From 23 June to 1 July 1977 the trial of the writer Mykola Danilovich RUDENKO, head of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group and a member of the Soviet Group of Amnesty International, and Oleksiy Ivanovich TIKHY (Ukr. Tykhy), a Helsinki Group member, took place in the Donetsk Region (east Ukraine), in the town of Druzhkovka [1].

Both men were arrested on 5 February 1977 (CCE 44.4).

*

TRIAL

The case was heard in an assizes session of the Donetsk Regional Court.

The court chairman was E.N. Zinchenko, deputy chair of the Regional Court; the prosecutor was Procurator Arzhanov from Kiev; the court-assigned defence lawyers were F.I. Aleksevnin (for Rudenko) and Koretsky (for Tikhy). Tykhy refused the services of the lawyer assigned to him and more than once during the trial he reiterated this refusal. In spite of this, Koretsky took part in the trial.

Rudenko (b. 1920) was charged under Article 62, pt. 1 (UkSSR Criminal Code = Article 70, RSFSR code). Tikhy (b. 1927) was charged under Article 62, pt. 2 & Article 222 (“illegal possession of a firearm”).

Article 62, pt. 2, was applied to Tikhy on the grounds that he had already served seven years’ imprisonment from 1957 to 1964 for “Anti-Soviet Agitation & Propaganda” (this issue, CCE 46.21). Article 222 related to an old German rifle which was found at his home during a search in December 1976 (CCE 43.7 [10]).

The case materials filled 47 volumes.

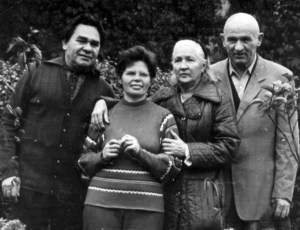

(l. to r.) Mykola Rudenko, Raisa Rudenko,

Zinaida Grigorenko, Pyotr Grigorenko (1970s photo)

*

Rudenko’s and Tikhy’s relatives first learned of the trial on 25 June from summonses issued to “witnesses for the defence” (Raisa Rudenko, Ivan Kandyba and others) to appear at 10.00 on 28 June. They arrived in Druzhkovka on 27 June. However, the chairman of the Druzhkovka town people’s court, N.A. Ladyzhsky, refused to inform them where the trial was taking place: “Come again tomorrow morning at 10.00 and I’ll give you the address.”

Nonetheless they were themselves able to find the location of the proceedings. The trial was taking place in the ‘Red Corner’ of the office of the General Trading organization. The sign bearing the name of the office had been removed.

They were not allowed into the courtroom: “There are no free places!” On 28 June Rudenko’s sister, Tykhy’s 80-year-old mother, and his two sons (one of whom had learned of the trial from the radio) were allowed into the courtroom. Tykhy’s sister was not admitted: “The judge forbids it!”

Pyotr Vins and a friend of his were removed from a bus coming from the city of Donetsk. They were taken to a police station, where police searched them, took their money, bought them tickets, put them on an aeroplane, and sent them to Kiev. On 28 June Pyotr Starchik and Kirill Podrabinek came to Druzhkovka from Moscow. Both were taken to the police station “for identification”. Starchik was threatened with ‘a madhouse’ and sent back to Moscow the next day. Podrabinek was released only on 1 July, two hours after the end of the trial. Others who wanted to get into the courtroom were likewise taken to the police station. The ‘public’ who filled the courtroom every day in an organized manner stayed in a hotel.

At night time the defendants were taken in ‘Black Marias’ back to Donetsk, about one hundred kilometres from Druzhkovka.

Raisa Rudenko tried to submit to the court a statement about the violation of the defence rights of her husband: a public lawyer had been assigned to him; she had not even been informed of the termination of the investigation; she had thus been deprived of the possibility of hiring a lawyer of her choice. Her statement was not accepted.

