- 3-1. TRIAL (Kaluga)

- 3-2. Ginzburg’s APPEAL

*

From 10 to 13 July the Kaluga Region Court heard the case of Alexander GINZBURG, charged under Article 70 pt. 2 (RSFSR Criminal Code) [1].

The Court was made up of Presiding Judge A.I. Sidorkov with People’s Assessors S.M. Brandt and N.P. Parshina. The prosecutor was Procurator V.V. Savkin.

Defending Ginzburg was the Moscow lawyer E. A. Reznikova: when the time came for the defence speech Ginzburg dismissed her and spoke in his own defence. Ginzburg’s other defence lawyer, the American E.B. Williams (CCE 44.3), was refused a Soviet visa.

*

Ginzburg was arrested on 3 February 1977 (CCE 44.3). For details of the pre-trial investigation see CCEs 44-49 [2].

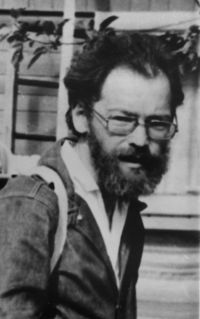

Alexander Ginzburg (1936-2002)

*

Alexander llych GINZBURG was born in Moscow in 1936.

On leaving school he worked as an actor and assistant to a theatre director and as a newspaper reporter. In 1956 he entered the Faculty of Journalism at Moscow University.

In 1959-1960 Ginzburg produced several issues of a samizdat collection of poems by various poets, entitled Syntaxis. He was arrested soon afterwards and sentenced to two years in the camps for forging documents (he had tried to take an examination for a friend). Just before the end of the KGB investigation, Ginzburg was also charged under Article 70 with “Anti-Soviet Agitation & Propaganda”.

In 1962, after his release, having with difficulty managed to settle in Moscow, Ginzburg tried to find a job but met everywhere with official opposition. He worked as a nightwatchman, as a lathe operator, laboratory assistant and librarian.

In 1964 Ginzburg was detained for several days in the Lubyanka. Soon afterwards a letter signed by Ginzburg appeared in Evening Moscow; here he dissociated himself from the sensation created by the Western press around his name. Ginzburg did in fact write such a letter, but the published version differed sharply from the original.

In 1966 Ginzburg became a student at the Historical Archives Institute.

*

FIRST TRIAL (1968)

In January 1967, GINZBURG was arrested for compiling the White Book, a collection of materials on the 1966 trial of A. Sinyavsky and Yu. Daniel [3].

In January 1968 he was tried together with Yu. Galanskov, Vera Lashkova and A. Dobrovolsky (CCE 1.1). He was sentenced under Article 70 pt 1 (RSFSR Criminal Code) to five years in a strict-regime camp: he served his term in the Mordovian camps [4] and Vladimir Prison.

In 1972, having served his sentence, he was released.

He was not permitted to live in Moscow and was forced to settle in Tarusa (CCE 24.11 [10]). In the years that followed he was subject to continual harassment. Twice he was placed under surveillance, and he was often refused permission to go to Moscow to visit his mother, wife and children. It was made difficult for him to find a job, and at the same time he was threatened with charges of ‘parasitism’.

From 1974 onwards, Ginzburg was the official treasurer of Solzhenitsyn’s Relief Fund for Political Prisoners. Ginzburg has belonged to the Moscow Helsinki Group from the moment it was founded.

*

A.I. Ginzburg is married to Arina Sergeyevna ZHOLKOVSKAYA.

Ginzburg’s arrest in 1967 took place five days before the planned registration of their marriage. After the trial Ginzburg and Zholkovskaya tried to obtain permission to register their marriage. Their request was supported by many of Ginzburg’s friends in camp, and five political prisoners declared a hunger-strike (CCE 8.8).

The hunger-strike lasted 3-4 weeks and ended in victory: on 21 August 1969 the marriage was registered in the camp guardroom.

Ginzburg has two sons, aged five and three years.

*

THE 1978 CHARGES

The legal proceedings were based on three themes:

- Possession and dissemination of literature;

- Participation in the compiling of documents;

- activities as treasurer of the Relief Fund for Political Prisoners.

