TWENTY-SEVEN ITEMS

[1]

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL

A ‘support group’ [gruppa opeki] of the international non-governmental organization (NGO) Amnesty International has been set up in the Soviet Union.

The aim of Amnesty International is: to aid people whose freedom is restricted in contravention of Articles 5, 9, 18 and 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; to ease their circumstances and; to seek their release.

The work of the support group is governed by the following principles. The group undertakes to help and seek the release of three prisoners: one from the ‘Eastern’, socialist bloc; one from the ‘Western’, capitalist bloc; and the third from the developing countries of Asia, Africa or South America. Prisoners in the support group’s own country are specifically excluded. This system ensures political impartiality in the work undertaken.

The first Soviet ‘support group’ was finally instituted in September 1974. The announcement of the group’s inception was made by 11 people and was dated October 1973.

Those wishing to take part in the work of the Soviet group can contact Valentin Turchin, the group’s chairman (telephone: Moscow 129-25-30), or the group’s secretary, Andrei Tverdokhlebov (telephone: Moscow 297-63-69).

*

[2]

In September 1974 the photographer Vladimir Vylegzhanin (CCE 32.20 [1]) was tried in Kiev. The judge at his trial was Dyshel.

Vylegzhanin was sentenced to four years in a labour camp for ‘Anti-Soviet Agitation & Propaganda’. The court made eight separate rulings. On the basis of two of these the court used Vylegzhanin’s testimony to start separate proceedings against the Muscovites Sergei Bychkov and Nikolai Bokov (CCE 32.20 [1]).

During a visit from his wife after the verdict Vylegzhanin said that he would be celebrating his 30th birthday in freedom; he was born in 1945.

Judge Dyshel also presided at the trials of:

- Zinovy Antonyuk (CCE 27.1 [3]; sentence 7 years camps + 3 years exile);

- Vasyl Stus (CCE 27.1 [4]; sentence 5 + 3);

- Semyon Gluzman (CCE 28.7 [1.4]; sentence 7 + 3);

- Lyubov Serednyak (CCE 28.7 [1.4]);

- Leonid Plyushch (CCE 29.6; SPH compulsory treatment); and

- Yevhen Sverstyuk (CCE 29.5 [2]; sentence 7 + 5).

*

[3]

Pyotr Yakir and Victor Krasin were pardoned on 16 September 1974 by a decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet [1], and have been freed from serving the rest of their sentences (CCE 30.2).

*

[4]

In February 1973 Petros Cidzikas (b. 1944), a student at Vilnius University, was arrested.

In June 1973 the Supreme Court of the Lithuanian SSR heard the case of Cidzikas, charged with disseminating the Chronicle of the Lithuanian Catholic Church, anti-Soviet pamphlets and nationalist poetry. The court declared Cidzikas insane and sent him to a Special Psychiatric Hospital for compulsory treatment. He was transferred to the Chernyakhovsk SPH (Kaliningrad Region).

To avoid being conscripted into the Soviet army, Cidzikas had earlier pretended to be mentally ill and was exempted from military service.

*

[5]

On 18 September 1974 the Supreme Court of the Lithuanian SSR sentenced B. Kulikauskas (arrested, 20 November 1973) to 3 ½ years in a strict-regime labour camp, and J. Ivanauskas to two years of ordinary regime for “stealing State property”.

The facts of the case: Ivanauskas gave some typing paper to Kulikauskas, who used it to print prayer-books. This was the second time Kulikauskas had been tried for printing prayer-books.

*

[6]

After their release from imprisonment, the brothers Anatoly and Valery Rumyantsev (CCE 19.11 [12], CCE 20.7) were not given residence permits to live with their blind mother, who lives on her own in Sochi (pop. 241,000; 1973).

Valery was placed under police surveillance for a year in the small city of Tikhoretsk (Krasnodar Region [Krai]). The police allowed Valery to visit his mother twice, but refused to permit a visit at the New Year. His mother cannot go to live with Valery or even visit him, as he does not have accommodation of his own.

*

[7]

ANATOLY ZINCHENKO

During a tourist excursion on the Danube in October-November 1972 Anatoly Mikhailovich ZINCHENKO, an engineer from Kharkov, paid a visit to the West German embassy (Federal Republic of Germany) in Vienna “to examine the possibility of obtaining work and accommodation if he were to come officially with his family to Germany for a time”.

*

Zinchenko missed his boat and, at his own request, was taken by the consul to the Soviet Embassy; from there he was flown to Moscow. At Moscow airport he was arrested and, escorted by KGB officials, was sent to Kharkov at his own expense. He was held under arrest from 8 to 13 November 1972. A criminal case was prepared against Zinchenko for “Betrayal of the Motherland” (Article 64) [2].