*

EVIDENCE AND WITNESSES

During the course of the trial the defendants requested that the documents used to incriminate them be read out, in particular:

- the “Declaration on the Creation of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group” and

- the Group’s Memorandum No. 1 (CCE 43.6 [2]), and

- Memoranda Nos. 2 & 3 (CCE 45.19-2 [15]);

- the Open Letter of Boris Kovgar [2], and

- the letter of Josyp Terelya to KGB chairman Yury Andropov (CCE 45.14).

The court refused them. Regarding the letters of Kovgar and Terelya the judge said that their authors were mentally ill and for this reason their letters would not be read out.

*

Excerpts from the record of an interrogation of Yury Orlov (CCE 44.7) were read out in court. Rudenko asked that the supplements to this record also be read out. The court refused this petition, too.

*

The testimony of Myroslav Marinovich (Ukr. Marynovych) was read out: he often visited Rudenko and for the most part they discussed literary themes. It was announced that Nikolai Matusevich had refused to give testimony (CCE 45.7). Rudenko then asked the court to read out the evidence which Matusevich and Marinovich had given after their arrest.

Witnesses who were members of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group should know about this evidence, he said, as it was slanderous, provocative and terrifying: the Ukrainian Helsinki Group was not a public group, it stated, but an underground anti-Soviet group (for this evidence, see below).

The judge forbade discussion of the subject, saying that the defendants were not charged with membership of the Group.

*

The court also refused all of Tikhy’s petitions [3].

In court Professor I.I. Stebun, head of the Literary Theory Department at Donetsk University, said that Tikhy had expressed views on the nationalities question, in a conversation with him, which were hostile to our (i.e. Soviet) ideology and had slanderously stated that Ukrainian culture was dying in our country and the Ukrainian language was disappearing. In Stebun’s opinion Tykhy’s articles (see below) had a hostile, slanderous tendency and libelled Soviet reality. Stebun stated that Tykhy hated the Russian language.

The judge asked Tykhy why he had studied at Moscow University if he hated the Russian language. This showed that exactly the opposite was true, Tykhy replied.

Rudenko asked Stebun: “Do you remember, Ilya Isaakovich, how in 1949 they accused you of cosmopolitanism, and what my attitude to this was?” Stebun replied that Rudenko, then secretary of the Party organization of the Union of Writers of Ukraine, had indeed spoken out in defence of writers [4].

The judge struck out at Tykhy’s question to Stebun, “And do you remember how in 1939 you wrote in an article that for Rylsky and his like there was no place in Ukraine, but only in Siberia?”

“Who gave you my article to review?” asked Tykhy. Stebun replied: “The KGB.”

Regarding his conversation with Stebun, Tykhy stated: “You have slanderously asserted that I came to change your views with the goal of drawing you into hostile activities. But there was no discussion at all about conflict between the Russian and Ukrainian cultures”. Tykhy declared to the court: “I accuse Stebun of slander and of denouncing me to the KGB.”

Oleksiy Tykhy (1927-1984)

*

Rudenko had brought a transistor radio with him to the hospital so as to listen to broadcasts by Western radio stations, said A.V. Rusakovskaya, section head at the psycho-neurological hospital where Rudenko was under examination from January to March 1976. But she had taken the radio from him, she told the court.

The court read out testimony by former soldier V.V. Balan, who was in hospital the same time as Rudenko. Referring to what he had been told by two other patients, Balan reported that Rudenko had listened to Western radio stations and had refused to listen to Soviet radio or watch Soviet television, saying that there wasn’t a word of truth in these transmissions.

Raisa Rudenko, Nadezhda Svetlichnaya and Ukrainian Helsinki Group members Ivan Kandyba, Lev Lukyanenko and Alexander Berdnik were also questioned in court as witnesses.

Asked by the prosecutor, “Who was the author of the anti-Soviet documents ‘Declaration’ and ‘Memoranda Nos. 1-3′?” Lukyanenko replied: “All the members of the Group who signed them.”