*

1. Possession and Dissemination of Literature

According to the indictment, Ginzburg possessed and disseminated the following works: The Gulag Archipelago and The Oak and the Calf by Solzhenitsyn; the collections Sakharov Speaks and From Under the Rubble; the journals Kontinent and Herald (Messenger) of the Russian Christian Movement [Vestnik RKhD]; several issues of A Chronicle of Current Events and A Chronicle of Human Rights in the USSR; Conquest’s book The Great Terror; Fischer’s Life of Lenin; and Shipwreck of a Generation by Joseph Berger.

The charges in this part of the indictment were based on (a) material confiscated during searches (CCE 44.3) — of Ginzburg’s home in Tarusa and the Moscow flats of his wife Arina Zholkovskaya and his mother Ludmila Ginzburg — and on (b) testimony by the following witnesses:

- A. Gradoboyev: lived in Tarusa, four previous convictions for embezzlement, forgery of documents and pornography;

- V. Podobailov: a citizen of Kemerovo (west Siberia) and an electrician; hearing about Ginzburg on foreign radio broadcasts, he travelled especially to visit him;

- T. Davydovich: a woman friend of Podobailov;

- S. Khanzhenkov: former political prisoner living in Minsk (CCE 46.5-1);

- I. Ivanov: worker living in Tarusa;

- P. Novikova: Ivanov’s sister;

- Victor Pestov: former political prisoner (CCE 45.12) now living in Sverdlovsk (Urals);

- V. Vaganov: acquaintance of Pestov;

- M. Khvoshchov: artist from Tarusa;

- A. Shemetov: writer and member of the Soviet Writers’ Union; lives in Tarusa;

- Victor Kalnins: former political prisoner (CCE 42.3 [12]).

Witnesses V. Podobailov and S. Khanzhenkov insisted that they themselves had asked Ginzburg for books, but Ginzburg had refused to give Khanzhenkov any.

Witnesses V. Vaganov, T. Davydovich, A. Shemetov and P. Novikova testified that they had not received their books from Ginzburg; moreover, the first two were not acquainted with Ginzburg.

Victor Pestov and Victor Kalnins were not present in court, the former due to illness; the latter left the USSR in May 1978. Their testimony during the pre-trial investigation was read out, despite the fact that Kalnins, in a letter sent to the Kaluga KGB in April, had renounced all his testimony.

*

Ginzburg himself stated that the criminal nature of the literature he was charged with disseminating must be demonstrated in court. Otherwise, he said, he would not answer a single question containing the phrase ‘anti-Soviet literature’.

The court read out KGB reports which described the activities of the publishing houses Possev (Frankfurt) and YMCA Press (Paris) as anti-Soviet. Ginzburg said that he was grateful to these publishing houses for printing information on the contemporary situation in Russia and refused to answer further questions about giving books to various people.

The Judge asked why five copies of one issue of the Chronicle of Current Events were found during a search of his home? Ginzburg replied that he constantly used the Chronicle in his work for the Fund, and since the periodical was always confiscated during searches, it was necessary to have not five, but ten copies.

*

2. Participation in Compiling Documents

The incriminating documents were a variety issued by the Moscow Helsinki Group

- 3 : conditions in camps and prisons;

- supplement to 7 : dock strike in Riga;

- 8 : abuses of psychiatry;

- 13 : emigration for economic and political reasons;

- 17 : plight of political prisoners who were ill;

- “An Evaluation of the Influence of the CSCE [the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe] with Particular Reference to Human Rights in the USSR”

- “Acts of political repression at Christmas”.

Also the collection Leave, O my People (about the Pentecostalists), and three letters sent to the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet and the UN Commission on Human Rights.

All the above-mentioned documents were described in the indictment as slanderous.

*

At the very beginning of the trial, even before the reading of the indictment, Ginzburg submitted a large number of petitions.

He requested that additional witnesses should be called; and a number of documents, indispensable to his defence, must be appended to the evidence.