Procedural norms were violated during the investigation; witnesses were subjected to blackmail and threats. Zinchenko’s 73-year-old mother was questioned for 10 hours, for example, during which time she was told he had given evidence against himself and that she must confirm this evidence in order to save her son.

At this time Zinchenko and his wife lost their jobs through the influence of the KGB.

Zinchenko himself was deprived of his security clearance and therefore could not continue in his former job. His wife was blackmailed into leaving her place of work. Eleven months later, the charges were dropped, but Zinchenko was given no written confirmation of the closure of the case. Neither Zinchenko nor his wife regained their former jobs.

*

Zinchenko then began a lawsuit against Lieutenant-Colonel Babusenko of the KGB, the chief investigator in his case.

KGB Lieutenant-Colonel Fedosenko came from Kiev and on 24 December 1973 he ‘cautioned’ Zinchenko under the 25 December 1972 Decree, and threatened to charge him with ‘slander’, “making knowingly false accusations” and “spreading fabrications known to be false which defame the Soviet political and social system” (Article 190-1). Zinchenko refused to sign the ‘record of caution’.

Zinchenko sent a number of letters to Soviet Party and State authorities and also to some foreign organizations. In these he makes complaints about the actions of the Kharkov KGB officials. The letters he sent abroad did not reach their destination. Because of this, Zinchenko is carrying on a lively correspondence with the USSR Ministry of Communications.

His address is: Kharkov 103, 41A ’23 August’ Street, flat 9; telephone 302-296.

*

[8]

NIXON ROUND-UP

During the visit to the USSR by US President Nixon between 27 June and 3 July 1974 another ‘Nixon round-up’ took place in Moscow (CCE 26.7).

In particular, a number of Jewish activists were put under preventive arrest. (CCE 32.12 has already reported that participants in the international academic seminar, scheduled for the beginning of July, were arrested.) Those arrested were not kept in Moscow itself but were put in prisons in the suburbs.

Particular care was taken to avoid there being any written evidence of anyone having been put under preventive arrest. The authorities even went to the lengths of ensuring that at their places of work the arrested persons were recorded as having received their wages, and on the time charts their daily ‘arrivals’ and ‘departures’ were marked in.

*

[9]

The physicist Anatoly Shcharansky was detained on 19 June by First Lieutenant A. D. Yefremov, Moscow Criminal Investigation Department, and was held from 19 June to 5 July at the remand prison in in Volokolamsk, 125 kms from the capital.

Shcharansky received no explanation of his detention, but was told his wages would be paid for the period of his absence. Despite a verbal directive from the KGB, however, the department of personnel & accounts at the All-Union Oil and Gas Research Institute refused to pay Shcharansky any wages for the days of his ‘preventive absence’. Shcharansky filed a statement of claim in court, demanding fulfilment of the law guaranteeing wages “during a term of fulfilling State or public obligations” (CCE Archive, No. 2).

On 7 July Shcharansky’s wife left for Israel. He himself was refused an exit visa.

*

[10]

In 1974 it became common practice to disconnect the telephones of people who made frequent telephone calls abroad of which the authorities disapproved. This was based on the now effectively legalised system of phone-tapping (CCE 27.12 [23]).

In Moscow Grigory Podyapolsky, Yuly Daniel, Larissa Bogoraz and Ludmila Alexeyeva have all had their telephones disconnected. So have the following activists in the Jewish emigration movement: Vladimir Slepak, V. Prestin, Mikhail Agursky, A. Voronel, Victor Polsky, V. Rubin and E. Smorodinskaya. Some of those ‘disconnected’ were informed that their telephones were being cut off for six months.

Since December 1974 all Andrei Sakharov’s telephone calls to and from abroad have been disrupted.

*

[11]

On 24 June 1973 A. O. Smirnov, nephew of the late writer Alexei Kostyorin, was ‘cautioned’ under the 25 December 1972 Decree. Smirnov is a manual worker at ZIL, the Likhachov motor-works factory, and a 3rd-year student at the ZIL factory’s higher education and training school. He did not sign the ‘record of caution’.

*

[12]

SNAKESKIN CONFISCATED

On 25 June 1974 eight people were taken to KGB headquarters in Tbilisi:

- Maia Diasamidze, assistant producer at the Youth Theatre;

- Pikria Makalatia, research worker, Tbilisi University toponomic laboratory;

- Liya Kazakhashvili, an employee of the Micro-Electronics Institute;

- the philologist Zeinab Lomdzharia;

- Eteri Goksadze, proof-reader on the journal Tsiskari;

- Marine Machavariani, research assistant, Tbilisi University faculty of philosophy;

- Marina Gogoladze, a guide at the Tveriya hotel; and

- the surgeon Vakhtang Khutsidze.

They were interviewed by Colonel Zardalishvili, deputy chairman of the Georgian KGB.