Raisa Rudenko said in court that the charges against her husband were still not known to her. She considered that by not informing her when the trial opened the court had violated the right of defence. She said that the American lawyer Ramsey Clark had agreed to defend her husband: Judge Zinchenko replied that foreign lawyers have no right to defend Soviet citizens.

At the request of her husband Raisa Rudenko related how on 23 December 1976, the day of the December search (CCE 43.7 [10]), she had, on leaving the house, arranged things in a particular order, and on returning home had discovered that someone had been in the house. “They then came to search us in the evening and showed us 39 [US] dollars which they allegedly found in our home.”

Testimony by Vasily Barladyanu was read out in court: he had given Rudenko his letter to the Procurator of Odessa Region, it said, and Rudenko had acquainted him with “Memorandum No. 2”.

*

PROSECUTION AND CHARGES

The prosecutor’s speech lasted more than two hours.

Procurator Arzhanov said that Rudenko and Tykhy were opponents of socialism, helpers and agents of hostile States, outcasts and traitors to the Motherland who had actively engaged in anti-Soviet activities.

The prosecutor charged Rudenko with the following incidents:

- in 1960 he presented a paper on political economy to the Party Central Committee;

- in 1963 under the pseudonym ‘Fyodorov’ he sent the Party Central Committee a work entitled “The Universal Law of Progress”;

- in 1972 he sent an anti-Soviet open letter to the Party Central Committee;

- in 1974 he distributed his works “The Energy of Progress” and “Economic Monologues” to Sakharov and Turchin, and had written Turchin an anti-Soviet letter;

- in 1975 he wrote an anti-Soviet letter to Sakharov and the story “The First Line”;

- in 1976 he wrote: the novel Orlova Balka; another letter to Sakharov; the works “Gnosis and the Present”, “You Don’t Want to be a Scoundrel — Go to Prison” (about Doctor Kovtunenko, CCE 42.3) and “To People of Good Will”; and a letter to the procurators of Moscow and Kiev.

Rudenko wrote and stored the verses and poems “A Glow Over the Heart”, “Farewell to a Party Card”, “Where Are We?”, “Reply to a Former Friend” and “Before the Opening of the Kanevskaya Hydro-Electric Plant”. He wrote and distributed the narrative poems “History of an Illness” and “Crucifix”.

Rudenko distributed Grigorenko’s foreword to “Economic Monologues”, Alexander Berdnik’s letters of 1972-1977, Boris Kovgar’s Open Letter, Josip Terelya’s letter to Andropov, letters to Vasily Barladyanu and Nadezhda Svetlichnaya, Valentin Moroz’s “A Chronicle of Resistance”, and Ivan Dzyuba’s Internationalism or Russification?

Rudenko prepared, stored and distributed the “Declaration on the Creation of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group” and its Memoranda 1-3.

“Wanting to work more actively against the Soviet regime, Rudenko became friendly with the mentally-ill Grigorenko and in the latter’s flat, as well as in Ginzburg’s flat, he passed documents to foreign correspondents.”

Rudenko gave Ginzburg documents for him to pass to foreign correspondents. Together with Grigorenko he had prepared a letter of appeal to the communists of the USA and Canada.

He had had an anti-Soviet conversation on the telephone with Bohdan Yasen, who was living abroad. Rudenko wrote a letter to Yasen, asking him to help establish contact with the USA consulate in Kiev.

*

The procurator charged Tykhy with his articles: “The Ukrainian Word”, “Thoughts on my Native Language”, “Rural Problems”, and “Reflections on the Ukrainian Language and Ukrainian Language in the Don Region” (these articles were written in Ukrainian); and also with the “Declaration of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group”, its Memoranda 1-3, and “possession of a firearm”.

