[1] Arrest of Tatyana Osipova

[2] MHG receives a warning

[3] Trial of Victor Nekipelov

*

1. The Arrest of Tatyana Osipova.

On 27 May 1980, KGB Lieutenant Kruglov with three KGB officers (Belov, Topolyov and Gurzhos) searched the home of Moscow Helsinki Group members Tatyana Osipova (b. 1949) and her husband Ivan Kovalyov (b. 1954) in connection with her Case, 35.

A large number of Moscow Helsinki Group documents were confiscated, as well as various issues of the Chronicle (several copies of CCE 54), a freshly typed ‘edition’ of Bulletin No. 8 of the Disabled Action Group (CCE 56.25), numerous documents and materials containing information, letters in defence of arrested people (several copies of letters in defence of Alexander Lavut and a rough draft of Ivan Kovalyov’s letter about him), statements by various persons to government institutions and to the Moscow Helsinki Group, replies from official institutions, a list of political prisoners, a list of Pentecostalists trying to emigrate, and Ivan Kovalyov’s letters (in defence of his imprisoned father Sergei Kovalyov and about the detention of his own wife) see CCE 56.21.

Among other things the following were confiscated:

- four typewriters;

- two small tape-recorders and cassettes (mostly unrecorded);

- the issue of Roman-Gazeta [1] in which “A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” [1963] was printed; and a photocopy of Velimir Khlebnikov’s Children of the Otter [1913] (neither book was taken during the previous search);

- several samizdat works including:

“Six Documents” by Yury Shikhanovich (CCE 55.11 [2]), “Sergei Kovalyov: The Story of a Hunger-Strike” by Ivan Kovalyov (CCE 54.13-1 [3.3]), and a book about psychiatric hospitals by Alexander Shatravka (CCE 51.11), “If You Have the Freedom Disease, or A Report from a Cannibal’s Stomach”.

Fifty-two photographs were confiscated.

They include photos of Lefortovo and Butyrka Prisons, various psychiatric hospitals, and Perm Camp No. 36. Also photos of individuals: Vyacheslav Bakhmin and Father Dmitry Dudko (“persons against whom criminal proceedings have been instituted”), Andrei Sakharov (“regarding whom administrative measures have been taken”), and a photo of Osipova herself. During the previous search on 10 April 1980 (CCE 56.3), only three photos of Bakhmin were confiscated. Other photos of ‘prosecuted’ persons, however, e.g., Tatyana Velikanova, Sergei Kovalyov and Alexander Lavut, were left behind.

During the search, Ivan Kovalyov was permitted to copy out his address book, but certain pages of the new book on which he wrote the phone numbers of foreign journalists and addresses abroad were taken from him. During the search Osipova and Kovalyov were visited by Alexander Ebel, a relative of German refuseniks who demonstrated in Red Square on 31 March 1980 (CCE 56.20). The KGB search party confiscated an address book and a copy of a letter to relatives in West Germany from Ebel.

In their comments on the search record, Osipova and Kovalyov pointed out

“…The material confiscated is not slanderous in nature.

“It was confiscated with the aim of putting a stop to the circulation of information on violations of human rights in the USSR, which is yet another confirmation of the truthfulness of the material.”

*

After the search, Osipova was taken to Lieutenant-Colonel B.I. Chechetkin, Head of the USSR KGB’s Investigations Department, to be interrogated.

There she was arrested and charged under Article 70 (RSFSR Criminal Code). The investigation is being conducted by the KGB; in addition to Chechetkin, the investigation team includes Lieutenant-Colonel V.A. Skalov and Lieutenant-Colonel Yu.I. Suchkov, Senior Investigators for Especially Important Cases, Investigator Saushkin (//CCE 46-8, 51-3) and Major Gubinsky (//CCE 48).

*

On 4 June 1980 and in early July, in Moscow, Saushkin twice interrogated Victor Chamovskikh from Kerch (CCE 33.6-3 [16], CCE 40.15 [18] and CCE 45.11-3) in connection with Osipova’s case. He wanted to know when and where Chamovskikh had made Osipova’s acquaintance and what he knew about her activities in the Helsinki Group.

On 17 June 1980, Skalov interrogated E. Sokolinsky, Osipova’s immediate superior at the Central Geophysical Expedition. Sokolinsky described Osipova as a good worker and said that he did not see her outside working hours. He had asked Osipova, he said, about her activities in the Moscow Helsinki Group (he had learnt she was a Group member from a Voice of America broadcast), but she declined to answer, saying that she considered her activities to be beneficial to our State.

