This section has been compiled largely from the Information Bulletins of the Working Commission, Nos. 9 (9 June 1978), 10 (10 August 1978) and 11, a special edition about the trial [1].

*

Arrest and Investigation

Alexander Podrabinek was arrested at the flat of some friends on 14 May 1978, the day before the beginning of the trial of Yury Orlov. At the time of the arrest a search was also conducted. Podrabinek was taken to the Investigation Prison of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD) on Matrosskaya Tishina Street.

*

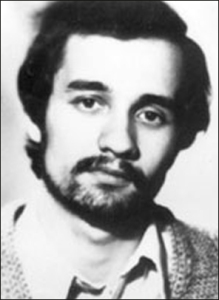

Alexander Podrabinek, b. 1953

*

Alexander Pinkhosovich PODRABINEK was born in 1953 in Elektrostal (Moscow Region). In 1970, after leaving secondary school, he enrolled at a medical institute, but left after a year.

In 1974 Podrabinek enrolled at a college to train as a doctor’s assistant. From 1974 to 1977 he worked in the ambulance service and before his arrest he worked for several months as a paramedic.

Alexander Podrabinek was one of the organizers of the “Working Commission to Investigate the Use of Psychiatry for Political Purposes” [2]. Nos. 44-48 of the Chronicle [3] provide information about the persecution of Alexander Podrabinek.

*

On the day after his arrest another four searches were carried.

The homes of Tatyana Velikanova; of Tatyana Osipova, a member of the Moscow Helsinki Group; of Vyacheslav Bakhmin, a member of the Working Commission; and of Leonid Ternovsky (who became a member of the Working Commission on 24 May 1978) were all seached.

The case against Alexander Podrabinek, as became evident after his arrest, had been opened by the Moscow Region Procurator’s office under Article 190-1 (RSFSR Criminal Code) at the end of December 1977: his elder brother Kirill was arrested at this time (CCE 48.7).

The investigator was V.M. Guzhenkov. Soon after Podrabinek’s arrest Guzhenkov said that the charges against him were connected only with his book Punitive Medicine: CCE 44.15 [4], CCE 45.19-1 [9], CCE 46.5-1 [4].

- On 20 May an Open Letter “To Compatriots and the World Public” (127 signatures) began to circulate. It protested against the arrest of Alexander Podrabinek and called for support in fighting for his release;

- A similar document (No. 51) was published by the Moscow Helsinki Group;

- on 24 May another (signed by Bakhmin and Ternovsky) was issued by the Working Commission;

- On 24 May Pinkhos Abramovich PODRABINEK, father of Kirill and Alexander, issued an appeal “To all People of Goodwill”.

*

On 29 May 1978, Bakhmin was summoned for interrogation.

He refused to answer questions concerning Podrabinek and his book, saying the charge against Alexander Podrabinek was absurd: he considered it immoral to take part in an investigation of the case.

As early as 2 June 1978, Guzhenkov informed Bakhmin, Alexander Podrabinek’s legal representative, that the investigation was coming to a close and it was necessary to engage a defence attorney. Knowing Podrabinek’s wishes in this matter, Bakhmin invited the barrister S. Shalman, who agreed to conduct Podrabinek’s defence.

At the time, Shalman was on holiday and despite his consent to act as Podrabinek’s defence the managers of the legal consultation office refused to call him back. For his part, Guzhenkov did not want to postpone the closing of the case.

*

On 13 June 1978, the investigation of the case of Alexander Podrabinek closed.

On 19 June, the investigative agencies proposed another defence attorney. Podrabinek refused to engage him. In this situation Bakhmin, in accordance with Podrabinek’s wish, invited the British barrister Louis Blom-Cooper QC to defend him at the trial. At the same time L.G. Machkovsky was engaged to help A. Podrabinek study the case materials.

On 21 June Machkovsky began reading the case materials: there were four volumes in all, one of which consisted of the book Punitive Medicine (1977). On 30 June, the document certifying the completion of the study of the case was signed. The case was transferred to a court.