These documents included

- the collected current decrees of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD) governing the situation of prisoners,

- documents concerning the norms and quality of food in places of imprisonment,

- extracts from the verdicts and personal files of prisoners,

- also numerous letters from prisons and camps, confirming the information in MHG Document 3;

- an extract from the verdict in the case of J. Varna and others,

- copies of menus from restaurants in Riga,

- copies of an order about the introduction of a “fish day”, relevant to MHG Document 7 supplement;

- lists of patients and (1971) Directives on the Urgent Hospitalization of the Mentally Ill, relevant to MHG Document 8;

- copies of medical histories and death certificates of political prisoners,

- the archival record of Yury Galanskov’s case (CCE 28.2),

- information on food norms for the sick in camps and prisons, relevant to MHG Document 17.

Not one of these petitions was granted.

The following witnesses were examined in connection with MHG Documents 3 and 17:

- Yury I. Fyodorov [5], Dmitry Demidov (CCE 33.10, CCE 46.10-2) and Dmitry Kranov — all former political prisoners;

- the political prisoners Tyndyuk who worked as a cook in the Perm camps, then as head of the refectory; and Dileyev who was sentenced under a political article in a criminal camp;

- Yu. Fesenko, head of the medical unit at the women’s political camp in Mordovia (penal institution ZhKh-385/3-4);

- Ugodin, director of Vladimir Prison.

(Demidov and Ugodin were summoned to court at Ginzburg’s request, with a request made during the pre-trial investigation.)

*

Witnesses Fyodorov and Demidov confirmed the description of camp conditions given in the Helsinki Group documents.

Dmitry Kranov [6] told the court that he met Ginzburg and Galanskov in the camp hospital. Kranov said he himself had received good medical treatment. He recalled that Galanskov had often been deprived of his right to use the camp shop.

Ginzburg asked the witness how serious he thought Galanskov’s condition was, and whether he was in a fit state to undergo punishment, but the Judge deleted the question, saying that Kranov was not a doctor. (Prior to his arrest Kranov had completed four years’ study at a medical institute). Tyndyuk and Dileyev described camp conditions as acceptable and maintained that food norms were adhered to.

Fesenko and Ugodin testified that conditions in camps and prisons were good. However, Fesenko confirmed the existence of food norm 9b (for those in punishment cells, CCE 33.2). Ginzburg’s question as to the extent of this food norm was deleted by the Judge.

In answer to questions from the defendant and his lawyer, Ugodin asserted that no one was put in a punishment cell for more than 15 days. At the lawyer’s request the court verified the presence in the case file of a document in which it is stated that Vitold Abankin, an inmate of Vladimir Prison, spent 45 days in a punishment cell. 15 days, followed by a break of three days; 15 days, followed by a break of five minutes; then another 15 days (CCE 46.10-1 [24]).

The following witnesses were questioned in connection with the supplement to MHG Document 7:

- Shayekhov — a dock worker from Riga;

- Lerov and Dizhbit — journalists who had written articles denying reports of a strike at the Riga docks.

In court the witnesses stated that there had been no strike.

In addition, Shayekhov said, “There is meat even on fish days,” in the Riga Port refectory, but Lerov stated that there were no fish days at all. Questioned about letters from abroad addressed to Riga dockworkers, which Lerov had mentioned in his article in Ogonyok (No. 17, 1977), Lerov referred the question to Dizhbit. Dizhbit, however, maintained that he knew nothing about these letters.

In connection with MHG Document 8, T.P. Pechernikova, Head of the Medical Examinations department at the Serbsky Institute, and Kuzmicheva, a doctor at Psychiatric Hospital No. 14 (Moscow), were questioned. They stated that abuse of psychiatry did not occur.

No one was questioned in connection with the other incriminating documents.

Ginzburg’s request that Yury Mashkov’s address should be found and that he should be summoned to court to testify that he was the author of letters attributed to Ginzburg, was turned down. (Former political prisoner Yury Mashkov had recently left the USSR.)

When questioned about the “Helsinki Documents” Ginzburg answered that he was the author of the document about the Riga dockers’ strike, and shared responsibility for the rest with all the members of the Helsinki Group; he did not intend to play down the extent of his participation in compiling each document.

The collection Leave, O My People was compiled from Pentecostalist documents. Ginzburg stated that he accepted full responsibility for it, since he had compiled it.

