).

No. 4 (25 Feb 77) Maria Jurgutiene (with her daughter, who is a minor) is not allowed to leave to join her husband for permanent residence in the USA (CCE 36.9 [3], CCE 44.24). Vale Belupatraviciene (CCE 45.15) is not allowed to leave to join her father for permanent residence in West Germany.

No. 5 (28 Feb 77) Report on a search carried out at the home of Genrikas Jaskunas on 22 December 1976, after which Jaskunas was arrested (CCE 44.22).

No. 6 (19 March 77) Tells of the appeal of 49 German families, now living in the Radviliski district of Lithuania. The Germans repudiate their Soviet citizenship and ask to be allowed to leave for their historic homeland, West Germany.

No. 7 (26 May 77) The story of Erik Udam from Tallinn, to whom the KGB proposed in April this year that he organize a group of dissidents under his control, with links with the USA (CCE 46.17 [12]).

No. 8 (2 June 77) Tells of the fate of Pentecostalist Victor Vasilyev living in Vilnius, who is constantly subjected to persecution. The Vasilyevs ask to be allowed to go abroad.

No. 9 (14 June 77) On the situation of political prisoners who have been released.

The majority (there are a few exceptions) of those who have served 15-year and 25-year sentences are not allowed to return to Lithuania.

Some of those released come to Lithuania of their own accord and refuse to go beyond its borders. Sometimes they manage to “prove more stubborn” than the KGB and the police and remain in Lithuania. Even in these instances, however, it costs the authorities nothing to take away a passport, de-register a person, and convict him for violating the residence regulations.

No. 10 (16 June 77) A report on the arrest of Balys Gajauskas (20 April 1977).

Brief information about his first arrest in 1948 and the trial which sentenced him under Article 58 (counter-revolutionary crimes) to 25 years of camps. Also reports on the searches linked to the Gajauskas case (CCE 45.10) at the homes of Birute Pasiliene, Leonardas Stavkis and Ona Grigaliunaite.

No. 11 (26 June 77) Estonian Enn Tarto (b. 1938), who has twice been convicted (1956 and 1962) under political articles and has served nine years, reports that up till now the KGB has not left him in peace (has been interrogated several times, particularly “because of his links with Gorbanevskaya”). This year they have already tried to set fire to his house four times.

No. 12 (1 July 77) Tells of the fate of Algirdas Zipre (CCE 32.12, CCE 34.9).

In October 1973 Zipre was transferred to a camp ‘loony bin’ (written thus in the text) located in Mordovian Camp 3. According to information gathered by the authors of the document, the conditions there are much worse than in the camp itself. Windows are always tightly closed, no links with the outside world are permitted, there are no walks, prisoners are beaten, and are given strong doses of unmarked medicines.

Algirdas Zipre has been beaten twice. On two occasions he was taken to Moscow, to the Serbsky Institute. This year he has been taken off to an unknown destination.

*

A Statement on the Contemporary Situation in Lithuania (8 pp., 7 July 1977).

The statement basically concerns the following issues:

- The situation of Lithuanians exiled from the republic in the prewar and first post-war years.

Many Lithuanians still remain in exile “without trial and sentence” and it lists some of them: Stepas Bubulas, Kostas Buknis, Antanas Deksnis, Alfonsas Gaidis, Algirdas Gasiunas, Robertas Indrikas, Antanas Jankauskas, Jonas Karalius, Leonas Lebeda, Kostas Leksas, Juozas Mikailionis, Aleksas Musteika, Petras Paltarokas, Povilas Peciulaitis, Vytautas Petrusaitis, Albinas Rasitinis, Vincas Seliokas, Vytautas Slapsinskas, Jonas Sarkanas, Benius Trakimas and Vladas Vaitekunas. - The state of the Lithuanian language.

The number of Russians living in Lithuania has increased five-fold in the last thirty years; there are particularly large numbers of Russians in Vilnius and Klaipeda. - The situation of Lithuanians in Latvia and Belorussia.

In Latvia, on the eve of the war there were 18 Lithuanian schools. Now not a single one remains. The situation is almost the same in Belorussia where Lithuanian schools have long been closed, churches are being closed, and the authorities are hindering Lithuanians from inviting priests from Lithuania to come to them. - The situation of Poles in Lithuania.

According to the facts of the last census in Lithuania there are almost as many Poles living there as Russians. However, it is impossible to find notices in Polish anywhere; the Poles do not have their own theatre, there is no possibility of receiving a higher education in Polish. (There is only one Polish group in the Pedagogical Institute.) - The situation of other national minorities in Lithuania.

There is now not a single Jewish school in the republic, yet before the war there were 122 primary, three incomplete secondary (pre-grammar school) and 14 secondary schools (grammar).

According to the 1970 census there are 16,000 Jews in Vilnius, and 4,000 in Kaunas.

There are 24,000 Belorussians in Vilnius, but there is not a single Belorussian school in the city, and not a single Belorussian paper. Tatars and Karaim are in the same situation.

In the final-year classes of Lithuanian schools four hours are devoted each week to the Lithuanian language and five to Russian.

It is impossible to obtain almost any book issued before 1940: even The USSR Through Our Eyes, a work by Paleckis, former chair of the Presidium of the Lithuanian Supreme Soviet, now chairman of the USSR Council of Nationalities, is kept in a secret store-room. Many classical books, historical and economic works, have been stolen from readers. At searches, pre-war publications are often taken away. In the first post-war years many archives and libraries were destroyed. - Many historical monuments are falling into disrepair.

The Catholic Church of St. Kazimir (1604) in Vilnius, for example, was for ten years a warehouse for wine bottles.

In conclusion the authors of the Statement point out that they have dealt with only a small part of the problem. They ask the governments of countries which signed the Helsinki Declaration (in August 1975) to note that agreements which are not implemented, or implemented only on one side, have no meaning and are a deception.

==================================

NOTES

- On Terleckas, see CCE 38.3, CCE 40.10, CCE 43.12 and Name Index.

↩︎

==========================