SEARCHES & INTERROGATIONS

In summer 1980 searches were carried out at the homes of exiles Yevhen Sverstyuk [1] and Oles Serhiyenko [2] in connection with the case of Vasyl Stus (CCE 57.13). Letters were confiscated.

*

On 26 June 1980, the Investigator in the Stus case, KGB Major A.V. Selyuk, interrogated the wife of Yury Badzio (trial, CCE 55.1-1), Svetlana Kyrychenko (CCE 54.11 & CCE 55.1-1). The official reason was that copies of Badzio’s (or Stus’s?) letters from the camps and from exile in Kyrychenko’s handwriting had been confiscated in a search of Stus’s home.

On 4 August, a search linked to the Stus case was conducted at Raisa Rudenko‘s home. A typewriter, a notebook and poetry written in the camps by her husband Mykola Rudenko (1920-2004), which had evaded censorship, were all confiscated.

On 7 August 1980, KGB Investigator N.P. Tsimokh (CCE 45.6 & CCE 53.17) interrogated Raisa Rudenko in connection with Stus’s case. She testified that she had seen Stus once, at a New Year’s celebration and she had liked him very much. He was a brilliant poet, she said, and he had not conducted any “anti-Soviet” or “slanderous” conversations while she was there.

*

On 17 August 1980, Investigator Katalikov of the Moscow KGB (CCE 54.1-2) interrogated Moscow resident Nina P. Lisovskaya (CCE 54.1-1) in connection with the Stus case.

One question he asked: “Did you ask Stus to send you his 19 November 1979 statement to the USSR Procurator’s Office about N.A. Gorbal [Mykola Horbal; trial, CCE 56.15]?” Lisovskaya replied in the negative.

*

TRIAL

From 29 September to 2 October 1980 the Kiev City Court, presided over by Judge P.I. Feshchenko, heard the case of Vasyl Semyonovich STUS (b. 1938), a member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group.

Stus was charged under Article 62, pt. 2 (UkSSR Criminal Code = Article 70, RSFSR Code).

The prosecutor was Procurator Arzhanov.

Despite Stus’s protests and objections, the court appointed lawyer Victor V. Medvedchuk (CCE 55.1 item 3) as his defence counsel, and Medvedchuk appeared for him at the trial [3].

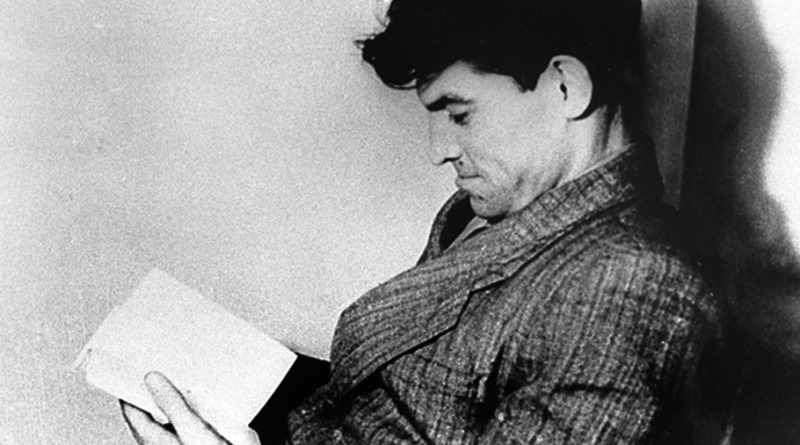

Vasyl Stus (1938-1985)

*

Stus was arrested on 17 May 1980 (CCE 57.13).

During the pre-trial investigation, Stus did not give any evidence. He was incriminated with:

- letters he wrote to Sakharov, Lukyanenko, Grigorenko and to friends in Kiev;

- a statement he made to the USSR Procurator’s Office concerning Mykola Horbal; and with

- poetry and “verbal agitation”.

*

On Thursday, 25 September 1980, Stus’s wife Valentyna Popeliukh telephoned Selyuk, the KGB Investigator: he told her nothing about her husband’s trial.

Late on the evening of 30 September Mykhailyna Kotsyubinskaya [4], Svetlana Kyrychenko and Yevhen Sverstyuk’s wife V. Andrievskaya received summonses to appear next day as witnesses at the trial (1 October 1980).

Only from them did Popelyukh learn that her husband’s trial was already in progress. Yet even on 1 October 1980 she was not admitted to the courtroom.

*

KOTSYUBINSKAYA’S TESTIMONY

Speaking at the trial, Kotsyubinskaya called Stus a man with “a conscience laid bare”, who was “incapable of ignoring the slightest injustice”.