Asked about Osipova’s relations with Alexander Lavut and other workers in the Central Geophysical Expedition, Sokolinsky replied that Osipova had no close friends. She was on good terms with Sokolinsky’s wife, but did not discuss her activities with her or with anybody else. She was on good terms with Lavut, but the witness knew nothing about their meetings outside working hours.

In June 1980, Osipova’s mother, stepfather and grandmother were interrogated. Her grandmother was visited at home. Her visitors complained to her about Osipova’s ‘stubborn character’.

*

Boris Mordvinov, who shares a communal flat with Osipova and Kovalyov (three families live there), once boasted proudly to Osipova that he was collaborating with “our brave Chekists”. Osipova and Kovalyov have reason to believe that he reads their post and sometimes keeps their letters; he goes into their room while they are out; and he exchanges information about them with the agencies of State Security.

On the day of Osipova’s arrest, 27 May 1980, Mordvinov went out earlier than usual to clean his shoes in the stairwell, leaving the front door of the building open. Osipova guessed that they would come straight away for a search. A few minutes later, KGB officers were already in their room. Now that Osipova has been arrested, when Mordvinov answers the doorbell, he sometimes says that Kovalyov will not be there much longer.

Boris Ivanovich Mordvinov is about 80 years old. He used to work as a personnel officer; in his retirement he works as a Party activist.

*

On 28 May 1980, the MOSCOW HELSINKI GROUP adopted Document 133, “The Arrest of Tatyana Osipova”. The document contains biographical information about Osipova and describes her civic activities:

“… Tatyana Osipova has a wide range of interests, which are not limited to civic problems only; she is acutely aware, however, that no activity of full value is possible in a society without civic freedoms.

“Tatyana Osipova’s civic activities have given rise to continual persecution by the authorities. She has been subjected several times to searches and arrests; in January this year she spent 25 days in jail; for 21 days she maintained a hunger-strike in protest.

“A totally innocent person, she now faces the threat of a cruel punishment: many years imprisonment in a camp.

“All Tatyana Osipova’s activities have been aimed at the genuine implementation of the Helsinki Agreement in our country: her arrest is a crude violation of that Agreement.”

On 30 May 1980, Ivan Kovalyov published an essay “About My Tanya”.

He briefly describes the ‘pre-arrest’ search:

“… But it was already clear to us: after the third search in eight months; with so many of our friends and close ones arrested and detained over the same period; and now, there’s a ‘criminal case’ against Tanya. It means she will be arrested.

“Our turn has come to embrace for the last time and tell one another: ‘I love you to distraction, there is no one nearer and dearer to me than you.’ Let those inhuman creatures crowd around us: we have nothing to be shy about in front of them! Yet one of ‘them’ butts in, ordering us to sit apart and not to ‘talk to each other’. We laugh, and he orders that a note be made in the record that we have been disobedient.

“Well, then … they take Tanya away, as if they are stealing her. They say it is for interrogation. We want to go together, but they put her in the car and push me away. Nearby are the sneering faces of the undercover agents — apparently, they had surrounded the building while the search was on. There is a nod from behind the car window. They’ve gone. That was our farewell.”

*

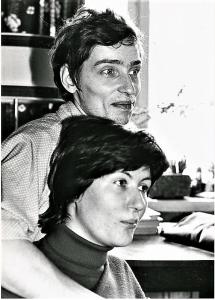

Ivan S. Kovalyov and Tatyana Osipova (1970s)

*

The trial of Sinyavsky and Daniel, where thoughts and words were on trial (writes the author), shook the belief of Tatyana Osipova, then a Komsomol member, that ours was the most just society in the world. And then there was the invasion of Czechoslovakia, which made her realize that “her way of thinking did not correspond to what was prescribed”:

“… She wanted to act.

“For Tanya, action means openly telling the truth about violations of human rights in her country. The only ‘ulterior motive’ behind this activity is the desire to live in accord with one’s own ideals and convictions.

“It began with signing documents, then there was Pushkin Square [2], and she joined the Helsinki Group. Tanya defends those who’ve been arrested and speaks out for the rights of prisoners. She defends the right of believers to their faith and the right of Germans, Jews and Crimean Tatars to their homeland. She does everything in her power to make reliable information about the struggle for human rights in our country, and about violations of these rights, available to everyone.

“And in every search of our flat they take away copies of the Chronicle, Group documents, and informational notes and materials. In violation of the law, they take everything containing the truth about the struggle for human rights and about persecution for this struggle. The truth which the authorities try to conceal.

