On 8 December 1978 criminal proceedings were instituted against Josif Samoilovich ZISELS (b. 1946); on the same day as he was arrested (CCE 52.4). The indictment stated that materials from the criminal case against D. I. Margulis (??CCE 51 & CCE 52.4) and G. M. Gurfel, separated out on 21 November 1978, served as the grounds for instituting criminal proceedings.

From 3-5 April the Chernovtsy Regional Court, presided over by its Deputy Chairman, V. S. Ishchenko, examined the case against Zisels, who was charged under Article 187-1 (UkSSR Criminal Code = Article 190-1, RSFSR Code). The prosecutor was First Assistant Procurator of the Chernovtsy Region, Kotsyurba.

The defence lawyer was Nelly Nimirinskaya from Voroshilovgrad [Luhansk] who had earlier defended Bidiya Dandaron (Ulan-Ude CCE 28.6 1972); Victor Khaustov (Oryol CCE 32.2 1974); Victor Nekipelov (Vladimir CCE 32.4 1974); Lev Roitburd (Odessa CCE 37.3 & CCE 38.19 1975); Vyacheslav Igrunov (Odessa CCE 40.5 1976); and Vladimir Rozhdestvov (Kaluga CCE 47.2 & CCE 48.12 1977).

*

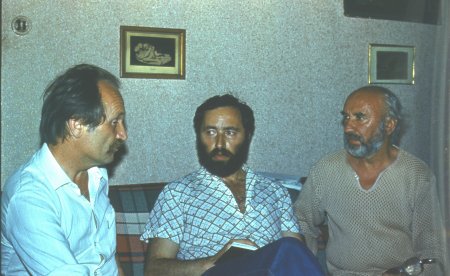

Chornovil, Zisels and Krasivsky (1988 photo)

The trial took place on the premises of the Sadgorsky district people’s court in Chernovtsy. The location of the trial was announced on the morning of 3 April.

On 3 April, apart from the ‘special public’ only the wife of the accused, Irena Zisels, was allowed into the courtroom; she was ordered beforehand to leave her handbag; during the break the police took her notes away. P. A. Podrabinek (CCE 48.7) who had arrived from Moscow, was escorted to a police station, where he was detained until the evening. He was then taken to the airport and put on a plane back to Moscow, without even being allowed to collect his things. The police ‘advised’ the brother of the accused, Semyon Zisels, and other friends not to stand near the court building. When they refused to move away, they were taken to the police station, where they were detained until about 3 pm.

At the beginning of the trial J. Zisels petitioned for his friends and relatives and, by name, P. A. Podrabinek, to be let into the courtroom. At about 2 pm, after the break, the court acceded to the petition, but the head of the escort, who was sent to implement the court’s decision, came back and reported that there was no one in front of the court building. On 4 April Josif Zisels’s mother and his brother Semyon were allowed into the courtroom as well, and on 5 April, Josif’s mother-in-law.

KGB officials under the command of Lt.-Col. Vishnevsky were controlling everything going on in and around the courtroom. They were always in the room where the Judge rested during the breaks, and gave orders on whom to allow into the courtroom, whom to take to the police station, etc.

*

TRIAL

At the beginning of the trial J. Zisels objected to the composition of the court and to the Procurator, reasoning that because of the structure of our State a court could be composed only of people who completely and fully supported the policies of the Party and the State, and that the very fact of his trial showed that several aspects of these policies were in need of serious criticism. To the Judge’s question as to what court could decide his case, J. Zisels answered that a case of this type should be under the jurisdiction of an international court of human rights. After 45 minutes’ consultation the court overruled his objection.

J. Zisels repeated his petition submitted during the pre-trial investigation to call 580 witnesses and conduct 139 confrontations and examinations to determine the truth of the facts contained in the incriminating documents (listed were people discussed in these documents, and their authors — Solzhenitsyn, Nekipelov, Osipova and others).

Eight witnesses out of the 23 who had been examined at the pretrial investigation were summoned to appear at the trial. Zisels petitioned for the other 15 witnesses to be called also.

He also petitioned for the examination in court, in the category of material evidence, of several documents confiscated from him during a search on 10 November 1978 (CCE 51.8), in particular D. Kharms’s collection The Event and journals containing the article by A. Belinkov, ‘The Poet and Fat Man’. The court rejected all these petitions.