*

3. Ginzburg’s activities as Treasurer of the Relief Fund for Political Prisoners

The indictment stated that, using funds obtained from abroad, Ginzburg had engaged in anti-Soviet activities with the aim of undermining and weakening the Soviet regime. Ginzburg was also accused of using money from the fund to live on.

Witnesses Gradoboyev, Fydorov, Dileyev and Vladimir Tkachov, all former political prisoners, were questioned in connection with this part of the indictment.

Gradoboyev stated that Ginzburg ‘bought information’ from alcoholics in Tarusa, paying them either in roubles or sometimes in money certificates. The defendant had helped Gradoboyev with money, engaging and paying a lawyer for him. In exchange Ginzburg had asked Gradoboyev to visit some Baptists and gather information from them, but Gradoboyev had refused.

Gradoboyev also testified that there existed an illegal organization of dissidents which worked by conspiratorial methods, using self-erasing slates, and that this organization was supported by the West.

*

Witnesses Fyodorov, Tkachov [7] and Dileyev testified that the Fund helped many prisoners and their families unconditionally. Tkachov expressed the opinion that Ginzburg’s activities could be explained by the fact that he wished people to speak well of him “when he next got locked up”. The witnesses did not confirm the allegation in the indictment that Ginzburg lived on money from the fund.

During Ginzburg’s cross-examination his letter to Natalya Solzhenitsyn, confiscated from someone by customs officials, was mentioned. Ginzburg protested against the reading of his personal correspondence in public, but the Procurator read extracts from the letter where Ginzburg stated that the Gulag Archipelago was being widely reproduced and spreading across the country and that he would like to have 30 copies of it.

Ginzburg was asked about the people he had helped. He replied

“Neither your money, citizen Judge, nor the Procurator’s money, nor the KGB’s money formed part of our Fund, so I don’t intend to render account to you. I submit accounts only to the founders of the Fund: I shall not answer any of your questions about it.”

*

At the end of his speech for the prosecution the Procurator demanded that Ginzburg be condemned as an especially dangerous recidivist, but “since Ginzburg has two small children to support and, towards the end of the investigation, he began to give evidence” he demanded a sentence of eight years in a special-regime camp and three years exile.

(By “evidence towards the end of the investigation” the Procurator evidently meant that, towards the end of the investigation, Ginzburg, who for a whole year had refused to talk to his investigators, had made a few statements, including one to the effect that he alone was the author of the supplement to MHG Document 7.)

*

Defence speech and Sentence

In his defence speech Alexander Ginzburg said that he pleaded not guilty.

He did not consider that the literature in question was anti-Soviet, and the court had not demonstrated its criminal nature. All the facts in the Helsinki Group’s documents corresponded to reality and, having studied the materials of the case, he had once again been convinced that this was so. Ginzburg repeated that he did not intend to give the court an account of the work of the Fund, but he considered it necessary to state that he had not used the Fund’s resources for his own personal needs but had lived on his own salary and that of his wife, and on royalties from his book, which had been published in the West.

Ginzburg’s final plea was brief.

He was taking the opportunity, he said, to send greetings to his friends and to express solidarity with Anatoly Shcharansky, who was on trial at the same time. “I understand,” said Ginzburg, “what it means to wait in the death cell for 17 months.” He himself had for 17 months been threatened with charges under Article 64 (Treason), he said, and with the death penalty.

The court found Alexander Ginzburg guilty

- of possessing and disseminating anti-Soviet literature;

- of compiling documents and articles slandering the Soviet system;

- of organizing anti-Soviet activities using money from abroad.

The court found that Ginzburg was an especially dangerous recidivist and sentenced him to eight years in a special-regime camp. According to the verdict Ginzburg also had to pay 1,500 roubles in legal costs.

*

APN Novosti special correspondent V. Lysenkov described the verdict thus:

“… it was established in court that between 1973 and 1977 Ginzburg systematically disseminated anti-Soviet materials received from abroad through illegal channels, or compiled by him personally, materials which advocated a violent change in the political and social system of the USSR.

“Using money from abroad, Ginzburg financed the hostile activities of anti-Soviet elements, including professional criminals and accomplices of the German fascists who had taken part in mass executions of Soviet citizens during the Second World War; he incited these elements to commit unconstitutional acts.”

