As reported in CCE 52.9-2, Mustafa Dzhemilev was arrested on 8 February and charged with ’malicious violation of the rules of administrative surveillance’ (Article 199-3, Uzbek SSR Criminal Code).

On 18 February, at the same time as declaring a hunger-strike, Mustafa Dzhemilev wrote a statement to the President of the people’s court of the October district of Tashkent, a copy of which he sent to the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet. In this statement he demonstrated that the case against him was brought illegally and demanded that he be

‘released from custody, that the guilty parties be prosecuted, that my right to live in the Crimea be granted, or that the opportunity be given me to leave the USSR.’

Dzhemilev asserted that his case had been inspired by the organs of State Security, to which in particular the following document, included in the statement, bore witness:

To the Head of the October district OVD, Tashkent, Lt-Col R. Yu. Yuldashev

Report

I report that on 29 December 1978 a statement was received from Mustafa Dzhemilev, a man under surveillance, who asked in a threatening tone for permission to leave for the Crimea, and at the same time demanded to know by what right we had placed him under administrative surveillance. Comrade Salomatov and I informed KGB official Grabovsky of this by telephone. At 6 pm Grabovsky himself arrived and asked to be given Dzhemilev’s statement in return for a signed receipt. He promised to reply to the statement in our name (italics mine, M.D.).

On the morning of 30 December Dzhemilev was detained by KGB officials at the airport as he was taking off for the Crimea. I again telephoned Comrade Grabovsky and asked how to proceed, and Comrade Grabovsky told me to proceed according to the law. We prepared the evidence and Dzhemilev was fined 30 roubles by the people’s court for violation of administrative surveillance, and then released.

(A. Akhmedov) Deputy Head of October district OVD

30 December 1978

The prison administration did not send the statement to either of the addresses, and Dzhemilev was not informed of this. For the first two weeks he was kept in an ordinary cell, then he was transferred to a solitary confinement cell in the cellar. He was force-fed every other day.

On 26 February Judge E. A. Petrov informed Mustafa’s brother Asan Dzhemilev that the trial was fixed for 1 March. Asan made a statement requesting that the date of the trial be postponed to 5 March, since the Moscow lawyer V. Ya. Shveisky, who had agreed to defend Mustafa Dzhemilev, was engaged on another case on the 1st (Shveisky defended Dzhemilev in his trial at Omsk, CCE 40.3). Petrov replied with a categorical refusal.

On 1 March relatives, friends and compatriots of M. Dzhemilev gathered outside the October district people’s court building; A. D. Sakharov, who had come for the trial, was among them. They waited for half a day, but the trial did not take place. Judge Petrov stated that the accused had not been brought from prison ‘For an unknown reason’ (the next day the lack of an escort was given as the reason), and therefore the trial would be postponed; it would not take place earlier than 11 March, as until then he, Petrov, would be extremely busy.

He gave the same answer to the lawyer who phoned to say that he was prepared to come on 6-7 March, if the trial could take place then. As Shveisky was again occupied on 11 March, an agreement was concluded in Moscow on 4 March with the lawyer E. S. Shalman (CCE 50.1, CCE 50.7), and Petrov was informed of this by telegram. Those who gathered at the court on these days were subject to intensive surveillance.

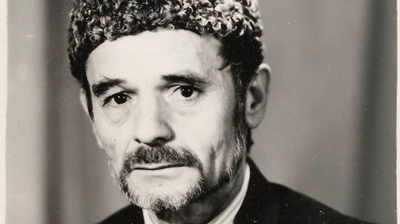

Mustafa Dzhemilev (b. 1943)

*

TRIAL

During the evening of 5 March, prison officials confiscated from M. Dzhemilev all the notes and materials in his possession relating to the case.

The trial took place on 6 March. Neither the lawyer, Shalman, nor the relatives of the accused were informed that the trial was beginning. Dzhemilev was taken to Judge Petrov’s office, where two assessors, a secretary, some sort of lawyer and three policemen were waiting. Petrov announced that the court hearing had begun.