“Hardly a day passes without visitors coming to our room.

“Dozens of people, from many towns and cities. And Tanya found time for each of them, a word of sympathy and support. The telephone rang continually, reports of searches, detention, and arrests.

“Normally, we had hardly any time to ourselves. Yet we could not live any other way. Especially when the arrests of our friends came thick and fast, one after the other: Velikanova, Nekipelov, Bakhmin, Landa, Ternovsky and finally our closest friend, Alexander Pavlovich LAVUT.

“…Tanya was arrested, not for committing a crime, but because she dared and was able to speak the truth, to help prisoners and their families and all the people who came to us. Because of the respect she has earned.

“This is considered an ‘especially dangerous crime against the State’. Now the investigation will rummage through our papers, collect ‘evidence’ and look for ‘proof’ that Tanya lied, slandered, defamed, undermined the State’s prestige. As a result, real facts which are unpalatable to the authorities will become ‘slanderous fabrications’, and their publication ‘an attempt to undermine State prestige’.

“It is shameful to arrest people for kindness, compassion and sincerity.

“IT IS DOUBLY SHAMEFUL TO ARREST A WOMAN.

“I call upon all who cherish freedom, outspokenness, mercy and justice, all who feel respect for women, to come to Tanya’s defence.”

A collective letter entitled “Reprisals for Honesty” (10 June 1980, 31 signatures) reads in part:

“All her ‘activities’ arise from natural human qualities: honesty, kindness, mercy and compassion. And from the remarkable firmness of her moral position, which is in essence extremely simple: every person is responsible for what happens around him. Knowing that someone else is in trouble, one cannot refrain from trying to help him. Tanya ‘only’ does what she cannot help but do. Her moral duty compels her.

“These moral qualities of Tanya’s were very obvious to everyone who knew her even slightly.

“Evidently this is why they kept coming to her for advice, for a kind word, often just to say what was on their mind. She would put everything else off to listen, take notes and help them. Then tens of thousands would read in samizdat and hear on the radio about persecution of dissidents in the USSR and about the authorities’ violations of their own laws. Again and again people come: Tanya listens and takes notes.

“The letter is available for signing until the investigation of Osipova’s case is over.”

On 19 June 1980, Ivan Kovalyov wrote to the Parisian “Committee to Defend Soviet Women”:

“… I ask your committee to use all its influence to obtain the release of Tatyana Osipova.

“In my name and in Tanya’s name, I ask you also to work for the release of certain other women: Tatyana Velikanova, Olga Matusevich and Oksana Meshko, who are now under investigation; Malva Landa and Ida Nudel, who have already been convicted and are now serving terms in exile.

“I ask you to speak out for anyone else in our country who may be subjected to repression for their civic activities and who is in danger now.”

On 23 June 1980, Osipova’s colleagues at the Central Geophysical Expedition (six signatures) sent an Open Letter in her defence to the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet, to the editors of Pravda and to the USSR Procurator-General. Their letter contains a demand for Osipova’s release.

*

On 4 July 1980 (see “The Right to Leave”, CCE 57.18), KGB Lieutenant-Colonel Suchkov interrogated Moscow Helsinki Group member Yury Yarym-Agayev, ostensibly in connection with Osipova’s case.

At the beginning of the interrogation Suchkov assured Yarym-Agayev that there would be no link between his emigration and his behaviour under interrogation. The questions chiefly concerned the Moscow Helsinki Group, its membership, structure and activities. At the end of the interrogation Suchkov asked Yarym-Agayev to come for another interrogation the following day. When on 5 July 1980, Yarym-Agayev failed to turn up, Karatayev woke him with a phone call and asked why he had not appeared. Yarym-Agayev replied that he was exhausted from the previous day and would not come to be interrogated that day. They agreed to hold the interrogation on 6 July (a Sunday).

At the second interrogation the main question was whether Group members knew that their documents were being used in the West for anti-Soviet purposes.

*

2. A Warning to the Group.

On 30 May 1980, Yarym-Agayev received a “warning in accordance with the Decree” (25 December 1972). The ‘Warning record’ stated:

“The USSR KGB warns citizen Yu.N. Yarym-Agayev that, as a member of a hostile grouping that calls itself the ‘Group to Assist the Implementation of the Helsinki Agreements in the USSR’, he is continually involved in the circulation of anti-Soviet and slanderous fabrications: he maintains constant contact with foreign correspondents and representatives of embassies of capitalist countries, and holds so-called ‘press conferences’, where information is circulated which undermines the prestige of the Soviet State.