*

Not all the ‘charges’ on which the KGB had worked for the past 18 months were included in the indictment.

There was no mention of the foreign currency which Ginzburg allegedly kept in his wife’s flat, for example, which was ‘confiscated’ during a search (CCE 44.3). Charges of a purely criminal nature abound in the article by A.A. Petrov (Agatov) published in Literaturnaya Gazeta on the eve of Ginzburg’s arrest, but they were also omitted.

In spring and autumn 1977, the investigative agencies worked hard on the idea of an illegal political organization for which the Fund served as a legal cover (see Gradoboyev’s testimony above, and details of the interrogations of Yu. I. Fyodorov in CCE 46.5-1). Yet there was no mention of such an ‘organization’, either in the indictment or in the verdict.

Later, at the end of 1977, a number of witnesses were questioned with regard to Ginzburg’s activities in the camps in 1968-1970 — establishing illegal links with the world outside the camp, organizing hunger-strikes, etc. In addition, some witnesses were told that Ginzburg had been responsible for the death of his colleague Yury Galanskov. These matters were also not mentioned in court. (For some reason they came up during the trial of Shcharansky: see, in the relevant section, the interrogation of Vyacheslav Platonov).

It should be noted that the investigators did not manage to keep secret their interest in these facts. They were thus discussed in good time by people in various parts of the world.

*

During the investigation and at the trial particular attention was paid to Ginzburg’s moral character.

Although Ginzburg was not formally charged either with using money from the Fund for his own personal needs or of immoral conduct, the Judge and Procurator questioned witnesses in detail as to whether Ginzburg took money from the Fund for his own personal use, whether women came to his home, whether they spent the night there, how many beds there were in the flat, etc. The main witness on this point was, again, Gradoboyev. He told the court that Ginzburg drank a lot of alcohol, and explained in detail what he thought of the defendant’s private life, and of his friends in Tarusa and Moscow.

In his opinion, Gradoboyev said, it was impossible for a man to handle 270,000 roubles (the Fund’s turnover) and not take some of it; neither Ginzburg nor his wife, he emphasized, had jobs. Witness Levashov, head of a tourist centre near Tarusa, also talked of Ginzburg’s ‘parasitism’.

Lawyer Reznikova showed the court her client’s labour book, to counter the charges of ‘parasitism’. Despite this, it was stated in the verdict that Ginzburg was unemployed.

Of the 23 witnesses questioned in court, eight were unacquainted with Ginzburg and the rest knew him only superficially.

Yet the court refused the requests of Andrei Sakharov, V. Pomazov, Valery Ronkin and others, who knew Ginzburg well, to appear in court as witnesses. Numerous statements by political prisoners were also ignored (of these, the names of Vladimir Balakhonov, Sergei Kovalyov, Oles Sergiyenko, A. Safronov, Leib Khnokh, Zinovy Antonyuk and Gabriel Superfin are known to the Chronicle). They asked to be summoned to the trial in Kaluga as witnesses, to give evidence regarding conditions in camps and prisons.

Ginzburg’s own petition that 27 additional witnesses be summoned was turned down.

The witnesses he named included KGB investigators Saushkin, Suchkov, Gaideltsov, Oselkov, Nikiforov, Parushev and Gusev. His reason for requesting them as witnesses, Ginzburg explained, was his desire to show that the investigation had not been conducted objectively, but with the use of threats and blackmail. The Procurator stated that this request had the aim of compromising the investigators.

Fyodorov’s testimony at the pre-trial investigation, said Ginzburg, showed that he had been blackmailed (the court refused to accept this as evidence); witness Podobailov was told that he might “change places with Ginzburg”; while witness Demidov was summoned from the witness room “for an interview with the investigators” immediately before his appearance in court. He was promised “every possible privilege” if he “answered well in court”: Demidov was not interrogated at the pre-trial investigation.

Ginzburg and his lawyers persistently tried to demonstrate the truth and accuracy of the facts contained in the documents with which Ginzburg was charged.

With this aim in view, before the start of the court proceedings, Ginzburg submitted over 80 reasoned requests to call additional witnesses and include in the evidence a number of documents, etc (see above). When the examination of the witnesses was over, he asked for verification of the presence in the case file of 800 documents which had not figured in the trial; he also managed briefly to summarize the subject-matter of many of the documents and to state the reasons why he considered it essential that some of them also be read out. The court refused all Ginzburg’s requests.