“The sabotage activities of Tykhy were concealed and planned …,” said the prosecutor. “Tykhy stated that the existence of Russian schools and colleges is a violation of the sovereignty of the Ukrainian State … Tykhy wrote that persons who don’t know the Ukrainian language should not be promoted to leading posts, and he thus sowed hostility between the Russian and Ukrainian nations.”

The prosecutor asked that Rudenko be sentenced to seven years imprisonment in a strict-regime camp and five years in exile. Tykhy should be ruled an especially dangerous recidivist, he said, and sentenced to 10 years in a special-regime camp and five years in exile.

*

DEFENCE

Rudenko’s lawyer Aleksevnin began his speech by saying that he could not deny or contest the fact that his client was guilty.

He asserted that the reasons for the activities with which Rudenko was charged were his personal resentment at having been expelled from the Party and the Writers Union, feelings of dissatisfaction and injustice, his suddenly serious financial position, and the influence on him of Sakharov, Grigorenko, and those fellow-thinkers who had appeared at the trial as witnesses.

Regarding Rudenko’s statement, “I distinguish between the consequences of bureaucratic distortions and the Soviet system itself”, the lawyer said:

“This statement by Rudenko shows that he is not a conservative and is still capable of regaining the correct path, along which he went for a long time and on which he did a great deal for his people and the State.”

The lawyer asked the court to be considerate:

“I ask it to bear in mind that Rudenko is an invalid of the Patriotic War. The blood he spilt on the altar of the fatherland helped to bring victory to our Motherland, Rudenko is seriously ill and such a long imprisonment will have a ruinous effect on his health. I ask the court to show itself as humane and choose for Rudenko the minimum measure of punishment”.

*

Tykhy’s lawyer Koretsky argued in his speech that the charge of “possessing a weapon” had not been proved against Tykhy. The only proof was the rifle which had been found in his home; and witnesses had testified that during the war Alexei Tykhy’s older brother had picked up weapons thrown away by the Germans and had then gone to the front and perished there.

Regarding the charge of “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda” lawyer Koretsky said:

“I am not in a position to say that he is not guilty of this, because his guilt has been proven, although not fully. A crime was committed when Tykhy signed the Declaration and the Memoranda of the so-called Ukrainian Public Group to Assist the Implementation of the Helsinki Agreements. In these documents the Group accuses the government of supposedly having artificially created a famine in the Ukraine in 1933, and uses such terms as ‘genocide’ and ‘ethnocide’, which can be applied only to the Hitlerite Nazis.”

The lawyer also said that it would be illegal to rule Tykhy to be an especially dangerous recidivist, since his criminal record was expunged as of 15 February 1972: the actions with which he was charged related to the time since then. *I ask the court also to take into account the fact that Tykhy is already an elderly man and that he has an aged mother for whom he must care. I ask the court to consider also the reason why Tykhy embarked on this path: because such people as Lukyanenko and others influenced him.”

*

FINAL WORDS

In his final speech Rudenko said:

“… You are not judging me, you are judging the Word, you are judging the universe for being not as the KGB would like it to be.

“Millions of Soviet citizens, writers, scientists have been sentenced because they stated that democracy is absent in our country. For that they have been thrown behind barbed wire. But the Soviet government cannot by these means convince these people that they are wrong … The Russian Tsar Nikolai I was the most savage of tsars, but the way in which he punished Lermontov was to exile him from Petersburg to do service in the Caucasus. Even he did not deal with writers and poets as savagely as happens now in our country …

“I have committed no crime against the Soviet regime. All my activities have been directed against bureaucratic distortions. My entire civic attitude was directed at their removal, not at overthrow of the Soviet regime. I do not regard myself as guilty on any of the charges.”

In his final speech Tykhy spoke about his 1957 ‘case’:

“I consider it incorrect that this court does not even have a copy of the verdict in my first trial. I requested that it be attached to the file of the present case, but they refused me. [CCE 46.21.]