“These actions constitute an infringement of Soviet legislation and are liable to criminal prosecution.”

*

On 9 June 1980 the MOSCOW HELSINKI GROUP adopted Document 135:

“The authorities have declared the ‘Moscow Group to Assist the Implementation of the Helsinki Agreements’ a hostile grouping. In the past, the authorities have avoided such definitions or references to the Group, even in the indictments and during the trials of Group members.

“The description of the whole Group as a hostile grouping openly shows how the authorities are ignoring the Helsinki Agreement, which includes a call to individuals and associations to assist its implementation in all ways possible.”

*

3. The Trial of Victor Nekipelov.

From 11 to 13 June 1980, an assizes session of the Vladimir Region Court held in Kameshkovo (Vladimir Region), heard the case of Moscow Helsinki Group member Victor Nekipelov.

Arrested on 7 December 1979 (CCE 55.2-4), he was charged under Article 70 (RSFSR Criminal Code).

The Judge was N.N. Kolosov, Chairman of the Regional Court; the prosecutor was Deputy Regional Procurator Salnov. There was no defence counsel (CCE 56.3).

*

TRIAL

Nekipelov’s relatives were not told when the trial would begin.

On 4 June, his wife Nina Komarova asked Volkova, secretary of the Regional Court, about the date of her husband’s trial. She knew nothing about it, Volkova replied (on 2 June a preparatory meeting of the court had set the date of the trial). On 5 June 1980, the Vice-Chairman of the Regional Court also “knew nothing.”

On 11 June 1980, Komarova travelled from Kameshkovo to Vladimir to deliver her regular parcel to her husband, who was being held in Vladimir Prison. In the Regional Court she learned by chance that a ‘special case’ was being heard in Kameshkovo, and that the court officials were being sent there for three days.

Komarova returned to Kameshkovo, where the court session had already begun. That day she did not manage to get into the courtroom.

A few minutes after she made her way into the court building, the ‘special audience’ thronged out of the room where the case was being heard, and Komarova learned that although it was still early in the day (about 1.00 pm), a recess had been declared until the next day.

*

Nekipelov’s son Sergei (CCE 55.9 [4], CCE 56.3) was summoned on 11 June 1980 to an interrogation at the Procurator’s Office; Sergei’s wife, A. Podyapolskaya, was asked to go to the University on an academic matter.

However, they both went to Kameshkovo, without knowing yet that the trial had begun. They did not manage to attend the first session.

*

THE INDICTMENT

On the first day of the proceedings the indictment was read out.

Nekipelov was charged with producing and circulating the following (many are referred to briefly in CCE’s “Samizdat updates”):

- seven poems from his collection of poems Anaesthesia [3]. The collection contains about one hundred poems;

- the articles “Why Didn’t I Sign the Stockholm Appeal?”, “Stalin on the Windscreen” (CCE 51.21 [13]): “How they Searched us” (CCE 46.20), “Three Years in the Camps” (about Mikhail Kukobaka), “In Defence of Little-Known Prisoners”, “When there is no Contest between the Parties” (CCE 53.30-1 [6]), “The Faculty of Democracy” (CCE 54.24). “Erased from the Facade” (CCE 52.13);

- ‘Oprichnina-77’ and “Oprichnina-78” [4];

- two Moscow Helsinki Group documents — 85: “The Violation of Socio-Economic Human Rights in the USSR. The Right to Work” and 98: “Political Trials of Manual Workers in the USSR”;

- letters in defence of Yevgeny Buzinnikov (CCE 51.3) and Eduard Kuleshov (CCE 52.4.2); the letter “To Find A Man” (CCE 48.24);

- a statement renouncing his Soviet citizenship (CCE 46.9); the statement “For Considerations of Secrecy” (CCE 51.16);

- a translation from Ukrainian of The Cataract, a novella by Mikhaylo Osadchy (CCE 48.10, CCE 52.5-1).

In addition, he was charged with “possession with the intent to circulate”: Solzhenitsyn’s article “Live Not By Lies”; Roy Medvedev’s article “On Volume Three of The Gulag Archipelago”; a review of the book On Bureaucracy; a letter from Melnikov to Tatyana Khodorovich; and the song “We Renounce the Red World …“ (Nekipelov heard it in the camps and wrote it down from memory).

*

Nekipelov refused to take part in the court proceedings until his wife was admitted. On 12 June 1980, there was ‘no room’ for Nekipelov’s friends in the courtroom.