Because the requests had been aired in court Ginzburg could demonstrate the existence in the case file of a mass of arguments favourable to the defence.

Several facts refuting the charges came to light during the examination of witnesses, although the questions asked by the defendant and his lawyer were constantly barred by the court. (This happened particularly during the examination of the officials Ugodin, Fesenko, Pechernikova and Kuzmicheva.) None of this was mentioned in the verdict.

On the first day of the trial Ginzburg’s physical condition was already giving cause for alarm.

His blood pressure had risen sharply. He asked the court for permission to submit petitions without standing up: the court refused. A doctor was permanently on duty in an adjoining room. At the end of the three days, Ginzburg felt very unwell; he was given an injection and some medicine, but his condition did not improve. Soon after the trial, at a meeting with his wife, Ginzburg told her that due to dizziness and general weakness he had been unable to deliver the defence speech, lasting several hours, which he had prepared.

Ginzburg’s wife Arina Zholkovskaya and his mother Ludmila Ginzburg were admitted to the courtroom. None of the defendant’s friends and acquaintances, who came to Kaluga every day and stood outside the court building (about fifty people) were allowed in to hear the court proceedings. Neither were Benjamin Tua, a 2nd secretary at the US Embassy, and foreign correspondents admitted to the courtroom. A special representative of the USSR Ministry of Foreign Affairs was present in court, however, and during breaks in the proceedings he informed foreign correspondents about the trial. This information was incomplete and tendentious.

When the trial was over, Judge Sidorkov also talked to foreign correspondents. He told them that Ginzburg’s sentence had been reduced to eight years because (allegedly) he had given evidence against Andrei Sakharov and Yury Orlov. According to Sidorkov, this was mentioned in the verdict: which was not the case.

None of Ginzburg’s friends who had travelled to Kaluga were able to find accommodation in the town’s hotels: for them “there was no room”. His wife and mother, A.S. Zholkovskaya and L.I. Ginzburg, were exceptions.

People waiting outside the court building were continually photographed. They themselves were forbidden to use cameras. One of Ginzburg’s friends tried to take a few pictures, but he was told that the vigilantes objected to being photographed; he was taken to a police station and his film exposed. Former political prisoner Valery Ronkin was detained and taken to a police station to have his identity checked. However, this detention, too, was of short duration. In Moscow Vsevolod Kuvakin was taken off a train. He was escorted to a police station and, after his documents had been checked, was released.

*

DAY TWO

On the second day of the trial, when he was being questioned for the second time, witness Gradoboyev stated that Ginzburg and Zholkovskaya were parasites.

He told the court that dissidents might hire assassins with money they received from the West in order to deal with him, Gradoboyev, and that Zholkovskaya had already threatened him with reprisals. (In fact Zholkovskaya told him: “God will punish you!”).

The Judge invited the witness to make a written complaint against Zholkovskaya so that her illegal activities could be curtailed. (Gradoboyev later did write a complaint.) From her seat in the audience Zholkovskaya asked the court for permission to make a statement concerning Gradoboyev’s slanderous testimony. The Judge told Zholkovskaya to be quiet. Zholkovskaya said that a criminal and a slanderer had been allowed to talk for three hours; she asked permission to explain to the court that Gradoboyev was lying.

The Judge ordered that Zholkovskaya be removed from the courtroom. As she was being taken out, she said:

“This isn’t a trial but a filthy kangaroo court. You wouldn’t let Ginzburg’s friends, or Academician Sakharov, tell you about Ginzburg, but you let a liar do it. You wouldn’t let me or my husband work. I was a Moscow University lecturer and have managed with great difficulty to get a job as a house cleaner, and you call us parasites!“

Ginzburg requested that his wife be allowed to return. The Judge recalled Zholkovskaya and ordered her to apologize and to promise to create no more disturbances. Zholkovskaya asked permission to give her explanation regarding Gradoboyev’s testimony and her own conduct in this connection. She was then once again removed from the courtroom. Despite her written appeals to the court and her telegrams to Brezhnev and Andropov, she was not admitted to the trial either that day or on the following days.