“One rarely meets such people,” she commented: “I’m glad fate brought Stus and me together. I have to thank him for what I have in my life”.

“What could she say”, asked the judge, “about Stus’s statement to the Procurator’s Office concerning Horbal?” (Stus had demanded that a case be instituted against the organisers of the cynical provocation.) This statement, Kotsyubinskaya replied, strikingly confirmed her description of Stus’s character. She, too, had been “convinced of Horbal’s innocence“. Yet she had just grieved over the injustice comitted: Stus’s reaction was immediate and sharp.

The judge requested her evaluation of a 1977 letter Stus had written to Kiev from his place of exile. Kotsyubinskaya refused to comply.

In the letter Stus expressed his wish to join the Ukrainian Helsinki Group.

Do not to fear a tank, he urged people, though it might mercilessly crush every living thing in its path; and he described the line of conduct he would adopt at his forthcoming trial. He would demand, he said, that representatives of the World Congress of Free Ukrainians be present: failing which he would not take part in the trial but simply dot the ‘i’s in a final speech. He would speak as a Son of his People, a Nation which lived in the terrible conditions of a spiritual ghetto.

Kotsyubinskaya refused to comply with the judge’s request, because she was looking not at the original letter, but at a copy: the case file contains only a copy of the letter in Kyrychenko’s hand-writing.

Answering a request by defence counsel Victor Medvedchuk to describe Stus’s political views, Kotsyubinskaya noted the profound humanitarianism and democratism of his views; superficial nationalism was totally alien to him.

If one understood nationalism, however, to mean that “one cannot love humanity without first loving one’s own mother,” then that was true of Stus. He was painfully aware of all the evils of the nation’s life and spoke out against them plainly and sharply.

Stus: Does the witness know that the [1948] Declaration of Human Rights includes the right to hold one’s own views?

Kotsyubinskaya: Yes.

Stus: What about the inviolability of private correspondence?

Kotsyubinskaya: Yes.

Stus: Does the witness know that Christina Bremer is a member of Amnesty International? (Stus was charged with being in correspondence with a nationalist from West Germany.) Could she be a nationalist?

Kotsyubinskaya: As for nationalism — that’s absurd. I understand now why the investigator at the pre-trial investigation did not want to write down the fact that Christina Bremer is a member of the German Socialist Party [SPD = Social Democratic Party].

Stus: Does the witness know that during the pre-trial investigation, on 8 August 1980, I was subjected to physical torture? He did it (Stus pointed at the Deputy Head of the KGB Investigations Remand Centre, who was standing by the door).

Kotsyubinskaya: I did not know that. But if Stus says so, then it’s true.

*

Kotsyubinskaya then described the difficult conditions in which Stus had lived in exile. He was made to live in a hostel, surrounded by drunkards.

The Judge interrupted her and said that these people were present in the courtroom.

Several people from the Matrosovo settlement, Magadan Region (Soviet Far East), where Stus had served his term of exile, had been summoned to the trial to testify to his “verbal agitation”: she must not slander the working class, the judge said.

Afterwards one of the Magadan witnesses was asked whether it was true that Stus’s neighbour, while drunk, had urinated in his teapot. He had not been present when it happened, the witness replied, but there was in fact urine in the teapot. After the questioning was over, Kotsyubinskaya was made to leave the courtroom.

*

KYRYCHENKO’S TESTIMONY

At the beginning of her cross-examination Svetlana Kyrychenko asked the judge:

“I request the court to ask Stus whether he considers this trial legal.”

Stus: I do not.

Kyrychenko: In that case, I refuse to take part in the trial.

*

The procurator demanded that charges be brought against Kyrychenko for refusing to give evidence, and the judge made similar threats.

Kyrychenko responded: “I will testify at a trial where Vasyl Stus is the prosecutor and not sitting in the dock,” and she left the courtroom.

Andrievskaya was also asked about Stus’s letter from exile (see above).

She had read only the part of the letter addressed directly to her, she replied.

*

The following residents of Matrosovo were questioned as witnesses of Stus’s “verbal agitation”:

- the director of the mine where Stus worked;

- Sharikov, head of the mine’s personnel office;

- several workers who lived in the same hostel;

- a nurse from the hospital where Stus was a patient; and

- some salesgirls.

*

CLOSING SPEECHES, VERDICT AND SENTENCE

The procurator’s speech lasted over two hours.

At first, he listed the achievements of Soviet Ukraine, which Stus had blackened. Then he spoke of the crimes of Bandera’s supporters and of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) [5].