In mid-June, Professor Linford Rees (CCE 49.18 [8]), President of the Royal College of Psychiatrists (United Kingdom), sent a letter to Brezhnev:

“Dear President Brezhnev,

“I have been asked by the Council of my College to write to you to express our members’ concern at reports of the arrest of Mr. A. Podrabinek …

“We hope that you might take a personal interest in this case and ensure that if Mr. Podrabinek is brought to trial the trial is conducted openly.

“The circumstances of this case puzzle us. We realize that the laws of our two countries are different, but it is difficult for us, on the reports we have heard, to understand what Mr. Podrabinek has done that is, in any way, criminal.”

In June 1978, the College set up a Committee to deal with questions of the abuse of psychiatry. An international committee to defend A. Podrabinek was also founded. Its members included, in particular, the British historian Peter Reddaway and the British psychiatrist Gary Low-Beer (CCE 49.18 [8]).

Yury Belov (CCE 48.12) and Mikhail Kukobaka (CCE 43.8), former political prisoners held in psychiatric hospitals whose notes were used in A. Podrabinek’s book, wrote to the Moscow Region Procurator’s Office, asking to be questioned as witnesses in the Podrabinek case; their request was turned down.

Belov was told (not in writing) that Podrabinek’s guilt was already proven and that the investigation had no use for his testimony.

*

On 13 July 1978, a hearing of witnesses testimony in the case of A. Podrabinek, presided over by Blom-Cooper, took place in London.

Nine witnesses [5] spoke. One, in particular, was psychiatrist Yury Novikov [6], a former official of the Serbsky Institute (CCE 46.15 [12]).

Written testimonies and tape-recordings were reviewed [7].

On 15 July, Mikhail Kukobaka proposed to Blom-Cooper that his notes on the Sychyovka Special Psychiatric Hospital (SPH) be added to the file of testimony.

On 20 July, Victor Nekipelov, a member of the Moscow Helsinki Group, sent Blom-Cooper excerpts from Kukobaka’s four letters about the Psychiatric Hospitals in Vladimir and Mogilyov (Belorussia). Nekipelov also requested that his book The Institute of Fools (CCE 42.12 [9]) be used as testimonial evidence [8].

Blom-Cooper announced in London that the Soviet Embassy had promised to issue him a visa for a trip to the USSR. He did not receive the visa in time, however, to attend the trial of Alexander Podrabinek.

On 18 July 1978, an agreement was reached with E.S. Shalman to defend Podrabinek in court.

*

The Trial

The Moscow Region Court examined the case of Alexander Podrabinek, charged under Article 190-1 (RSFSR Criminal Code), on 15 August 1978.

The hearing took place in Elektrostal (Moscow Region) at an Assizes session presided over by R.V. Nazarov, Deputy Chairman of the Moscow Regional Court.

The prosecution counsel was Suvorov, Deputy Procurator of the Moscow Region;

the defence counsel was Shalman.

*

The trial was due to begin at 9 am, but at 6 am the part of the building in which the trial was to take place was already ringed by a cordon of uniformed and plainclothes police.

Alexander Podrabinek’s friends arrived at 8.30 am to be told that there were no places left. “We have already filled the hall in order to maintain order,” a young policeman declared, with provincial naivety. The day before, Vyacheslav Bakhmin appealed to Judge Nazarov, requesting to be admitted to the trial as the legal representative of the accused.

Nazarov expressed bewilderment: it was a normal criminal case, anyone who wanted could be present. The following day, however, Nazarov himself had to stand in the rain and rummage in his briefcase for his pass until a plainclothes man ran out and conducted him through the cordon.

Several minutes before the trial began, the accused’s father Pinkhos Podrabinek and his own wife Alla Khramtsova (she left half-way through the day in order to feed her child and was not allowed back) were admitted to the courtroom. No other relatives or friends of Alexander Podrabinek could get in.

At 10.30 am some of his friends made a phone call to Moscow from the post office, which was located in the same building as the courtroom. After that the connection with Moscow was cut off.

