See “Sakharov in Exile”, January-April 1980

parts 1 (56.1-1) and 2 (56.1-2)

*

On 4 May 1980, Andrei SAKHAROV completed an article in Gorky entitled “An Anxious Time” (13 pages):

“I wish to express several thoughts I have about questions that are worrying me as they appear to me here in the depths of the USSR, in a city closed to foreigners where I live under the vigilant surveillance of the KGB.”

The article consists of four sections: 1. International Issues. 2. Problems of the West. 3. Repressive acts in the USSR: Reflections on our Internal Problems. 4. About Myself.

In the third section Sakharov writes:

“The defence of human rights has become a universal ideology, uniting people of all nationalities and the most varied beliefs on the basis of humanitarian concerns …

“In the USSR the human rights movement in its present structure took shape by the end of the 1960s, when the first issue of A Chronicle of Current Events appeared. At the same time the first appeals of the Action Group made their appearance. The human rights movement has no political goals … publicity is its only weapon. Its ethical commitment to non-violent methods is tremendously important.

“I am convinced that nationalistic ideology, even in its more humane and apparently ‘dissident’ forms, is dangerous and destructive …

“‘The Party and People are One’ is a slogan which adorns one building in five. It is not completely meaningless. Yet it is from this very People that defenders of human rights have emerged.

“And they have had their say, which will not be forgotten, because moral strength and the logic of historical development are behind them. I am also convinced that their activities will continue, in some form or other, and with some or other intensity. The important point is not the arithmetic but that the psychological barrier of silence has been breached …

“We are living now through difficult, troubling times, made worse by international tension and Soviet expansion, and still worse things are threatened.

“And inside the country? We face times of heightened oppression.”

In the section ‘About Myself’ Sakharov writes:

“There is no telephone in the flat, and I cannot call Moscow or Leningrad from the post office — the call is immediately cut off on orders from the KGB agents who follow me all the time.

“I receive very few letters, mainly those which attempt to ‘re-educate’ me or simply abuse me: it’s interesting that some of these letters come from the West. Sometimes postcards arrive from the West, however, with kind words and I’m very grateful to the people who write them.

“Once I was escorting my wife’s mother to Moscow and KGB agents with guns in their hands dramatically barred me from entering the train …

“When my wife and I wish to listen to the radio we have to walk the streets at night with a transistor — and while we are ‘walking’ in this way, agents enter our flat, ruin a typewriter or a tape-recorder, and rifle through our papers.

*

“In April [1980], the President of the New York Academy of Sciences, Doctor Lebowitz, visited Moscow.

“He presented Academician Alexandrov, President of the USSR Academy of Sciences, with a demand from American scientists that the authorities revoke my exile and allow me to return to Moscow or, if I should express such a desire, to emigrate to the West.

“Alexandrov replied that exile was in my own interests, since in Moscow I was surrounded by ‘doubtful characters’ through whom State Secrets were being leaked. The answer to the point about emigration was also strange: ‘We have made an agreement not to spread nuclear arms and we are observing that agreement to the letter’.

“I am often asked whether I am ready to emigrate.

“I consider that the prolonged discussion of this question in the press and in many foreign radio broadcasts is inappropriate and inspired by a thirst for sensation. I recognize everyone’s right to emigrate and theoretically I do not make myself an exception, but this question seems irrelevant to me now. The choice is not up to me …

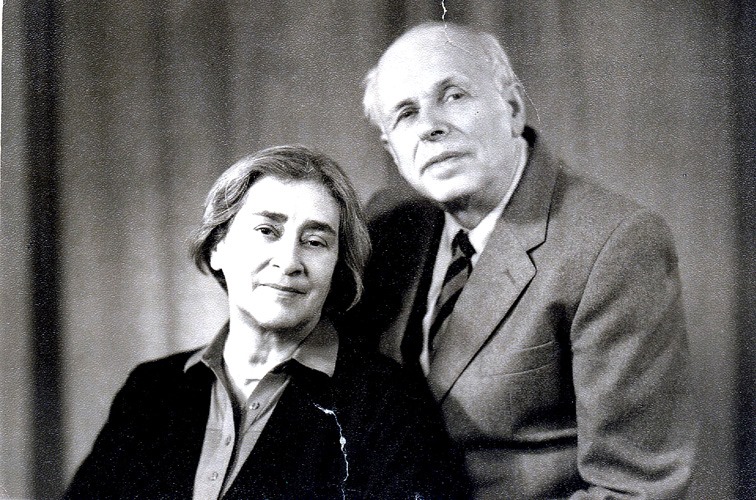

“This article will be taken to Moscow by my wife, my constant helper who is sharing my exile with me and taking upon herself the numerous problems of journeys as my go-between with the outside world. In this way she is earning the ever-growing hatred of the KGB, who both now and formerly have concentrated the poison of their slander and insinuations more against her than me: significantly they have played, for internal consumption, on the fact that whereas I am Russian she is half Jewish.

