PETROV-AGATOV ARTICLE

On 2 February 1977 an article, “Liars and Pharisees”, was published in the weekly Literaturnaya gazeta under the signature of A. Petrov (Agatov) [1]. Its appearance aroused serious concern for the fate of Alexander Ginzburg and Yury Orlov.

The same day a press conference was called at Ginzburg’s flat.

Alexander Ginzburg told correspondents that in view of the dangerous accusations made against him in the newspaper he had decided to report for the first time the details of his work as representative of the Relief Fund, the “Fund to Aid Political Prisoners & their Families” [2].

♦

FUND

The fund was established by Alexander Solzhenitsyn in April 1974, drawing on the royalties for The Gulag Archipelago (CCE 32.1).

Part of the money was left by the Solzhenitsyn family before their departure from the USSR in February-March 1974; part was received in 1974-1975 in the form of money certificates. From the beginning of 1976, Ginzburg himself stopped receiving transfers from abroad in his name. The only way he had received money from abroad since then, Ginzburg said, was when people brought him Soviet money and said: “This is money which Solzhenitsyn asked to be given to you for assisting political prisoners.”

In addition, about 70,000 roubles were collected in the Soviet Union.

A thousand people gave money to the fund. In three years 270,000 roubles were received and distributed. In 1974 assistance was rendered to 134 political prisoners and their families; in 1975 it went to more than seven hundred families; and in 1976, to 629 families. The decrease in the number of families in 1976 can be partly explained by the threats to which many people who benefited from the fund were subjected (in particular, those in exile were threatened that their situation would worsen). Besides regular help to political prisoners and their families, help has been given on a once-only basis to people released from the camps or from prison.

“If I am now arrested,” said Ginzburg, addressing the journalists, “then I ask you to pay great attention to the work of those who replace me, as they will certainly need it.”

♦

ARREST

The following day, 3 February 1977, Alexander Ginzburg was arrested.

His wife Arina Zholkovskaya-Ginzburg described his arrest in a letter to Amnesty International:

“… On the evening of 3 February my husband went out, lightly dressed, to make a call from a phone box: the phone in our flat was cut off long ago by the authorities. He went out and did not come back.

“Alexander was seized at the entrance to our building; it was not considered necessary to inform me of this. Leaving my two small children at home, myself sick and with a temperature, together with friends I drove round police stations all evening. Finally, at the KGB reception, by then it was night time, I was told that according to their information my husband had been arrested. The following day it became clear that arrested meant he was being held in custody.

“The same evening, 3 February 1977, knowing full well about my husband’s illness, KGB officials transferred him to Kaluga Prison. Kaluga is 200 kms from Moscow …”

A. I. Ginzburg is being held at the Kaluga Investigations Prison (110 Klara Zetkin Street, postbox IZ 37/1).

The case is being conducted by Lieutenant-Colonel Oselkov, Senior Investigator for Especially Important Cases of the Kaluga Region KGB.

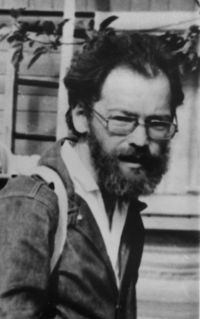

Alexander Ginzburg (1936-2002)

♦

BIOGRAPHY

Alexander Ilych GINZBURG was born in Moscow on 21 November 1936.

After finishing school he worked in a theatre, as an actor and assistant director, and as a newspaper reporter. In 1956 he entered the faculty of journalism of Moscow University.

In 1960 he put together the samizdat poetry anthology Syntaxis, which published the verse of the SMOG poets [3], of Bella Akhmadulina and Genrikh Sapgir. Ginzburg’s own poetic efforts were also printed in the collection. The same year Ginzburg was arrested and convicted of forging documents: he had sat some examinations for a friend.

*

In 1962, after his release, having with difficulty registered as a resident of Moscow, Ginzburg tried to get work of some kind. Everywhere he met opposition from the powers that be. He worked in sewage disposal, as a lathe operator, as a laboratory assistant and a librarian.

In 1964 Ginzburg was held for a few days at KGB headquarters in the Lubyanka.

Shortly afterwards a letter appeared in the Vechernyaya Moskva (Evening Moscow) newspaper under Ginzburg’s signature, in which he dissociated himself from the sensation around his name in the Western press.

Ginzburg did compose a letter of this sort, but the published text had little in common with that of the author.

*

In 1966 he entered the Historical Archives Institute as a student. In 1967 Ginzburg was arrested for compiling the White Book [4], a collection of materials about the trial of Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuly Daniel.