I know the laws, and although I do not agree with some of them, I do not break them … All the charges against me have been invented by the investigators …

“The article ‘Reflections on the Ukrainian Language and Ukrainian Culture in the Don Region’ was sent to an archive, and four months later to the KGB. Why is it that for five whole years I was not charged with this article? Probably because there is nothing illegal in it …

“As for ‘Rural Problems’ it was a draft (which I subsequently scrapped) of a letter to Literaturnaya Gazeta, which had asked its readers to take part in a discussion on this subject …

“The witness Skripkin did not present even one fact. He said only: ‘Tykhy spoke with everyone in Ukrainian.’ Stebun’s ‘notes’ about my essays fall under Article 125 (Ukraine SSR Criminal Code: “slander”). His testimony distorted the course of my conversations and meetings with him …

“There was one phrase in the procurator’s speech which deserves attention: ‘Tykhy associated with people who had been convicted of especially dangerous crimes against the State …’ I consider that there were no criminal activities of any kind. No guilt in the form of direct subversive intent by me has been found. I do not regard myself as guilty on any of the charges.”

*

VERDICT & SENTENCE

On 1 July 1977 the court issued a verdict which repeated in full the demands of the procurator. Rudenko’s typewriter and camera were declared instruments of a crime and were confiscated.

On 4 July Raisa Rudenko had a meeting with her husband in Donetsk.

Rudenko told her that, at first, they had charged him not only with “anti-Soviet agitation & propaganda” but also with Article 64 (UkSSR Criminal Code = Article 72, RSFSR Code: “organizational activities [intended to commit Especially Dangerous Crimes against the State] and also participation in Anti-Soviet organizations”). He stated that he did not believe that Matusevich and Marinovich had given the slanderous testimony ascribed to them: it was a provocative invention of the KGB, he believed.

Rudenko told his wife that harmful testimony against him had been given by Yevgeny Vladimirovich Tsybulsky, who had regularly denounced him to the KGB. The visit was broken off before Rudenko was able to recount the substance of these denunciations.

***

PROTESTS

On 2 July a protest entitled “The Trial of Rudenko and Tykhy: Ten Years of Prison, Ten Years of Torment for Attempting to be a Citizen” was made public by members of the Moscow Helsinki Group (Pyotr Grigorenko, Malva Landa, Vladimir Slepak, and Naum Meiman), and by Ukrainian Helsinki Group members (Lev Lukyanenko, Ivan Kandyba, A. Berdnik, Pyotr Vins, Oksana Meshko and Olga Geiko). Twenty-three other people added their signatures to the protest.

*

On 6 July the chairman of the Soviet Amnesty International Group, Valentin Turchin, appealed to members of Amnesty International throughout the world to work for the release of Rudenko and Tykhy.

*

On 13 July Alexander Berdnik sent L.I. Brezhnev a “friendly open letter” in defence of Rudenko:

“An historic evil has been perpetrated in our country and it will have unforeseen consequences unless it is quickly reversed. … The excessively zealous judges have crucified not the Poet but the Eternal True Word …

“Release the Poet! I assure you, the people would even in the future remember this with gratitude!”

===========================================

NOTES

- Early in 1977 Andropov and the USSR Procurator-General recommended (20 January 1977, 123-A*) that Rudenko be arrested and charged under Article 62 (UkSSR Criminal Code = Article 70 of the RSFSR Criminal Code), but that the investigation “should be conducted not in Kiev, but rather in Donetsk, for which there are procedural grounds.”

↩︎ - For the Open Letter of former KGB informant Boris Kovgar, see CCE 28.7 [2], CCE 30.9, CCE 39.3.

↩︎ - On Tikhy, see CCE 41.5 [5], CCE 43.6, CCE 43.7 [10], CCE 44.4 and Name Index.

↩︎ - This is a reference to the anti-Semitic campaign of the late 1940s and early 1950s against rootless “cosmopolitanism”.

↩︎

=======================