On 8 and 9 October the Moscow City Court, presided over by V. V. Bogdanov, heard the case of Yury Leonidovich Grimm (b. 1938 [1]).

The prosecutor was Procurator T. P. Prazdnikova, who also prosecuted Sokirko (and Vyacheslav Bakhmin).

*

THE CASE OF “POISKI”

- 7-1. The case of “Poiski”, introduction,

- 7-2. Victor Sokirko on trial,

- 8-1. Valery Abramkin on trial,

- 8-2. Abramkin’s prison letters,

- 9-0. Yury Grimm on trial.

*

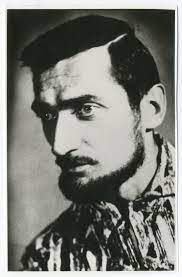

Yury Grimm, 1935-2011

Grimm’s relatives had asked the lawyer Shveisky to act in Grimm’s defence, but he went on holiday just before the trial. The court appointed the lawyer R. M. Beizerov to defend Grimm. Grimm refused the appointed defence counsel, but the court did not accept his refusal and did not release the lawyer from participating in the case.

The trial took place, again, in the same Lyublino district people’s court in Moscow (’The Trial of Tatyana Velikanova’ CCE 58.1). Of Grimm’s friends and relatives, only his wife, son and sister were admitted to the courtroom. Those who were not admitted waited outside. The police and vigilantes behaved correctly (apart from their systematic checking of documents).

*

In one of his petitions Grimm said the following: he was charged with editing Poiski Nos. 4-7, i.e. the issues in which he was listed as one of the editors. However, on the one hand he had in fact actively participated in the publishing of Nos. 1-2 and 3, before becoming a member of the editorial board; and on the other, he had, with the assent of the editors, had no part whatever in the publication of Nos. 6 and 7. Grimm’s explanation for this was that he was continually and closely shadowed and this prevented him from doing anything for Poiski. For this reason, he requested the court to amend the charges.

His petitions not having been fulfilled, Grimm refused to take part in the trial while reserving the right to make a final speech.

*

The witnesses O. Kurgansky, M. Yakovlev, V. Sorokin and N. Kasatkin were questioned. The court also summoned Yekaterina Gaidamachuk and Victor Tomachinsky as witnesses, but they did not turn up.

Kasatkin’s evidence was the same as at Abramkin’s trial, except that this time he categorically asserted that it was Abramkin who had given him the journal. He had met the accused at Egides’s home (’Egides is the ringleader of the gang’), then they had gone to Grimm’s home: both Grimm and his wife assert that this did not happen. Grimm had asked Kasatkin to help duplicate the journal.

Yakovlev’s evidence was the same as at Abramkin’s trial. The Procurator reminded him that a criminal case had already been started against Sorokin — the same could happen to him. Yakovlev, however, did not change his evidence. (The case against Sorokin was not started until 4 November; that against Yakovlev, on 4 December.)

Kurgansky, from whom the prosecution tried to obtain confirmation of the evidence he had given in the pre-trial investigation, was adamant: the evidence had been given under duress (‘The Trial of Abramkin’ CCE 58.8-1). In his evidence he reported on the latest trials and arrests.

*

Sorokin repeated the evidence he had given at previous trials; he recounted the gross violations of the law committed by the Procurator (Procurator: ‘You cite the law too often!’), described the journal Poiski, described Yury Grimm, and then, citing violations of the Code of Criminal Procedure (in both this and previous trials) and of the Constitution, Sorokin refused to answer any further questions on the case.

Procurator: Then why did you spend a whole hour driving us round the bend, if you don’t want to give evidence?

Sorokin: I availed myself of the right to say everything I know concerning the present case.

The Procurator’s recommendation; three years’ strict-regime camp (strict-regime because Grimm had been convicted previously, see below). The defence lawyer’s recommendation: Grimm should be acquitted, as the charges had not been proved.

*

In his final speech Grimm dwelt in detail on the following aspects of the case:

[1] The separation of his own case from the Poiski case as a whole. In Grimm’s opinion, this had been done in order to lend weight to the charges against him personally. (Each of the accused was being charged individually with the activities of six or seven people, which were well beyond the strength of one person alone.)

To this end the entire second volume of the case was filled with information derived by transcribing broadcasts of foreign radio-stations. The investigation was in such a hurry to increase the volume of the case that the indictment contained passages such as the following: ‘In December 1979 Grimm circulated the seventh issue of the journal. The fact that it was circulated is proved by reference to a Radio Liberty broadcast of 28 September 1979’.

[2] Grimm stressed once again that he had not had any part in Nos. 6 and 7 of the journal even though his name was on the title page, and that, on the other hand, he had collaborated in issues 1-2 and 3, even though not officially one of the editors.

‘As a member of the editorial board of the journal, and in particular as one of the listed editors of Nos. 6 and 7, I am by no means evading my responsibility for the material in these issues,’ he said. ‘However, I state once again that I did not collaborate in the 6th and 7th issues.’

[3] Grimm dwelt particularly on the fate of his article ‘Will This Happen Again?’ He stated that he had written this article not for publication in Poiski, but simply for samizdat.

He had been amazed to learn during the investigation that his article had been published in the seventh issue of Poiski. He did not see anything slanderous in the article: it was an account of his personal impressions of a 15-day jail sentence. Grimm further reminded the court of his work record and drew its attention to the substance of his first ‘case’ in 1964 (see below).

Grimm concluded that he had foreseen the outcome of the case and knew the sentence in advance, and it was for this very reason that he had chosen his stance of non-participation in the trial. It had been a pleasant surprise for him that the appointed defence counsel. Beizerov, had been able to fulfil his task with the necessary attention and had, despite the lack of assistance from his client, carried out the defence intelligently and lucidly.

The court imposed the following sentence; three years of strict-regime camps.

*

On 13 November the Moscow Helsinki Group adopted Document No. 147, ‘The Trial of Yury Grimm’:

“… One’s attention is arrested by the fact that Grimm was charged with the compilation, production, duplication and circulation of the journal Poiski … i.e. the same acts for which other members of the Poiski editorial board, Abramkin and Sokirko, were convicted.

“The investigation of all three was carried out under one case. Just before the end of the pre-trial investigation, the cases of Abramkin, Grimm and Sokirko, in violation of article 26 of the RSFSR Code of Criminal Procedure, were separated into three individual cases. Thus, Grimm and Abramkin were deprived of the opportunity of a joint defence against a common indictment of both of them.“

*

Grimm is a photographer by profession. In January 1964 he was arrested and sentenced under article 70 of the RSFSR Criminal Code circulating some caricatures of Khrushchev (CCE 11.2). After the fall of Khrushchev the case was re-examined and in April 1965 his sentence was commuted to three years.

After his release he worked as a building worker. In 1975 Yury Grimm and his family applied to emigrate to Israel, but they were refused permission.

Grimm joined the editorial board of the journal Poiski in 1978.

=======================================

NOTE

- According to another source, Grimm was born on 16 April 1935.

↩︎

========================