Duplicated copies of the book Snakeskitu [1926] by Georgian writer Robakidze, produced on an Era duplicating machine, were confiscated from the detainees. Robakidze is a well-known Georgian émigré writer. He wrote in three languages: Georgian, Russian and German. The action of the novel Snakeskin takes place before the 1917 Revolution. (Not long ago, Robakidze was called a ‘fascist’ in the official newspaper Kommunisti.)

Those detained were made to promise in writing that this would never happen again. The detainees were asked whether they also read Solzhenitsyn.

In connection with this case, Givi Nebieridze, the head of the Cybernetics Institute photography laboratory, and two laboratory workers, Mikiashvili and Nadtsvilishili, were suspended from their jobs.

*

[13]

At a meeting of Komsomol activists from various university laboratories on 27 September 1974 the secretary of the Moscow University Komsomol committee stated that the university’s Party committee had decided to dismiss anybody who told political jokes.

In addition, he said that the Party organization knew that the book Gulag Archipelago was being passed round among the staff at the university. He expressed the view that anybody, and especially a Komsomol activist, who discovered a copy of this book should immediately hand it to the Party authorities: “Put it on this table five minutes after you see it,” he said.

*

[14]

KVACHEVSKY

After his release from a camp in 1972 Lev Kvachevsky (CCE 27.12 [3]) was forced to live far away from his wife and children; he was not given a residence permit in Leningrad, where his family lived.

In May 1974 he declared that he refused to accept the restrictions on his passport and moved to live with his family. In September 1974 he was summoned to the headquarters of the KGB administration for the Leningrad City & Region: he was told they were aware of his difficult position with regard to work and residence permits, and said they were ready to help him, if he agreed to become their ‘consultant’.

The KGB’s aim was prophylaxis, Kvachevsky was told, not arrests: “Every person convicted is a failure on our part.” Kvachevsky firmly refused. He was then ‘cautioned’ under the 25 December 1972 decree. The text of this ‘warning’ did not contain any concrete charges: it was, fact, a reformulated version of Article 70 (RSFSR Criminal Code).

On 27 December 1974, Kvachevsky left the USSR.

*

[15]

In November 1974, Yefim Grigorevich ETKIND left the USSR (CCE 32.17-3).

*

[16]

In December 1974 Victor Polsky, who was active in the Jewish emigration movement and had long been a ‘refusenik’, was finally allowed to leave the USSR.

*

[17]

KUDIRKA

CCE 33.8 has already reported the sudden pardoning of Simas Kudirka and his emigration to the USA.

Additional details have become known about how Kudirka was handed over by the American captain (CCE 20.6). It turns out that the captain of the Soviet ship sent the American captain a ‘naval protest’ stating that Simas Kudirka had broken into his ship’s safe and stolen 2,000 roubles. Later, during the pre-trial investigation and trial, this charge and the ‘naval protest’ were never mentioned.

With the permission of the American captain a group of Soviet sailors dragged Simas Kudirka off the American ship by force; the American sailors turned their backs on Kudirka’s desperate resistance, and watched television.

*

[18]

On 20 December 1974, Vladimir Dremlyuga (CCE 3.3, CCE 32.19), who participated in the Red Square demonstration of 25 August 1968, left the USSR.

*

[19]

In September-October 1974 Natalya Gorbanevskaya, who took part in the Red Square demonstration of 25 August 1968 [3], received an invitation from a French friend to visit her for a year, and applied to the Visa & Registration Department (OVIR) for permission to do so.

Sometime later, she received a telephone call from OVIR, who asked her to change her application to a request for a permanent emigration visa. Gorbanevskaya did this. On 19 December 1974 she was refused an exit visa, by telephone, with no reasons being given.

*

[20]

YANKELEVICH

On 20 December 1974, Academician Sakharov received a letter threatening reprisals against his son-in-law Efrem Yankelevich and his one-year-old grandson if Sakharov continued his ‘unpatriotic’ behaviour.

The letter was signed ‘The Central Committee of the Russian Christian Party’; in addition to the letter the envelope contained a cutting from a 19 December newspaper featuring the well-known TASS statement and Gromyko’s letter to Kissinger.

The day before, 19 December, Efrem Yankelevich and his wife Tatyana Semyonova were refused exit visas to the USA for a year’s residence there at the invitation of the President of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. They had submitted their application in spring 1973. They were also told, “Our superiors have instructed us to inform you: you may submit an application for permanent emigration to Israel.”

Sakharov reported the threatening letter to the police, but so far the police have not reacted in any way — no one has even come to examine the original letter.

*

[21]

The February 1974 issue of the journal Young Communist was removed from circulation in connection with its publication of “The Alternative”, an article about Alexander Herzen by A. L. Yanov. The editor and the author [4] were summoned for ‘a chat’.