In front of the court building there were many KGB officers from three cities: Vladimir, Kovrov (Vladimir Region) and Moscow. They included Zakharov, the officer who carried out the search at Osipova and Kovalyov’s home on 11 October 1979 (CCE 54.2-1) and detained them on 10 December 1979 (CCE 55.9).

Ivan Kovalyov, Ksenia Velikanova, Yury Kashkov and Vladimir Tyulkov (CCE 46.6, CCE 47.14 [11], CCE 56.6) wrote and submitted a statement to the court commandant: the trial was being held in violation of the law on the publicity of legal proceedings, they pointed out. People wishing to attend the trial were admitted selectively. They also insisted in advance on their right to attend the reading of the judgment, since the reading must be open to the public: allusions then to “lack of space” would be groundless.

As Fuat Ablyamitov was leaving for Moscow, his documents (see “The Case of Lavut”, CCE 57.7) were checked. Yury Kashkov was detained (CCE 57.23).

*

Nekipelov’s son Sergei and his wife A. Podyapolskaya were admitted to the courtroom.

Nekipelov’s wife Nina Komarova was told in the yard of the court building ten minutes before the beginning of the trial that she was being called as a witness. On Nekipelov’s petition she was first to be questioned. After refusing to answer questions on how the article “About Our Searches” was written and sent abroad, and who translated Osadchy’s The Cataract into Russian, Komarova stated that her husband had availed himself of the rights and freedoms guaranteed in the Constitution, and therefore his indictment under Article 70 (RSFSR Criminal Code) was unconstitutional.

The Judge interrupted the witness and released her from further questioning.

Sergei Nekipelov also asked to be questioned as a witness. His father seconded his request, but the court refused them.

When Sergei attempted to photograph his father from the courtroom, he was taken out and his film exposed. He was asked who had given him the camera and who was standing by the court building. He refused to talk and returned to the courtroom. At this point someone promised to throw him off the staircase and break his head open.

*

WITNESSES

From the questioning of the witnesses it was ascertained that:

1. Victor Nekipelov was a good worker.

He was not a trade union member, he did not take part in community work, nor did he participate in elections. Nekipelov did not sign the 1950 Stockholm Appeal and would not plant flowers, saying that he was not hired to do this. In addition, people came to see him and he received many letters, particularly from abroad.

This was the testimony of witnesses from his place of work: Head Doctor of the District Hospital K.N. Maiorov, laboratory director K.E. Yegereva and laboratory assistant M.M. Dranitsyna.

*

EMIGRATION

2. Victor Nekipelov had reached a point, he himself said, where he was in basic disagreement with the system and could no longer live in this country.

He threw his passport [ID document] on the desk of the passport office head and lived for two years without a passport. (In fact, Nekipelov sent his passport to the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet (CCE 46.9 [2], CCE 47.8-1 [2]) and refused to pick it up at the Kameshkovo Passport Office; he had nothing to throw “on the desk”).

It was not at all clear why Nekipelov should wish to leave the USSR, as there were very few people who wished to do so; three or four each year. (Witnesses: Shaidrov, Head of the Vladimir Region Passport Office, and L.F. Shibayeva, Head of the Kameshkovo Passport Office.)

*

PRO-CHINESE

3. During a search of Nekipelov’s home in 1973 many pro-Chinese documents [5], containing a call to overthrow the Soviet system, had been confiscated. In a search of Nekipelov’s home in 1978 a text was found beginning with the words “We Renounce the Red World”. (Witness Gavrilov, a local policeman.)

*

IN THE CAMPS (4-5)

4. Prisoners in the camps were well taken care of.

They worked eight hours a day, safety regulations were observed, and there were days off.

All the convicts worked well, but some refused to work. The food norms were observed; those who were ill were given food according to doctors’ instructions. The prisoners got eight hours sleep, even more; it was never restricted. (Judge: “It should be stricter.” Witness: “That’s the law.”)

There had been cases of prisoners dying (CCE 47.9-1). One prisoner suffering from high blood pressure, for example, had died as a result of taking too many tablets. Pekharev died in hospital of a perforated ulcer; he tore out his own stitches. Volobuyev, a tubercular patient, died because he would not take any medicine or allow anyone to give him injections, and he had done himself bodily harm.