In January 1968, Ginzburg was convicted (CCE 1.1) under Article 70 (RSFSR Criminal Code) together with Yury Galanskov, Vera Lashkova and Alexei Dobrovolsky. The “Trial of the Four” aroused a stream of protests (CCE 1.2). This proved the beginning of systematic resistance to the violation of human rights in the USSR: it also prompted the founding of the Chronicle of Current Events.

Ginzburg spent his five years of imprisonment in the Mordovian camps, then in Vladimir Prison.

*

In 1972 Ginzburg was released at the end of his term and settled in Tarusa [5], a small town in the Kaluga Region.

In the years that followed, he was subjected to constant oppression and reprisals. Twice he was placed under administrative surveillance, and he was not allowed to visit Moscow to see his mother, wife and children. Obstacles to employment were put in his way, for even the most unskilled job: at the same time attempts were made to bring him to trial for “parasitism”.

Since 1974 Alexander Ginzburg has been the official representative of the Fund to Aid Political Prisoners & their Families. He has been a member of the Helsinki Group (CCE 40.14) from the moment it was founded.

While Ginzburg was in the camps he developed an ulcer from which he suffers to the present time.

Soon after the 4 January 1977 search Ginzburg entered hospital: he was diagnosed as having pneumonia with an underlying tubercular infection. On being discharged he was referred to a TB Clinic. At the moment of his arrest he was still undergoing regular treatment. In the first few days of February Ginzburg should have gone into hospital for treatment of his ulcer.

Ginzburg has two children, aged four and two.

♦

REACTIONS

OFFICIAL

On 4 February 1977, the day after Ginzburg’s arrest, the TASS news agency made the following announcement for readers abroad:

“… Ginzburg was arrested with the approval of the Kaluga City Procurator for activities at variance with the law. He is a character without a definite occupation, a parasite who began his career with speculation and buying up icons.

“In 1961 he was convicted of cheating, and in 1968 he received 5 years for anti-Soviet activities. Already at that time links were discovered with NTS, the pro-fascist émigré organization, which, as is well known, is linked with Western secret services.

“After his release he continued to be actively engaged in anti-Soviet activities, the specific nature of which, one must suppose, will be disclosed during the investigation. As has already been announced, a search was carried out at Ginzburg’s flat, as a result of which materials were confiscated which testify to his direct links with the NTS, also anti-Soviet brochures and Zionist lampoons, and a large quantity of Soviet and foreign currency…”

♦

APPEALS

On 4 February 1977 people began signing a collective statement in defence of Alexander Ginzburg.

It speaks of his extensive activities as a manager of the Relief Fund (to Aid Political Prisoners) and as a member of the Helsinki Group. It points out that Ginzburg’s activities have continually elicited libel on the part of the Soviet media.

“The trial, if indeed it takes place, will be the revenge of the authorities on a courageous man, for his charity and kindness. The sentence, if indeed it is pronounced, will be equivalent to the murder of a father of two young children.”

The letter demands Ginzburg’s immediate release.

It bears 321 signatures. Among the signatories are inhabitants of various Soviet towns and cities: friends and acquaintances of Ginzburg; former political prisoners and exiles; representatives of various dissident groups; Jews who have been refused exit visas; representatives of religious communities; and independent artists.

Many other letters in defence of Ginzburg have appeared (see CCE 44.27 “Letters and Statements”).

♦

On 4 February at a press conference the Helsinki Group and the Action Group announced that Ginzburg’s successors as managers of the Relief Fund (CCE 46.16) would be Tatyana Khodorovich, Malva Landa and Kronid Lyubarsky.

The joint statement of the groups was handed to journalists. It spoke of the alarming situation that had arisen recently, and announced that the KGB was now hunting for Yury Orlov.

♦

SEARCH 1

On the evening of 6 February a search linked to the Ginzburg case was carried out in Tarusa at the home of Ukrainian Helsinki Group member, Nina A. Strokata (Strokatova). The search was led by Lieutenant-Colonel Oselkov. None of those conducting it besides Oselkov showed any documents. Oselkov himself stated that they were “his boys” and witnesses, but it was not permitted to see their documents.

The brigade searched Strokata’s house and the personal effects of her guests: Yelena Danielyan, Lyubarsky, and his wife Galina Salova. The record of the search was compiled extremely carelessly and after protests was written afresh.

During the search Oselkov spoke rudely and when asked to be more polite began to threaten that he would call the police and remove the guests from the house.

Salova and Danielyan tried to add comments to the record, but Oselkov forbade them [6] to do so: “It’s clear to me”, he said, “what sort of people you are.” A Declaration of the Ukrainian Helsinki group, samizdat, and letters in defence of Ginzburg were confiscated during the search.