*

[22]

In August 1974 the name of Yu. Mikhailov disappeared from the list of songwriters on the posters and programmes of the Moscow Komsomol theatre. Mikhailov’s name has now reappeared on the theatre’s posters.

*

[23]

As revealed in a ‘secret letter’, read at closed Party meetings in Georgia, more than 25,000 people have been arrested in the republic over the last two years in the course of the anti-corruption campaign [5].

Among them were 9,500 members of the Communist Party; about 7,000 Komsomol members; and about seventy officials of the police and the Security Service.

*

[24]

In Lithuania the latest issues (Nos. 11-13) of the Chronicle of the Lithuanian Catholic Church have appeared.

*

[25]

Khronika Press (New York) has published the following:

- A Chronicle of Human Rights in the USSR (CHR), issues 9 & 10;

- A Chronicle of Current Events (No. 28); A Chronicle of Current Events, Nos 28-31 in a single volume;

- Sakharov’s essay “On Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s ‘Letter to Soviet Leaders’,” and

- Valery Chalidze’s book Human Rights and the Soviet Union.

*

[26]

On 27 July 1974 Yekaterina Lvovna OLITSKAYA died.

In the 1920s, before her first arrest and between her first and second arrests, Olitskaya was an active member of the Socialist Revolutionary Party (the SRs). She spent the 1930s and 1940s in prison and exile.

Her book My Memoirs has been published in samizdat and abroad. There is an obituary of her in A Chronicle of Human Rights (CHR), No. 10.

*

[27]

Made in the USA

On 26 May 1974 the electricity meter was replaced at 32 Ageyev Street in Tula (south-central Russia), the home of Gennady Konstantinovich KRYUCHKOV [6], chairman of the Council of Churches of the Evangelical-Christian Baptists.

*

On 8 June Yury Kryuchkov, G. K. Kryuchkov’s brother, opened the meter at the request of Gennady’s wife Lidiya Vasilievna and examined it. At first he found nothing. Then he tried to undo two screws which attached the meter’s mechanism to the outer casing. The screws turned out to have two heads, however: although the outer casing came off, the screws remained in place.

Then Yury Konstantinovich took the meter off the wall and, by carefully examining it, noticed some barely visible slits in the screws. Inserting a needle into these slits, he managed to unscrew the casing and take out the meter’s mechanism. Behind the mechanism, instead of the back part of the casing, he found a black steel plate concealing a microphone. The microphone was directly connected to the circuit in the meter itself, and a miniature microphone monitor was taped to the back part of the casing. On the monitor was written in English ‘Made in the USA’. The other equipment had Soviet markings.

The meter was taken down and opened between 12.0 noon and 1.0 p.m. on Saturday 8 June. Immediately the house was surrounded by ‘people in plainclothes’. Soon two men calling themselves electricians entered the house. Seeing the opened meter, they made a written report and turned off the lighting.

*

From the moment the meter was opened, everyone coming out of the house was detained, searched and interrogated.

In addition S. F. Selivanov, an Investigator from the Tula City Department of Internal Affairs (UVD), kept demanding of Kryuchkov’s wife, “Return to us what you found”. At times he resorted to threats: “Watch out! The case isn’t closed! After all, that equipment was expensive — you’ll answer for theft.”

Lydia Kryuchkova has written an Open Letter ‘To all Christians of the Evangelical-Baptist faith’, offering an account of these events and including a photograph of the open meter and the microphone.

============================================

NOTES

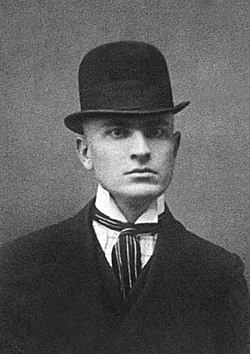

Feature photo is of the Georgian novelist Grigol Robakidze [item 12] as a young man.

*

- A month earlier, KGB deputy chairman Tsvigun (27 August 1974*, 2436-Ts) informed the Central Committee that his organisation and the Procurator-General’s Office had applied for both Yakir and Krasin to be released early, in view of “their penitence, press conference and good behaviour in exile”.

↩︎ - Compare CCE 4.4, “Sentenced for Betraying the Motherland”.

↩︎ - On Natalya Gorbanevskaya, see August 1968 letter (CCE 3.3), 1970 trial (CCE 15.1), 1972 release (CCE 24.11 [11]) and Name Index.

↩︎ - The author Alexander Yanov (1930-2022) emigrated to the USA in 1975.

↩︎ - See CCE 34.13 on corruption in the Georgian Orthodox Church.

↩︎ - Gennady Kryuchkov has been sought by the authorities for some years, but as of early 1977 he was still apparently eluding them.

↩︎

Grigol Robakidze (1880-1962)

============================