To Nekipelov’s questions the witness replied that he knew nothing about the beating of Fyodorov and Romanyuk, or about the two-month long hunger-strike by prisoners because of the frequent beatings and the high mortality rate. “The convicts frequently wrote complaints”, he said. “about harmful working conditions.” (Here the Judge commented that they were ‘greenhouse’ conditions. Witness Nadezhkin, former head of the medical unit, Mordovian Camp No. 1.)

5. There was no tyranny in the camp.

There was a hospital with ten beds and an out-patient reception. A solarium had been set up in the camp (‘a warm sunny glade’) where the convicts played football and volleyball. They lived better than the witness, he said, inasmuch as he did not always eat lunch, while they had three meals a day. Danilo Shumuk was indeed very thin, but this was due to his ‘asthenic’ [debilitated] constitution. (Witness I. V. Petrov, a medical officer, Perm Camp 36.)

*

6.

After reading two letters from Victor Nekipelov to her son Oleg Solovyov (CCE 52.15-1, CCE 53.30-1 [15], CCE 54.22 [6]), one witness had written, asking him to leave her son alone. She informed the KGB about his letters. (Witness A.D. Solovyova of Zheleznovodsk did not attend the trial; her testimony was read out.)

7. Nekipelov asked for writing-paper.

But it was not sold to him on the instructions of Yakovleva, the bookshop manager. He bought exercise books, ballpoint pen refills, pens and toys. (Witnesses V.A. Barabanova and G.A. Vorobyova, salesgirls in the Kulttovar shop.)

*

8. Nekipelov had reviewed a witness’s manuscripts.

He had not shared the man’s opinions and views; his beliefs were his own business. (Witness N. D. Tolmachev (CCE 54.24 [4].)

*

PUBLICATION ABROAD

9. Nekipelov had provided his article “Erased from the Facade” (CCE 52.13)

for publication in the Bulletin of the Disabled Action Group.

It was not known how the article ended up in Paris, in the émigré newspaper Russkaya Mysl. (Witness Olga F. Zaitseva, CCE 57.5.) The Judge told Zaitseva that if her husband Valery Fefyolov (same section) continued to engage in ‘slanderous activities’ he would “make things worse for himself”.

*

25TH PARTY CONGRESS

10. Nekipelov’s younger son Yevgeny, then a schoolboy in his 3rd year, said at a meeting that

People met and talked at the 25th Party Congress (24 February-5 March 1976), decided nothing and went away again.

In a talk with the headmaster of the school Victor Nekipelov said he was not going to explain anything to his son and refused to assist the school in educating him.

(Witness I.S. Bylov, a teacher and former headmaster of the school, did not attend the trial; his testimony was read out on the petition of Nekipelov, who said that on the basis of Bylov’s statement a file on his own son Yevgeny had been opened. Nekipelov also stated that a file had been opened on his eldest son Sergei, while a case against N. Komarova had been separated for investigation by KGB agencies.)

*

NEKIPELOV SPEAKS

After the witnesses had been questioned, Nekipelov was given the opportunity of commenting on their testimonies and on the episodes in the indictment.

Since 1976, Nekipelov said, he had been trying to emigrate and had been refused permission on at least four different grounds. One of the main documents with which he was charged was a “Statement of Renunciation”. Described by the investigation as libellous, it mentions the oppression suffered by his father and also that Nekipelov called the entry ‘Harbin (China)’ as his “Place of Birth” a ‘black mark’ against him.

HARBIN

The investigators asserted that his father had not been subjected to any acts of repression. Nekipelov was born in Harbin (northern China) but it had not prevented him from graduating from three Soviet educational establishments.

Nekipelov explained that in 1941 his father was exiled from Noginsk (Moscow Region) to Ishim in west Siberia because he had formerly lived abroad. He himself had applied to several institutions of higher education and passed all the exams with excellent marks, but not been accepted. Everywhere, in all documents, the word ‘Harbin’ had been underlined in red.

It was only by chance that he managed to enter the Omsk Military Medical School and the Kharkov Pharmaceutical Institute. He had been accepted at the Gorky Literary Institute (Moscow) because the Cult of Stalin was then beginning to be exposed.

*

MHG

The main part of the indictment, Nekipelov said, concerned his involvement in the Moscow Helsinki Group. He could not understand why he was charged with only two of the 84 group documents in the case file. Nekipelov petitioned the court to expand the indictment by including a further 48 documents that carried his signature [6].

This petition was turned down. Nekipelov also petitioned the court to read out the additional documents. The court refused this too.

Nekipelov requested the court to call 21 additional witnesses, co-authors of the documents with which he was charged and people about whom the documents were written. This petition was not granted either.