“A short while ago a man who introduced himself as a KGB official appeared at my wife’s mother’s home at 5.30 am and threatened that if my wife did not stop making these journeys to and from Gorky, and inciting her husband to anti-Soviet acts, they would ‘take measures’.

“Our only defence is publicity and that friends throughout the world pay attention to our fate.”

The article was printed in the New York Times (Sunday Supplement) on 8 June 1980, and reprinted in a number of European newspapers.

*

On 15 May 1980, when Rufa G. Bonner and Liza Alexeyeva last tried to travel to Gorky, Liza was detained at the Yaroslavsky Rail Station in Moscow and taken by force to the station police. Alexeyeva was told that she did not have the right to go to Gorky nor did she have the right to be in Sakharov’s Moscow flat; she must live with her parents.

Since 80-year-old Rufa Bonner was unexpectedly left alone, Anastasia Podyapolskaya (wife of Sergei Nekipelov), who had gone with her and Alexeyeva to the station, was obliged to accompany her to Gorky. At the rail station in Gorky Podyapolskaya barely had time to greet the Sakharovs before she was pulled away from Sakharov and ordered to return immediately to Moscow. Yelena Bonner travelled back with her.

On 16 May 1980, Yelena Bonner issued ‘A Statement for the Press’:

“For over two years Liza Alexeyeva has been a member of our family. She lives with us; we are one household with one budget. In Soviet law that means that we are one family.

“What is the KGB trying to achieve by this new action against our family?

“Do they want my 80-year-old mother to drop dead? Do they want Liza Alexeyeva to commit suicide? Incitement to suicide is a criminal offence (Article 107, RSFSR Criminal Code). May I remind you that over a year ago Alexeyeva did make an attempt at suicide, brought on by what seemed to her the impossibility of resolving the problem of emigrating to be with the man she loves; it was only by chance — because I was at home, gave her first aid, and called an ambulance — that her attempt was not successful.

“Now Alexeyeva is at the mercy of the KGB.

“They have torn her away from our family and, unfortunately, we already know of more than one instance of suicide by people driven to despair by these agencies. At the time we did not publicize what had happened to Liza, out of a desire to smooth her return to normal life. But the KGB crudely used our personal tragedy to accuse Sakharov and myself of immorality and, at the same time, to play on the baser feelings of those readers of the Soviet press who are greedy for every lie, especially when it concerns someone’s private life.”

Bonner is referring to an article entitled ‘Bitter’ in the newspaper Nedelya [The Week] No. 26, 1979, Orlovsky letter (CCE 53.30-1 [10]. The newspaper Gorky Worker reprinted the article on 17 May 1980. (See also the article “Look Behind You, Man” in Nedelya, No. 11, 1980.)

“In relation to Academician Sakharov these actions against Alexeyeva again bear witness that the agents of State Security are willing to pay any price, even the lives of members of our family, in order to isolate him completely, thus making it easier finally to destroy him. Recently only my mother, Liza Alexeyeva and I have had the right to visit Sakharov. In a few days my mother is flying to the USA to visit her grandchildren; yesterday Liza was forbidden to visit Gorky …

“I would also reiterate that Sakharov is still receiving humiliating summonses to go and register at the police station: these are absolutely unnecessary, as a policeman is stationed at the door of the flat day and night. Sakharov has refused to register, as he considers that this, like his exile as a whole, is unlawful. All radio broadcasts are prevented from reaching the house by special jamming, in order to isolate Sakharov totally from information. He is deprived of medical assistance, and his heart condition has deteriorated sharply over the past few days.

“I appeal today to everyone who is trying to defend Sakharov to remember that in defending Sakharov you are forced to take on also the defence of his family. We do not know what else those who hold the law in their hands (but prefer lawlessness and Mafia tactics in their every action), have in store for Sakharov and ourselves.”

In a postscript, she adds:

“I urge the Western media to print and broadcast my statement…, though I almost despair of their doing so.”

On 19 May 1980, Yelena Bonner returned to Gorky.

Only after her departure was Liza Alexeyeva handed a telegram from Sakharov, dated 16 May. In it he asked her to try again to come to Gorky, in the hope that the incident at the station would not be repeated.

*

On 4 June 1980, KGB official Solovyov issued a warning to Liza Alexeyeva “in accordance with the Decree”. According to the ‘text of the warning’ she is said to be meeting with foreign correspondents and giving them libellous information about the situation of the Sakharov family. If she does not stop, criminal charges will be instituted under Article 190-1 (RSFSR Criminal Code).

Solovyov himself visited Sakharov’s flat in Moscow, where Alexeyeva continues to live, the evening before. He handed her a summons which read:

“In connection with an administrative investigation, an agency of the Committee of State Security (KGB) requests you to come in for a chat …

“An official of the State Security agencies”

*

Gorky newspapers have reprinted practically all the ‘anti-Sakharov’ articles from the national press in January and February 1980.