J. Zisels enumerated 29 Articles of the Code of Criminal Procedure which had been completely or partially broken during the pre-trial investigation.

*

INDICTMENT

The indictment consisted of the following charges:

- The circulation of ‘slanderous literature’: in Kishinyov in 1974-5 he acquainted I. Shenker with Andrei Amalrik’s article ‘Will the Soviet Union Survive until 1984?’, with Solzhenitsyn’s letter to the Fourth Congress of Soviet Writers, and with his Nobel speech; in 1976 he gave V. Kruglov and Semyon Zisels The Gulag Archipelago to read’; in 1976 he gave R. Blitt the collection From Under the Rubble,’

- The preparation and possession with the purpose of circulation of two ‘handwritten texts’ (a) a synopsis of Solzhenitsyn’s article ‘Live Not by Lies’ and a list of questions on human rights; and (b) one ‘typewritten text’, an appeal in defence of A. Podrabinek (under this appeal Zisels had added to the typewritten signatures 16 names in his own handwriting).

- Possession with the purpose of circulation of the collection Live Not by Lies (CCE 32.18), two issues of Oprichnina-78 Continues (CCE 51.21 [4]). two bulletins of the Working Commission to Investigate the Use of Psychiatry for Political Purposes, A. Solzhenitsyn’s This is How We Live, brochures entitled Aid to Political Prisoners in the USSR (CCE 46.16), a letter by A. Belinkov, and appeals in defence of Orlov, Shcharansky and Ginzburg.

- The circulation of oral ‘slander’: in 1976 and 1978 Zisels said to witness I. Ostapenko that human rights are violated in the Soviet Union, people do not have the right freely to live anywhere, and Jews do not have opportunities for higher education; in March 1978 Zisels told N. Sakharova in Moscow that the authorities distort the facts regarding the development of socialist society and forcibly place healthy people in psychiatric hospitals for political reasons.

- The collection of tendentious information (a card index on 77 prisoners in special psychiatric hospitals, CCE 51.11).

J. Zisels declared that he was not guilty of any of the charges, in so far as there was no slander contained either in the materials confiscated from him or in his utterances.

Zisels refused to answer questions about where and from whom he had obtained any of the documents; when questioned about the purpose of his possessing them he gave a short account of each document and explained that he was interested in their themes; he declined to answer a question on whether he shared the opinions of t e authors, as this was a question which concerned his convictions. He neither confirmed nor refuted the evidence of the witnesses and the results of examinations by experts. He refused to answer any question which concerned third parties.

Here is an excerpt from the examination of J. Zisels:

Lawyer: Have you come across the sort of facts stated by Solzhenitsyn in The Gulag Archipelago anywhere else?

Zisels: Yes, I’ve come across some of these facts from other sources.

Lawyer: What are these sources? Were they published officially?

Zisels: Yes, they are official sources, namely the books 1941: 22 June by Nekrich, A Tale from Experience by Dyakov, One Day in The Life of Ivan Denisovich by Solzhenitsyn, the memoirs of G. Serebryakova and materials from the 20th and 22nd congresses of the CPSU.

*

WITNESSES

On 4 April the witnesses were examined.

N. V. Kruglova confirmed that in 1976 she had become acquainted with the book The Gulag Archipelago, which had been brought by her son from J. Zisels. To the Procurator’s question: ‘In what circumstances did Zisels offer you this book to read?’ Kruglova replied, ‘No, he didn’t offer it me to read. He telephoned and suggested coming to see me with my son. My son came on his own and brought the book’. The first sentence of this reply was not included in the record, in spite of Zisels’s objection.

V. Kruglov, too, confirmed that he had borrowed The Gulag Archipelago from Zisels in 1976. To the Procurator’s question, ‘In what circumstances did you take this book?’ he replied, ‘I noticed it on a table and asked Josif to lend it to me to read. Josif only gave me the first part’. The first sentence of this reply was again not included in the record.

R. Blitt confirmed that in 1976 he had borrowed From Under the Rubble from J. Zisels. To the Judge’s question: ‘Did you choose the book yourself or were you offered it?’ he replied, ‘I chose it myself’. Neither the question nor the answer was included in the record.