Dzhemilev refused the lawyer provided for him and submitted a number of petitions: that he be allowed to choose a lawyer at his own discretion, that the confiscated notes be returned to him, that they call supplementary witnesses (his relatives, who could confirm that on the evening of 19 January he had been at home, and thus refute one of the charges), and finally, that the hearing be open and take place in a courtroom, not an office. All the petitions were turned down; for this reason, Dzhemilev refused to take part in the trial. However, he presented a written statement where he again testified to the groundlessness of the charge. Dzhemilev was taken from the room and locked up in a cell attached to the court. After about an hour he was informed that the case would be heard in his absence (The Code of Criminal Procedure expressly forbids this).

The Judge telephoned Mustafa’s brother Anafi Dzhemilev at work, and told him to find Asan Dzhemilev for a court appearance. ’It so happened’ that Asan was away on business. In this manner the beginning of the trial became known. Several of Mustafa’s relatives and friends managed to push their way in to where the case was being heard.

The Judge announced that the accused had refused to take part in the trial, and that therefore the hearing would take place in his absence. Those relatives and friends who were present left the premises in protest. Only policemen and KGB officials stayed. Four hours later the court came to the cell where Dzhemilev was waiting and the Judge pronounced sentence.

In the judgment it was said that Dzhemilev, ‘in violation of the administrative surveillance placed on him …led an antisocial life, maliciously declined to obtain employment or register an address’, and did not respond to prophylactic talks and warnings regarding employment, in connection with which surveillances had been twice extended. The judgment referred to the evidence of four witnesses; policemen Sidikaliev, Atashkulov (CCE 49.12), Salomatov and Akhunov. (The witnesses who had signed the report that Dzhemilev was not at home on 19 January were not questioned in court.)

In conclusion it states:

‘Dzhemilev’s allegations about the groundlessness of the charges brought against him are fabrications by which he hopes to escape criminal responsibility. The allegations are disproved by the evidence of the case.

‘In determining a punishment for Dzhemilev, the court has taken into account his character and the fact that he has a dependent daughter who is a minor, and the court also takes notice of the humane character of Soviet law in relation to citizens.’

The court sentenced him to 1 (one) year and 6 months’ deprivation of liberty.

However, applying to Dzhemilev Articles 24 and 42 of the Uzbek Criminal Code, a lighter punishment is fixed for him, penalizing Dzhemilev with exile for a period of 4 (four) years.

*

They dragged Mustafa into a Black Maria — it was the seventeenth day of his hunger-strike. On 8 March Dzhemilev sent a statement to the court requesting to be shown a record of the trial. He did not receive an answer.

On 11 March relatives eventually managed to arrange the meeting which was due after the trial. Mustafa was very weak and complained of pains in the heart. He had not yet received a copy of the judgment (which by law should be handed to the convicted person not later than 72 hours after its pronouncement). The meeting was terminated after half an hour, as Mustafa and his relatives, out of habit, had spoken a few words in Tatar and they had been ordered to speak only Russian. That day Mustafa ended his hunger-strike. On 10 March Mustafa’s sister Dilyara Seitveliyeva, who was then still living in the Crimea (this issue CCE 53.22-1), declared a three-day hunger-strike in protest.

*

APPEAL

On 18 March M. Dzhemilev submitted an appeal to Tashkent City Court, to which he attached his statement of 18 February. On 19 March the appeal was forwarded by the prison administration to the October district people’s court, but with no attachment. Thus the statement never reached the court. On 20 March Judge Petrov transmitted Dzhemilev’s case to the City Court.

On 21 March Judge Petrov informed lawyer E. S. Shalman that the hearing was fixed for the 22nd. Shalman immediately sent a telegram saying that since he had only been informed half a day before the trial was due to begin, he could not be there at the designated time. Therefore, he requested that the hearing be postponed until any day after 1 April, and that he be informed of the new date in good time.

On the same day, 21 March, Asan Dzhemilev tried to find out from the district court where Mustafa’s case file was. The district court had sent it to the City Court, but here he was informed that they had not yet received the case, and that therefore the date for the trial was not known.