Immediately after this incident, witness Lerov (from his seat) accused lawyer Reznikova of discrediting the Soviet press by her questions. Yet he was not expelled from the courtroom, neither was he called to order, despite the lawyer’s demands.

On the first three days of the trial, the vigilantes, the KGB detectives and the police on duty outside the court building behaved with restraint and propriety. Chance passers-by — citizens of Kaluga — reacted in a neutral fashion to what was happening, or even expressed sympathy for Ginzburg. On the day of the verdict, however, a large group of people appeared, portraying the “indignation of the people”. They shouted insults and anti-Semitic slogans, and provoked Ginzburg’s friends. The “demonstration of popular anger” was carefully organized and kept within prescribed limits. It began and ended as ordered, and no serious incidents were permitted.

*

The Soviet press commented on the simultaneous trial of Anatoly Shcharansky and it was mentioned on radio and television. The mass media remained silent on the case of Ginzburg during his trial.

Only two weeks after the verdict, on 27 July, did the Kaluga newspaper Znamya publish an article by A. Shcheglov, entitled “Poverty of Soul”. A few quotations from this article follow:

“Ginzburg tried every possible means to delay and disrupt the proceedings …

“He submitted countless petitions, he insisted on adding (these are the words used! — Chronicle) new documents to the case. Most of them had no relevance to the charges. The court patiently heard him out, occasionally granted his requests, but refused to allow the proceedings to be side-tracked …

“People like Ginzburg do not have and will not have a place in our society. The citizens of Kaluga who were present at the trial greeted the verdict with applause.”

Several days after the trial ended, Ginzburg’s Bible, dictionaries, Japanese primers, judicial literature, pens, spare glasses and personal clothing were taken from him. The sentence had not yet legally come into force, but he was reclothed in striped prison clothing (i.e., as worn by prisoners on special regime).

On 18 August 1978, the RSFSR Supreme Court examined GINZBURG’s appeal [CCE 50.3-2] and left the sentence unchanged.

*

Early in September 1978, Ginzburg arrived at Camp No. 1 in Mordovia.

*

International public interest in the Ginzburg case far surpassed the usual limits of Western interest in political trials in the USSR.

It is impossible to list here all the letters, statements and protests, and the demonstrations and appeals to official Soviet bodies by committees in defence of Alexander Ginzburg. Many prominent writers, public and political figures, and mass organizations in various countries took part in this campaign. In the USSR itself, Ginzburg’s case prompted hundreds of people, including entire religious communities, to speak out in his defence.

A detailed account of the investigation and the texts of letters and statements are published in Information Bulletins about the case: Nos 1 (CCE 45.4), 2 (CCE 47.18 [10] and CCE 48.25), and 4 (CCE 49.20 [6]).

Immediately after the trial the book Kaluga, July 1978 appeared in samizdat. Material from this book has been used extensively here.

========================================

NOTES

- The sequence of trials — Orlov and the “repentant” Gamsakhurdia simultaneously in May, then Ginzburg and Shcharansky in July — was devised on the recommendation of KGB head Andropov and Procurator-General Rudenko (1 April 1978, 785-A* joint memorandum).

↩︎ - For pre-trial investigation, see CCEs 44-49: CCE 44.3, CCE 45.4, CCE 46.5-1, CCE 47.3-1, CCE 48.2 and CCE 49.6.

↩︎ - Published in English in 1967, edited by Leopold Labedz and Max Hayward, under the title On Trial: The Case of Sinyavsky (Tertz) and Daniel (Arzhak), Harper & Row: New York.

↩︎ - From having special-regime status the camp now had ordinary status.

↩︎ - On Yury Ivanovich FYODOROV, see CCE 42.3 [8], CCE 44.19, CCE 45.13 [2] and Name Index.

↩︎ - Dmitry Nikolayevich Kranov (b. 1946) was arrested in Kuibyshev in 1969; he was sentenced to two years imprisonment under Article 70 (CCE 17.14-2 [12]).

↩︎ - Vladimir Tkachov served 10 years from 1961 to 1971 for “Betrayal of the Motherland” (CCE 22.8 [15]).

↩︎

=============================