Finally, he listed Stus’s “crimes”: the letter from exile; the statement on Horbal’s case; the letters to correspondents in West Germany — Christina Bremer, A. Horbatsch and H. Horbatsch [6]; letters to Andrei Sakharov, Levko Lukyanenko and Petro Grigorenko (the case file contained xerox copies of these letters); and the main crime, his “verbal agitation” while in exile.

*

In his speech, the court-appointed defence lawyer Victor Medvedchuk said that all Stus’s crimes warranted punishment.

He asked the court to take into consideration that Stus had fulfilled his norm, while working at enterprises in Kiev in 1978-1980. In addition, Stus had undergone a serious stomach operation. After Medvedchuk’s speech the court hearing was cut short.

*

On 2 October 1980, the hearing began with the reading of the verdict. Stus was thus deprived of his Last Words in court to which he was entitled by law.

At this session, in addition to the “special public”, Stus’s wife Valentyna Popeliukh and her sister Margarita Dovgan were admitted.

0n the morning of 2 October, Svetlana Kyrychenko was summoned to a police station in connection with “parasitism” and detained until the trial was over: she had not been working for 3½ months, though it is only after 4 months’ inactivity that it becomes permissible to prosecute.

The court gave Stus the maximum sentence: 10 years’ imprisonment in strict-regime camps and five in exile. In addition, the judge imposed court costs of 2,300 roubles on Stus, mostly for the transportation from the Far East of the Magadan witnesses.

*

Judge Feshchenko mumbled and read out the verdict so quickly that neither dates nor names of witnesses could be heard distinctly. After he finished reading, he said without a pause: “The trial is over.” The ‘special public’ headed for the doors.

“You murderers!”cried Stus, “You didn’t even let me make a final speech!”

Then he quoted Lermontov’s “Death of a Poet” (1837):

‘And all your black blood will never wash away / The righteous blood of the poet!’

Stus looked very ill; his face was deathly pale. During a visit after the trial from his wife Valentyna he said he would never survive such a sentence.

*

In Defence of the Poet Vasyl Stus

On 19 October 1980, Andrei Sakharov circulated the following appeal:

“1980 has been marked in our country by many unjust sentences and by the persecution of human rights activists. Even against this tragic background, however, the sentence passed on Ukrainian poet Vasyl Stus is distinguished by its inhumanity.

“The judicial apparatus has acted in accordance with its inhuman laws and subjected him to another 15 years of suffering. A man’s life has been irretrievably broken in reprisal for his elementary decency and non-conformism, for loyalty to his convictions and his own personality.

“Stus’s conviction is a disgrace to the Soviet system of coercion.

“I appeal to Vasyl Stus’s colleagues, to the writers and poets of the entire world, to his academic colleagues, to Amnesty International, to everyone who values human dignity and justice: speak out in Stus’s defence!

“I appeal in particular to the participants of the [CSCE] conference in Madrid … Stus’s sentence must be repealed, as must the sentences of all those involved in the non-violent rights movement to defend the rule of law.”

=================================================

NOTES

As extensive arrests and trials (CCE 58, November 1980) of rights activists and dissidents, such as Vasyl Stus, took place in Russia, Ukraine and other parts of the USSR, a conference prepared to assemble in Madrid.

It was due to discuss various issues relating to the 1975 Helsinki Agreements and involved the 35 co-signatories of the Final Act from North America, Eastern and Western Europe. The conference opened in Spain on 11 November 1980 and would continue to meet intermittently for almost three years.

The gathering had been summoned by the Conference for Security & Cooperation in Europe (CSCE), a body which later became the Organisation for Security & Cooperation in Europe or OSCE.

*

- On Yevhen Sverstyuk (b. 1928), see Perm Camp 36, 1979 (CCE 52.9-2) and Statements (CCE 52.9-3); in Exile, CCE 55.4, CCE 56.22.

↩︎ - On Oles F. Serhiyenko (1932-2016, Alexander Sergienko), see CCE 52.5-2; CCE 54.14 [4], CCE 55.4.

↩︎ - Today Victor Medvedchuk is a vocal and active politician in Ukraine.

See the 20 October 2020 report, published by KHPG on its website Human Rights for Ukraine, “Ukrainian court bans book about the Stus trial that gave Medvedchuk more than he bargained for”.

↩︎ - On Mykhailyna Kotsyubynska (b. 1931), see CCE 45.7, CCE 46.14 [2], CCE 48.3, CCE 49.3.

↩︎ - Stepan Bandera was a leader of the OUN, which fought an armed struggle against the Soviet regime in the years 1944-1953.

↩︎ - The prosecutor, evidently, was actually referring to only one person, Anna-Halya Horbatsch.

↩︎

==================================