All the same, by 9 am on 22 March more than 50 of Mustafa’s friends and relatives had gathered outside the City Court building. At 10 am the list of that day’s hearings appeared on the notice-board. The hearing of the Dzhemilev case was fixed for 14.30, with B. B. Oks presiding. Relatives asked Oks to accept their statement asking for the hearing to be transferred to I April. Oks refused and informed them that the petition could be accepted only at the actual trial. They could not find out, either from Oks or from the Court Secretary, in which of the rooms the hearing would take place. Eventually, at 14.30, Oks informed the relatives that ‘the materials of the court of first instance relating to the case of the convicted Mustafa Dzhemilev had been reviewed at 10 am’ and that the sentence remained the same.

*

EXILE IN YAKUTIA

At the beginning of April relatives were informed that Mustafa was in transit to his place of exile in Ust-Maisky district, Yakut ASSR (southern Yakutia). However, on 31 May Dzhemilev was taken to Kolyma (Soviet Far East), to Zyryanka Settlement, Verkhne-Kolymsky district, Yakut ASSR. In view of the ‘severe housing shortage’ in the settlement he was put at first in the foyer of a local hotel. Soon afterwards Dzhemilev found employment and a place in a hostel.

On 5 June Dzhemilev sent a statement to the USSR Procurator-General, which was copied to Major V. F. Masalov, head of the district office of internal affairs (OVD). He asked (and this same petition had been included in his appeal) for his four years of exile to be changed back to one-and-a-half years’ deprivation of freedom. One of the reasons for such a request was that his chances of finding his sick 82-year-old father still alive at the end of his term would be greatly increased. As a last resort, Dzhemilev asked to be transferred to another district where the housing problem was not so severe, and he could live with someone close to him.

*

On 4 May the newspaper Evening Tashkent published an article entitled ‘Profession: Sponger’ by Yu. Kruzhilin on the trial of Mustafa Dzhemilev. Kruzhilin discusses the ‘impressions’ of Mustafa made on him after attending the trial and chatting to the district Procurator, the district OVD Head of the district OVD Social Prophylaxis Service, witnesses and relatives.

Mustafa was expelled from college for a disciplinary offence, was soon afterwards convicted for evading call-up for military service, then convicted a second time for not appearing for military training. In camp he refused to work, ‘behaved provocatively and committed violations of discipline. This was his third crime, and it brought a new trial’. Regaining his freedom in 1977 after four convictions and eight years of camp ‘in total’, Dzhemilev was totally indifferent to the numerous warnings he received to register his address and find employment. And, after all,

‘in accordance with the law, housing is allocated to such people [sic! Chronicle] and they are placed under administrative surveillance. The task is to help them on to the right tracks. And so, in the hope that Mustafa would come to his senses, the district Procuracy extended the surveillance for another six months.

‘And then one more time, but nothing had an effect on Mustafa, who unceasingly continued to violate the rules of administrative surveillance, did not work and lived without registering an address.’

Dzhemilev had submitted a statement to the court, in which he writes that

‘they are not dealing with him … legally! The Judges carefully considered even these laughable arguments. They painstakingly tested the soundness of every word spoken by the witnesses, every letter in the documents of the case. And they fixed ‘a punishment lower than the lowest limit’.’

But Mustafa was not content with this and sent in ‘an appeal: he said that this exceptionally light sentence was too hard for him’. Kruzhilin then criticizes the court:

‘He was again not brought to justice for parasitism and breaking the residence regulations. The Judges did not concern themselves with the source of Mustafa Dzhemilev’s money, which he obviously came by dishonestly.’

*

A letter from Asan Dzhemilev to the editor of the newspaper (a reply to this article) was circulated in samizdat (10 pages).

A. Dzhemilev discusses his brother’s participation in the Crimean Tatar movement and presents the real reasons for his four convictions. For example, Kruzhilin was silent on the subject of Mustafa’s conviction to three years’ camp for ‘the circulation of deliberate fabrications …’ in 1969, and he called the trial in 1976 on the same charge (CCE 40.3) a trial for violating camp discipline. Asan Dzhemilev discusses in detail the course of events regarding the most recent conviction and the fact that the court took no note of the evidence of Mustafa’s innocence. Kruzhilin lied in saying that he had talked to relatives.

=====================================