*

At the beginning of the hearing, Alexander Podrabinek submitted a series of petitions to the court, requesting that certain documents be added to the case file:

- Statutes on Psychiatric Hospitals;

- Ministry of Health directives concerning hospital food;

- the international classification of illnesses;

- indictments and psychiatric reports on 30 political prisoners formerly held in psychiatric hospitals;

- reports on the examinations of Pyotr Starchik and Yury Belov carried out by British psychiatrist Gary Low-Beer;

- the medical history of Radchenko and the medical report on his death;

- the post-mortem report on Dekhnich.

Podrabinek also petitioned for the following to be called as witnesses: the psychiatrist Fyodorov, former inmates Yury Belov, Mikhail Kukobaka, and Pyotr Grigorenko; and N.Ya. Shatunovskaya (mother of Olga Joffe — see CCE 11.7 and trial, CCE 15.2 — who was compulsorily interned in the Kazan SPH).

Podrabinek further requested that the following be procured: the two-volume edition of Mashkovsky’s Medicinal Remedies; several copies of A Chronicle of Current Events and the Information Bulletin of the Working Commission; the 1977 book by Bloch and Reddaway on psychiatric hospitals in the Soviet Union; and issues of the Korsakov Journal of Neurology & Psychiatry containing information about the International Congress of Psychiatrists in Honolulu (CCE 47.15 [21]).

Podrabinek also asked the court

- (a) to engage an Italian-Russian interpreter, since the case materials included documents in Italian (materials of the Sakharov Hearings);

- (b) to allow him (Podrabinek) to hear the tape-recordings of his interrogations;

- (c) to call the British barrister Blom-Cooper to the trial as defence counsel; and

- (d) to arrange for the trial to be relayed to all interested.

Podrabinek gave reasons justifying each petition, almost all of which were supported by his defence counsel. The court rejected all the petitions.

*

Podrabinek then announced that he was dispensing with the services of his defence counsel Shalman and would conduct his own defence. After several altercations among themselves the Judge and his lay assessors complied with this petition.

Podrabinek further stated that Articles 18 (“The openness [glasnost] of the court examination”) & 20 (“The comprehensive, full and objective investigation of the circumstances of the case”) of the RSFSR Criminal Procedural Code had not been observed by the court.

The prosecutor (procurator) and the panel of judges adhered to the Communist ideology and were obliged to fulfil the tasks set by the Party in order to keep their jobs. In this sense they were interested parties. On this basis, Podrabinek challenged the whole composition of the court. The court rejected his challenge.

Then Alexander Podrabinek made the following declaration:

“I do not want an illusion of justice. My lawyer is not, in actual fact, in a position to conduct my defence. For this reason I have dispensed with him as my defence counsel at the trial.

“Henceforth, moreover, I shall take no further part in the trial. I do not participate in staged performances of this kind. I have no talent as an actor and therefore shall not take part in this show, even as an extra.

“I demand to be taken from the courtroom.”

The court attempted to ignore Podrabinek’s last demand.

However, he behaved in such a demonstrative manner (smoking and whistling) that when the questioning of witnesses began, the court was obliged to take him out of the courtroom, citing Article 263 of the RSFSR Code of Criminal Procedure. The Judge issued a ruling that Podrabinek could submit a petition at any time and return to the courtroom. Podrabinek immediately stated that he wanted to return when the time came to make his final speech.

According to the indictment:

“Podrabinek A.P…. is charged with preparing several copies of a document entitled Punitive Medicine when he was living in Elektrostal, Moscow Region, and working in Moscow from 1975 to 1977 and circulating it.

“In this book Podrabinek libels Soviet democracy and the country’s domestic policies. He compares the regime in the USSR with totalitarian fascism. He makes assertions about the use in our country of ‘repressive psychiatric measures’, and about the premeditated placing in psychiatric hospitals, for their beliefs, of people known to be sane, and states that they were tortured in psychiatric institutions.