They reprinted both articles from Nedelya (see above) and an article printed in 1973 in the newspaper for emigrants, Voice of the Motherland. Then it was called “A Judas and a Simpleton”. In The Gorky Worker it was titled “The Judases”. Printed in two successive issue of The Gorky Worker on 13 and 14 June 1980: an unknown ‘well-wisher’ left the 13 June number at the door of Sakharov’s Gorky flat.

An Italian newspaper containing an article ‘exposing’ Yelena Bonner (cf //CCE 43) was sent to Sakharov’s Moscow flat from the USA.

*

In May and June 1980, colleagues from the Physics Institute (USSR Academy of Sciences) paid Sakharov two more visits.

*

On 7 July 1980, KGB officials made another secret search of Sakharov’s flat in Gorky.

This time, however, they were caught red-handed. The next day, Yelena Bonner described what happened in a statement entitled “How the ‘Owner’ of the Flat where Sakharov is Lodged Earns her Wages”:

“On the evening of 7 July Andrei Dmitrievich was summoned to the post office near the house where he lives for a telephone call from New York. He ran out of the flat and I went with him. The telegram announcing the call had been sent from Moscow at 11 am, but arrived at the post office only at 7.30 pm, i.e. at the exact time that the call was scheduled to be put through.

“I stayed with Andrei for several minutes and then went back for some cigarettes. As I entered the flat, I saw two men: one was rifling through papers and the other was in the room where we sleep.

“I could not see what the second man was doing. I started screaming wildly. They took fright and made a dash for the room of the so-called owner. It was only then that I noticed that her door, always locked, was open. They slammed the door, but in their haste they must not have turned the key properly and I managed to open the door in time to see the second of them jumping out of the window. In their haste they had half-overturned the divan and there were still bits of dirt from their shoes on the window-sill.

“I ran into the room, from which the ‘support point’ can be seen. Someone in uniform was standing on the steps; they ran past him, stopping for an instant, apparently to say something. I ran into the lobby and called the policeman who was on duty at the door. The policeman came back with me to the flat and very nervously looked at the traces of the men who had only just run away.

“He then went to the support point to summon the chief. When he returned, however, he said that none of this had anything to do with him. I gained the impression that the policeman had not known what was going on behind the closed doors of the flat, and that in the support point they had assured him that it was not his problem. I left the flat open and went back to Andrei at the post office. By this time, he had been told that the Moscow-Gorky line was out of order and the call would not take place.”

“It is now clear”, writes Bonner “what the flat owner’s ‘work’ consists of”:

“She leaves the window of her room unfastened and goes out.

“People coming to make a secret search climb in through the window; they have a key to her room, they open the door and then they have the run of the flat; the policeman standing at the door does not even suspect what is going on inside. On the whole the ‘owner’ is earning her wages!

“Yet this is not just a case of secret searches, which have been a fact of life for a long time. Where is the guarantee that, when these Gorky gangsters are bored with reading Sakharov’s papers, they won’t find themselves a more ‘interesting’ occupation inside the house: adding something to the food in the fridge, putting a pillow over the face of someone asleep, or…”

Yelena Bonner sent a telegram to Alexandrov, President of the USSR Academy of Sciences:

“The entry of KGB officials into the flat without the knowledge of the police guard constitutes a direct and real threat to the life of Academician Sakharov.

“I am asking you to intervene to defend the life and safety of a Member of the Academy of Sciences.”

Bonner sent similar telegrams to the USA: to P. Handler, President of the National Academy of Sciences, and to H. Feshbach, President of the National Association of Physicists. On 8 July 1980, Sakharov sent a telegram to Andropov, head of the KGB. Three days later Sakharov was summoned to the local KGB and told that there would be an inquiry.

When the ‘owner’ of the flat next appeared Sakharov told her what had happened. He asked her to give him the key to her room when she went out — otherwise he would not let her back into the flat.

Several hours later she went out without giving him the key. Sakharov put the chain on the door from inside. When the ‘owner’ next returned Sakharov reminded her of his warning and did not allow her into the flat. The policeman who was standing at his post at the entrance to the flat did not interfere. Since then the ‘owner’ has not been back.

*

On 27 July 1980, Sakharov sent an ‘open letter’ to Brezhnev, addressing copies to the United Nations Secretary-General and to the heads of the permanent member-States of the UN Security Council; Bonner delivered them to the US, British and French Embassies in Moscow. In the letter he proposes a (seven-point) programme for a political settlement in Afghanistan and appeals for a political amnesty in the USSR. He concludes as follows:

“For many years now, every one of my public actions has led to reprisals against people dear to me, thus turning them into hostages.

“My son’s fiancée Elizaveta Alexeyeva – he was obliged to emigrate 2 ½ years ago — is now in such a position. She cannot obtain permission to emigrate and be with the man she loves; she is subject to threats, blackmail and libel in the press. It is I, and only I, who should be held responsible for my words and actions (including this letter).

“The practice of taking hostages by any individual or group is intolerable, especially intolerable and unworthy when the State acts in such a way. I repeat my request: help Elizaveta Alexeyeva emigrate.”

=========================================