I. Shenker declared that he could not remember whether Zisels had shown him Amalrik’s article and Solzhenitsyn’s letter and speech.

Judge: On the record of your interrogation on 29 January 1979 you wrote in your own hand that your words had been noted correctly, and your signature is there.

Shenker: The record of 29 January 1979 was compiled by the investigator on the basis of the explanations I had given to the Kishinev KGB in February 1977. That was the first time in my life that I’d been to the KGB and I was in a terrible state.

Judge: On 29 January, when you wrote an addendum to the record and signed it in your own hand, were you in a normal state?

Shenker: I didn’t want to contradict the evidence which I’d given to the KGB.

Judge: Witness, do you exclude Zisels from the circle of people who might have acquainted you with this document?

Shenker: Yes, I exclude him.

Judge: Why?

Shenker: If only because he’s my friend.

The Procurator demanded that a criminal case be instituted against Shenker for giving false evidence and that he be arrested in the courtroom.

According to the evidence of I. Ostapenko, a colleague of Zisels, the accused had said to him that it is made difficult in our country for Jews to get higher education and that their attempts to emigrate to Israel meet numerous obstacles.

Judge: Witness, what is your relationship to the accused?

Ostapenko: After 1976, when I discovered from an article in the Regional newspaper what unattractive activities Zisels was engaged in — reading the works of Solzhenitsyn [CCE 44.12-15] — I could not respect him.

Lawyer: Did Zisels utter any fabrications discrediting our society and state?

Ostapenko: No.

Zisels: Who was present at our conversation?

Ostapenko: Zakharov, Yaremkevich and other people who worked in the accounts department. (The two last questions and answers were not included in the record.)

From the examination of Zakharov (who was examined before Ostapenko):

Judge: Were you present during a conversation between Ostapenko and Zisels about human rights being violated in our country? Zakharov No, I don’t remember.

Lawyer: Have you ever seen Zisels in the company of Ostapenko and Yaremkevich?

Ostapenko: No, I haven’t.

(These two questions and answers were not included in the record.)

After the examination of Ostapenko, Zisels stated that his testimony was false, that it was disproved by the testimony of Zakharov and Yaremkevich given at the pre-trial investigation and by Zakharov’s testimony at the trial (Zisels’s petition to summon Yaremkevich to appear in court was turned down, see above).

N. Sakharova’s mother sent the court a telegram saying that her daughter was in hospital. J. Zisels and his counsel requested that the session be postponed until her arrival, or that her evidence be disregarded. In addition to this, Zisels announced that N. Sakharova had not been to Chernovtsy to give evidence to the pre-trial investigation and that her signature on the interrogation record of 21 December was a forgery. The court rejected the petition of Zisels and counsel and decided to read N. Sakharova’s evidence from the record in question. According to this evidence N. Sakharova understood, from a conversation with J. Zisels, that in our country, a few historical facts have been consciously distorted by the official organs and that people who try to tell the truth are subjected to compulsory treatment in psychiatric hospitals’.

The last witness to be called, Semyon Zisels, not having received a summons, was in the courtroom during the examination of the accused and other witnesses. The court, therefore, decided not to use his evidence. At the pre-trial investigation S. Zisels had refused to give evidence and did not confirm the explanation which he had given in 1976 about The Gulag Archipelago (CCE 52.4).

*

FINAL SPEECHES

From the Procurator’s speech:

‘The accused Zisels believed bourgeois propaganda; he believed that in the Soviet Union elementary democratic rights and freedoms are violated.’

The Procurator repeated all the accusations made in the indictment and demanded three years’ hard-regime camps for Zisels.

In her speech defence counsel Nimirinskaya pointed out that not the slightest effort had been made, either at the pre-trial investigation or at the trial, to demonstrate falsity in the facts contained in the documents incriminating the accused; at the same time the petitions of the accused, aimed at establishing their truthfulness, had been turned down. Thus Zisels’ guilt was not proven:

‘It occurs to me to doubt whether either the investigator or the Procurator is acquainted with the text of Article 187-1 of the Ukrainian Criminal Code. Possession of books and documents is not mentioned, you know, in Article 187-1.’

At the beginning of his prosecuting speech, the Procurator refuted his own accusation in his own words. He said that through reading anti-Soviet literature Zisels believed that human rights were being violated in the Soviet Union. Where then is the deliberate fabrication?