“Podrabinek addressed this document to international organizations and circulated it among his friends in Moscow. The document was used by imperialist propaganda to stir up a campaign of slander against the Soviet Union.”

The indictment cites assertions in the book Punitive Medicine which, allegedly, bear no relation to reality. In the book Podrabinek writes that in July 1975 Anatoly Ivanovich Levitin, a patient in the Sychovka SPH (Smolensk Region, west-central Russia), was killed on the command of Doctor N.P. Smirnov. Levitin was seized during an escape bid. The indictment says: “The case materials, however, have established that there never was a patient of this name in the Sychovka SPH.”

M.M. Fyodorov, chief doctor of the SPH, appearing as a witness at the trial, declared that there had been no instances of murder in the Sychovka SPH and there had been no patient there called Levitin. Speaking immediately after Fyodorov, a junior doctor from the Sychovka SPH, V.V. Moskalkov, said that in 1975 a patient had been killed while attempting to escape. But he could not recall his name.

The book cites a letter written by Mikhail Kukobaka in which he relates that the orderly Sasha Dvorenkov beat patients sadistically at the Sychovka SPH. The indictment says in this respect:

“On page 141 mention is made of a certain Sasha Dvorenkov, who allegedly beat the patients. From the information received from Sychovka SPH it can be concluded that such a person never worked at the hospital.”

Other witnesses questioned in court were:

- V. D. Steshkin, the chief doctor of Leningrad SPH, who said that “normal methods of treatment were used in the hospital; other methods were not used if there was no need for them”;

- Abrosimov, head of the Smolensk SPH;

- T. A. Kotova, a section head of the Oryol SPH;

- F. Svyatsky, former chief doctor of the Chernyakhovsk SPH;

- A, G. Semiryozhko, chief doctor of the Dnepropetrovsk SPH;

Also called as witnesses were V.G. Vvedensky and his wife G. I. Zhabina. After the couple made a report a search was carried out on 14 March 1977 at the flat of Yelena V. Bobrovich (CCE 44.12-15 [4], where the surname was misspelt). It was then that the manuscript of Punitive Medicine first fell into the hands of the KGB.

In the absence of defence counsel and the accused the court questioned the witnesses very quickly.

*

The Procurator concluded his speech in the following way:

“The heaviest sentence possible under Article 190-1 of the RSFSR Criminal Code should be imposed on the accused. Of course, he would very much like the Article to be political. That was why he played out the spectacle we have watched. He thought he would receive seven years under Article 70, but even the degree of punishment has let him down.

“The maximum is not seven, but three years. Considering that this is his first criminal offence and that he is only 25 years old, I request that a sentence of five years exile be imposed, so that he may be re-educated in a labour collective.”

After an adjournment of two hours the sentence was announced: with the application of Article 43 (RSFSR Criminal Code: “mitigating circumstances”), Podrabinek was given five years exile [9].

*

SOPHIA KALISTRATOVA

An Undelivered Speech

A detailed description of Alexander Podrabinek’s trial is given in the 11th issue of the Working Commission’s Information Bulletin.

This also contains Sophia V. Kalistratova’s “Speech not Delivered at the RSFSR Supreme Court during the Review on Appeal of the Case of A. Podrabinek”; Yury Belov’s “Testimony”, which he wanted to give at the trial; Victor Nekipelov’s declaration; and passages from the four letters written by Mikhail Kukobaka (see above).

*

At the beginning of her undelivered speech Kalistratova states:

“The materials to which I have access on the case of Podrabinek give grounds to assert that the laws operating in our country have been violated (and are constantly and relentlessly being violated) from the moment criminal proceedings were instituted against Podrabinek until this day.

“This is no empty assertion and, so far as my strength and resources allow, I shall attempt to confirm what I say.”