♦

On 9 February 1977 Pyotr Grigorenko, Zinaida Grigorenko, Valentin Turchin, Sofia Kalistratova, Andrei Sakharov, Lydia Chukovskaya, Lev Kopelev, Alexander Korchak and Yelena Bonner appealed to the Kaluga Region Procurator to change the measure of restraint imposed on Ginzburg.

They asked that he be released him from custody on their personal guarantee, or on bail, until the trial began. The authorities are obliged by law to reply within a period of two weeks, but there was no response whatsoever.

♦

SEARCH 2

On 25 February 1977 a search was carried out at the Tarusa home of Ginzburg.

The search warrant, signed on 2 February 1977, indicated that the case was being investigated according to Article 70, pt. 2 (RSFSR Criminal Code): it was not known until then under which article Ginzburg was being charged.

Lieutenant-Colonel Oselkov conducted the search. Lieutenant-Colonel Nikiforov, and Lieutenants Danilov, Pustoshinsky, Petrachenko and Klimenko also took part. The search was carried out in the presence of Kronid Lyubarsky and Oleg Vorobyov, whom they brought to the house; they were registered as residing there [correction CCE 45.22].

The search lasted from 12 noon on 25 February until 6.50 am on 26 February 1977. Those carrying it out were rude and did not bother, especially, to observe legal formalities.

The KGB officers confiscated textbooks for studying foreign languages, dictionaries, and books in foreign languages, including one by the American poet Allen Ginsberg with his verses against the Vietnam War. They removed an unused film, notebooks, old carbon paper and various notes about political prisoners. They took away two of Ginzburg’s letters from Vladimir Prison, his appeal against his sentence to the Procurator and the speech of Ginzburg’s lawyer Boris Zolotukhin at the 1968 trial. They confiscated a knife from Ginzburg’s work room.

In the storage space above the kitchen door they found a box containing samizdat from the 1968-1970 period and copies of various court verdicts and statements to official bodies (including statements by Ginzburg himself). They called the box a hiding-place and spent a long time photographing it.

In the West Andrei Amalrik, Vladimir Bukovsky, Natalya Gorbanevskaya, Pavel Litvinov, Natalya Solzhenitsyn and Valery Chalidze issued protests against Ginzburg’s arrest.

♦

DEFENSE

Alexander Solzhenitsyn has requested the famous American lawyer Edward Bennett Williams to take on the defence of Alexander Ginzburg at the forthcoming trial.

In his letter to Williams, Solzhenitsyn wrote that Alexander Ginzburg, as representative of the Relief Fund, had rendered assistance to hundreds of political prisoners and their oppressed families. In conditions of constant opposition from the Soviet authorities this work demanded unusually noble human qualities. Solzhenitsyn expressed his certainty that the Soviet authorities, unable to charge Ginzburg directly for his charitable activities, would raise false charges against him. Solzhenitsyn ended by saying that, without fail, he would bring to the lawyer’s notice every detail of the case.

Williams replied that he would take on the case and submit a visa application to the Soviet embassy in order to go and see his client. Williams considers that his chances of receiving an entry visa and access to the case are slight, although certain points of the Helsinki Agreements give a legal basis to such a request.

(In 1961, at the request of the Soviet Embassy in the USA, Williams took on the defence of G. Melekh, a Soviet employee at the United Nations, who had been charged with espionage. The case did not go to trial, as agreement was reached on Melekh’s expulsion from the country.)

=================================

NOTES

- On Petrov-Agatov, see CCE 10.15 [21], CCE 11.3, CCE 12.10 [18], CCE 17.12 [9] and Name Index.

↩︎ - The Relief Fund continued for many years.

It did not formally cease to exist until 1997: see Afterword (pp. 496-498) to the abridged & revised 2018 edition of the single volume Gulag Archipelago (pbk, Vintage Classics: London).

Often referred to in colloquial terms as the “Solzhenitsyn” Fund, it was formally known as the Public Fund: sometimes “obshchestvennyi” was (misleadingly) translated to mean “Social” Fund.

↩︎ - The jocular self-description SMOG is interpreted to mean “the Youngest Society of Geniuses”.

↩︎ - Most of the same material appeared in Labedz and Hayward (eds.), On trial: The case of Sinyavsky and Daniel (1967).

↩︎ - Tarusa (pop. 6,025, 1970) is 101 kilometres from Moscow. Restricted in their post-sentence proximity to the Soviet capital or any other major urban centre, many former political prisoners and dissidents (Anatoly Marchenko, Kronid Lyubarsky, Nina Strokata) settled in Tarusa.

It was also, tragically, the place where returnee Marina Tsvetayeva committed suicide in 1941.

↩︎ - The restriction on adding comments to the search record did not apply to Galina Salova (CCE 45.22 [1]).

↩︎

==========================