Going through each of the episodes and pieces of evidence incriminating Zisels one by one, his defence lawyer showed that they were either not proven or not incriminating, and asked the court to acquit the accused.

From J. Zisels’ final speech:

‘I maintain that the investigators and the court had decided my guilt before even beginning to examine the essence of the case. The Procurator in his prosecuting speech substituted for evidence of

my guilt a long story about the great successes of our country and the subterfuge of the imperialists …

‘Today the court was again faced with books. The history of mankind can be seen as the history of man’s and society’s attitude to the book. But if there are somewhat varying attitudes to the books that are being destroyed, the attitude to authors is always and everywhere the same. They are either declared lunatics, like Radishchev and Chaadayev, N. Korzhavin and Z. Medvedev, or they are put on trial like Dostoyevsky and Korolenko, Daniel and Sinyavsky, or they are killed like Pushkin and Lermontov, Gumilyov and Mandelshtam, Babel and Vesyoly. On the one hand — the superpower with all its attendant attributes of force, ideology and propaganda, on the other — just a few sheets of paper; and the outcome of the duel is decided in advance: the book always wins

‘I searched for my path in life for a long time… and found it in the river-bed of an old tradition. This tradition is resistance to violence and lies. Its weapons are words of truth and a sympathetic concern for the deceived, and help for those to whom violence is applied. I’ve only just set out along this path, taken a few steps along it, but I’m happy that I’ve managed to find it, managed so well that I’ve found myself in prison. Lies and violence are particularly concentrated in places of imprisonment. And where could a word of truth and sympathetic concern be more necessary than there? …

‘I am grateful to everyone who has passed through the political repressions of the last 200 years of Russian history with honour — from Radishchev to those sentenced at the trials of 1978. 1 am in debt to these people because they have taught me to feel a free and proud man even behind the stone walls of a prison. I bow before their clear, noble and deeply moral position. They could, you know, have uttered just two words: ‘I recant!’ — and warmth and comfort, health and a full stomach would have been restored to them; but they did not say those words.

‘I ask the forgiveness of my dear ones and my acquaintances for what they have had to endure.

‘To the Judges, who are not in a position to give an independent and just verdict, I have nothing to say.’

‘The judgment was pronounced on 5 April. Its descriptive part differs from the indictment on two points (the ‘acquainting’ of Semyon Zisels with The Gulag Archipelago and of Shenker with Solzhenitsyn’s Nobel speech), and substitutes ‘possessed with the purpose of circulation’ for ‘obtained and used for circulation’. The court sentenced Zisels to three years in a hard-regime camp.

*

On the same day Irena Zisels issued an appeal:

‘To all who hold truth and justice dear:

‘I am grateful to all the people and organizations who have raised their voices in defence of my husband. Were it not for this support, the lot of Josif Zisels and many others would be much heavier, …

‘I call upon honest people throughout the world actively to join the fight against lies and violence and thus make political and psychiatric repressions impossible.’

*

On 7 April Irena Zisels wrote about the people in the courtroom:

‘Applause by special pass:

‘A courtroom. Around fifty people torn by command from their usual duties. They were all given special passes. It was explained to them that an ‘enemy of the people’ was on trial, and that it was their duty to give a personal demonstration of the people’s indignation and to clap when the sentence was read out…

‘But what do I see I see sometimes eyes, and in them there is evidence that these people, oh horrors, THEY HEAR! And maybe tomorrow they will no longer be able to remain indifferent to people’s unhappiness and sorrow, to the lies and violence around them …’

*

Josif Zisels was shown the record of the trial only on 26 April — after three statements requesting it. He listed 31 additions and corrections. On 4 May a court session was held to review the accuracy of the record. J. Zisels’s petitions were turned down.

On 29 May the Ukrainian Supreme Court examined the appeal of J. Zisels and his lawyer and left the sentence unchanged. On the same day Semyon Zisels for the second time (CCE 52.4-1) appealed to President J. Carter for help:

‘I ask you to do everything that is within your power to ease the lot of my brother Josif Zisels.’

=========================================

NOTES

Zisels was again arrested in Chernovtsy in 1984 (Vesti, 1984, 23-1), put on trial and sent to the camps.

==================