The manuscript of Podrabinek’s “Punitive Medicine” was confiscated by the KGB in March 1977 (CCE 44.12-15 [4]). The investigative agencies regarded the text as criminal. They were therefore obliged, in accordance with Article 3 (RSFSR Code of Criminal Procedure), to institute criminal proceedings at once. “Acting outside any procedural norms laid down by law”, however, the authorities put a tail on Podrabinek; and, in an attempt to force him to leave the USSR, they threatened and blackmailed him.

Article 276 of the RSFSR Code of Criminal Procedure states that “all petitions concerning the demanding and verification of evidence relevant to the case should be met without exception”. The court brazenly contravened this law and by rejecting all the accused’s petitions “has completely deprived Podrabinek of the chance to defend himself”.

In particular, the reference to the ‘non-responsibility’ of a number of witnesses whose appearance was requested by Podrabinek was unlawful. Kalistratova explains that neither a person’s non-responsibility, as established by some court in the past, nor the fact of his having been treated in a psychiatric hospital pre-determines his mental incompetence as regards being a witness.

Where there is any doubt, Article 79 of the Code of Criminal Procedure specifies that the court must verify the competence of an individual to appear as a winess by means of an examination.

Article 20 of the Code states that the court must “investigate the moral and ethical sides of the accused’s character”.

“Had people who knew Sasha [Alexander] been questioned, it would have become clear: Alexander and slander are incompatible.”

Despite the real meaning of Article 43 (RSFSR Criminal Code) the court referred to this article in sentencing A. Podrabinek to exile. Kalistratova comments that such a violation, committed for the first time in 1968 at the Red Square “demonstrators”’ trial (CCE 4.1) [Kalistratova was a defence attorney at that trial, Chronicle], is a constant occurrence in political trials.

Involuntarily, Kalistratova notes, the court demonstrated the highly reliable character of the materials assembled by Podrabinek:

“of 300 factual episodes cited in his book only 13 figure in the indictment. Considering the procedural infringements committed by the court, “with regard to these 13 episodes, a lack of correspondence with reality of the facts set out in Podrabinek’s manuscript has not been established”.

The infringements of the law continued after the sentence was imposed:

“According to Article 319 of the RSFSR Code of Criminal Procedure, an individual sentenced to a punishment not involving loss of freedom should be quickly released from custody in the courtroom.

“Yet Sasha Podrabinek was taken back to prison under escort … Moreover, before the period allowed for an appeal had finished, Sasha had already been transferred to the city’s Transit Prison No. 3 at Krasnaya Presnya.

“Article 320 of the Code of Criminal Procedure states that a convicted person held in custody must be given a copy of the verdict no later than three days after it has been read out.

“As of 30 August, I am reliably informed that Podrabinek has not yet been given a copy of the verdict.”

Kalistratova concluded:

“Alexander Podrabinek is a dissenter. In accordance with his convictions, he fought for the rights of the mentally disturbed and those of sane people who for political ends were declared insane. But he is no slanderer. He acted within the boundaries of the law and did not commit a crime.

“The above are the legal grounds on which I base my assertion that the sentence in the case of Podrabinek should be annulled, and the criminal case against him closed, due to the absence of a corpus delicti.”

On 17 August 1978, at a meeting with his father Pinkhos, Alexander Podrabinek said that during the pre-trial investigation he did not sign a single record of interrogation, although Investigator Guzhenkov had tried by using threats to make him take part in the investigation.

The same day Podrabinek was transferred to the Krasnaya Presnya Transit Prison in Moscow.

*

On 16 August 1978, two documents were presented to a press conference for foreign correspondents:

[1] an “Appeal to Foreign Psychiatric Associations” by V. Bakhmin and L. Ternovsky, members of the Working Commission, and

[2] an “Appeal to Psychiatrists Throughout the World” by S.M. Polikanov (CCE 47.8-1), a corresponding member of the USSR Academy of Sciences.

At the same press conference, the previously anonymous consultant psychiatrist of the Working Commission, Alexander Alexandrovich VOLOSHANOVICH stepped into the open. (He works at a psychiatric hospital in the Moscow suburbs.)