*

Nikepelov’s next petition was for the confiscated personal documents be returned to him: e.g., a certificate attesting to his being elected an honorary member of the American PEN-Club, that was taken from his mail after his arrest. The Procurator supported this petition; however, the court decided to resolve the matter after the trial was concluded.

Nekipelov petitioned the court to return the private letters which had arrived after his correspondence became subject to systematic confiscation, and to return certain literary materials which the investigation had resolved to destroy. The court resolved to forward this petition to the KGB for consideration.

*

On the last day of the trial Nekipelov continued to offer explanations in response to the questioning of the witnesses and episodes in the indictment.

He divided the indictment into three parts. The first consisted of his literary activities; the second, of his defence of human rights; and the third, of his private documents.

Nekipelov knew of no country, he said, where a person could be tried for his literary activities.

He was charged with seven poems from the collection Anaesthesia. But a collection is a complete work of literature, and to extract poems from it is the same as quoting a few sentences extracted from a text and judging the whole text by them. He stated that his poetry was his own personal reaction to various events. They contained no libel, and the same was true of the articles and literary essays “About Our Searches”, “Erased from the Facade”, “Why Didn’t I Sign the Stockholm Appeal?”, “Stalin on the Windscreen”, “To Find a Man” and “When there is no Contest between the Parties”.

As the court had turned down his petition to call as witnesses the co-authors of these documents and the people possessing facts which would have proved that the documents contained no slanderous fabrications Nekipelov refused to give evidence about various documents: the Helsinki Group Documents; letters in defence of Kukobaka, Buzinnikov and Kuleshov; ‘Oprichnina-77’ and ‘Oprichnina-78’; ‘The Faculty of Democracy’ and the ‘Letter in Defence of Little-Known Prisoners’.

Regarding Roy Medvedev’s article “On Volume Three of The Gulag Archipelago“, Nekipelov said it contained criticism of Solzhenitsyn’s book. It could have been published in Soviet newspapers, he said, instead of being used as evidence for a charge of circulating anti-Soviet literature.

Procurator Salnov considered Nekipelov’s guilt to have been fully proven, and demanded the maximum sentence: seven years strict-regime camp and five years in exile.

*

Speech for the Defence

In his defence speech Nekipelov pointed out that the documents with which he was charged contained no libel. He also said that the investigation and the Procurator had pronounced them anti-Soviet without proof, while part of the court’s task was to assess whether this assertion had been proved.

However, the court had refused Nekipelov’s request to call witnesses who had suffered for their convictions and had been, or were at present, imprisoned. Instead they had called Nadezhkin and Petrov, who had given false evidence about conditions in the camps. This was the same as if at the Nuremberg trials the witnesses had been not the victims of Fascism, but only the organizers of mass extermination.

From Nekipelov’s final speech:

“I consider myself innocent, and believe that I should be acquitted. I know what sentence will be pronounced, however: it has been decided in advance. I do not ask the court for leniency, because that would contradict everything I have said here.

“I am 52 years old and a sentence of seven years imprisonment and five years exile for me means life imprisonment.”

*

THE SENTENCE

After a meeting lasting two-and-a-half hours, the court delivered its judgment, which included all the episodes in the indictment. It mentioned in particular that the testimonies of the salesgirls, who had said that Nekipelov repeatedly asked for paper, provided evidence of the intent to circulate. Nekipelov was sentenced to seven years imprisonment in strict-regime camps, followed by five years exile.

*

Nekipelov’s case file contains the testimony of a certain female criminal.

She was allegedly told by Malva Landa in a transit prison that Ivan Kovalyov, on the instructions of Nekipelov, had concealed a dissident radio transmitter, or printing press, somewhere in Lithuania. The case file contains a mention that materials of some sort on M. Petrenko have been sent to the KGB district office.

There is also a letter from Apraksin, Chairman of the Moscow Bar Association.

Writing to one of Andropov’s deputies, KGB Major-General Ponomaryov, Apraksin says: In accordance with their agreement, he is sending a refusal to supply a Moscow barrister to Nekipelov’s wife and son, signed by his deputy Sklyarsky (CCE 56.3 [4]).

*

During the investigation Nekipelov was held in a ward with tubercular patients.

He was subjected to a psychiatric examination. Brought in ostensibly for examination by a dermatologist, Nekipelov found a psychiatric commission in the office. He refused to speak with its members. The entire ‘assessment’ lasted five minutes. He was not examined.

Conclusion: “A psychopathic individual, but responsible for his actions.”