At the request of the Working Commission, Voloshanovich related, he had carried out 27 examinations: some of his conclusions have been quoted in the Chronicle (CCE 48.12-1 and CCE 49.10). In not a single case could he find grounds for compulsory hospitalization [10].

*

Not until the beginning of September 1978, was Alexander Podrabinek given a copy of the verdict.

He was not allowed to study the record of the trial until 17 October that year: according to Articles 264 and 265 of the RSFSR Code of Criminal Procedure, this should take place no later than six days after the hearings had ended.

On 23 November 1978, the RSFSR Supreme Court examined Podrabinek’s appeal [11]. The sentence was left as it was. (As previously happened in May, Vyacheslav Bakhmin was dispatched on an urgent business trip at this time.)

============================================

NOTES

Podrabinek was arrested again in 1981, this time in exile (CCE 61.2-1). He was sentenced a second time after an English edition of Punitive Medicine appeared in 1980.

*

- Information Bulletin No. 6 was published in English by the International Secretariat of Amnesty International; No. 11 was published by Amnesty’s British Section.

Nos. 1-5 and 6-9 have appeared in Russian in the Volnoe slovo periodical (Frankfurt, 1978, Nos. 31-32). In all, Nos. 1-14 of the Information Bulletin add up to some four hundred pages.

↩︎ - On the “Working Commission”, see CCE 44.10; CCE 45.14, CCE 47.3-2, CCE 48.12 and CCE 49.10.

↩︎ - See CCE 44.15 [4], CCE 45.10 [2], CCE 47.3-2 and CCE 48.7 for information about the persecution of Alexander Podrabinek.

↩︎ - Published in Russian as Karatelnaya meditsina (Khronika Press: New York, 1979). A 25-page summary was published in English by Amnesty International, International Secretariat in 1977.

A full English edition appeared in 1980 and provided the occasion for another trial. It was held in Yakutia (CCE 61.2) to which Podrabinek had been exiled: he was sentenced to three years in ordinary-regime camps.

↩︎ - The nine were: Yury Novikov, Vladimir Bukovsky, Ludmila Alexeyeva, Marina Voikhanskaya, Gary Low-Beer, P. Sainsbury, Natalya Gorbanevskaya, I. Glezer and Peter Reddaway.

Written or tape-recorded testimony was submitted by Pyotr Grigorenko, Valentin Turchin, Leonid Plyushch, A. Papiashvili, and Sidney Bloch.

↩︎ - Dr. Yury Novikov’s testimony about Soviet psychiatry and its political abuse first appeared, between 22 March and 26 April 1978, in six articles in the West German weekly Der Stern (Hamburg).

↩︎ - Louis Blom-Cooper, Q.C., and his assistant, barrister Brian Wrobel, compiled the evidence and their own commentary in a 54-page dossier. This they sent to the Moscow judicial authorities on 23 July 1978 for inclusion in the case materials, as required by Soviet law.

↩︎ - Victor Nekipelov’s Institute of Fools: Notes from the Serbsky was published in English in 1980 (Victor Gollancz: London).

↩︎ - The sentence provoked protests from a number of medical and other groups, and also from the British government. In particular, the UK Foreign Secretary, Dr. David Owen, deplored it.

Owen’s spokesman was reported as saying on 16 August 1978 that the case was “particularly disturbing”. “[T]he Soviet authorities action appeared to relate to Mr. Podrabinek’s investigation of the misuse of psychiatry for political ends,” he continued. “This was a subject which aroused very strong feelings in Britain and about which Dr. Owen personally was very concerned.”

↩︎ - Copies of 23 of Voloshanovich’s reports are in the possession of the Royal College of Psychiatrists in Britain and other bodies. They are confidential documents. Extracts can be publicly quoted, however, should the examinees in question be forcibly hospitalized or in danger of such hospitalization.

↩︎ - On 22 August 1978, Blom-Cooper and Wrobel sent a 14-page appeal to the RSFSR Supreme Court. This detailed many of the violations of legal procedure also noted by defence counsel Sophia Kalistratova.

↩︎

================================