*

VISIT

On 17 June 1980, Victor Nekipelov was granted a two-hour meeting in Vladimir Prison with his wife and eldest son Sergei (his son’s wife was not allowed to visit him, despite the fact that the Judge had given her permission). Instead of the two hours they had been allowed, they were given one hour and 45 minutes.

They were forbidden to discuss the trial, an appeal, a lawyer, or even their twelve-year-old son Yevgeny. When they mentioned relatives with the same first names as those of prisoners whom Nekipelov had defended, the telephone was cut off, “we know who you’re talking about”. He was forbidden to read his wife some poems he had written for 22 June 1980, their 15th wedding anniversary. They were forbidden to read out telegrams addressed to Victor Nekipelov, or to discuss the family’s financial situation. They were allowed to discuss only ‘everyday’ subjects.

During the previous week, said Nekipelov, he had suffered from continual migraines, and from pain in his knees (arthritis) and lower spine. He was having difficulty walking; one leg hurts when he uses it. He was in urgent need of a dentist; he was refused treatment during the investigation, as he was there ‘temporarily’.

Nekipelov said he was not permitted to have T-shirts, even short-sleeved ones.

He has thick boots, and doubts that he will be sent to camp wearing them: for him “tarpaulin boots are required” (at the trial he had to wear his boots, in spite of the heat; he was not permitted to put on shoes). He also asked to be sent an English language text-book. The visit was continually interrupted with threats that it would be cut short.

After the visit the Deputy Head of Vladimir Prison, N.V. Fedotov, forbade Komarova to give her husband what he had asked for during the visit: a plastic mug, a bag and foot-cloths,

*

APPEALS

On 14 June 1980, Andrei Sakharov wrote a letter in defence of V. Nekipelov:

“… I appeal to heads of governments who signed the Helsinki Agreement, to writers and poets, to Amnesty International; I ask all concerned with human rights and justice to do everything possible to obtain the release of Victor Nekipelov. There is much that is terrible and unjust in the world today. But the fate of one man who has done so much for others — this Is something worth fighting for.

“Two years ago, Nekipelov and other Moscow Helsinki Group members appealed for a political amnesty in the USSR, something so desperately needed by our country, tormented as it is by sixty years of political oppression, and for an amnesty for prisoners of conscience all over the world. Today I repeat this appeal once again.”

*

On 17 June 1980, the MOSCOW HELSINKI GROUP adopted Document 137, “The Trial of Victor Nekipelov”:

“… From the statements Victor Nekipelov made at his trial it follows that his involvement in the Moscow Helsinki Group is in fact the main charge against him.

“The court did not seek to prove Nekipelov’s ‘guilt’; it attempted only to create the superficial decorum of the process of justice. In particular, the court turned down Nekipelov’s petition that all the Helsinki Group Documents be investigated and more than twenty additional witnesses be called to confirm the facts recorded in the articles, letters and documents with which Nekipelov was charged.

“Nekipelov’s evidence was ignored by the court. The court blocked all Nekipelov’s attempts to obtain a consistent and objective examination of the episodes with which he was charged, and ‘proved’ Nekipelov’s ‘guilt’ by means of contradictory and sometimes downright false evidence of witnesses on incidental episodes of little significance.

“We maintain that the trial and arrest of Victor Nekipelov constitute yet another crude violation of the Final Act of the Helsinki Conference.”

=========================================

NOTES

- First published in November 1962 in the Novy mir periodical (print run 97,000 plus 25,000; editor, Alexander Tvardovsky, see CCE 23.10), “Ivan Denisovich” was republished two months later in 700,000 copies by Roman-Gazeta (January 1963).

↩︎ - Moscow venue for the annual Human Rights Day demonstration (10 December), staged by dissenters since 1965.

↩︎ - “A collection of verse written mostly in 1974-1975 (CCE 32.4), while Nekipelov was in the camps,” says ‘Samizdat Update’, CCE 42.12 [8]. That October 1976 issue also refers to his classic Institute of Fools.

↩︎ - “Oprichnina-77” (CCE 45.20 [2], CCE 46.20 and CCE 48.24) was co-authored with Tatyana Khodorovich. “Oprichnina-78” (CCE 51.21 [4]) was co-authored with Tatyana Osipova.

↩︎ - Victor Nekipelov was born in northern China, in the city of Harbin, in 1928. At the age of 9, he and his mother moved back to the USSR in 1937.

↩︎ - See <<Moscow Helsinki Group (documents 1-195): 1976-1982>>.

↩︎

=========================