[See CCE 52.4; CCE 53.16; CCE 54.3; CCE 55.2-2 & CCE 56.5]

On 27 May 1980, the day of Tatyana Osipova’s arrest (CCE 57.2), Investigator Sazonov of the Moscow City Procurator’s Office conducted a search linked to the case of the journal Poiski at the home of Yu. Denisov, who works as a waiter at the Budapest Restaurant. The search warrant was issued by Senior Investigator Yu. A. Burtsev.

The search record contains 77 points. The confiscated items include a large quantity of samizdat and foreign publications, poems, articles, newspapers, several issues of the new samizdat journal The Duel – on 10 April it had already been confiscated in a search of Osipova’s home, CCE 56.3 – and a statement by the editors of the journal Poiski (dated 20 May 1980). A typewriter, recording tapes and cassettes were also taken. One of the tapes (containing lectures on the subject of ‘Russian Dissent’) was handed over by Denisov of his own free will, in the hope that the remaining tapes of ‘neutral content’ would be left in his possession.

In his comments written on to the record Denisov stated that he considered the confiscation of the typewriter belonging to his wife — a professional typist — unlawful; he also protested against the confiscation of his materials and tapes, which bore no relation to “materials defaming the Soviet system”.

On the previous evening a search was made at the flat of Yu. Denisov’s mother-in-law linked to the same case. Approximately the same amount and kind of material was confiscated.

*

On 27 May 1980, Investigator Titov of the Moscow City Procurator’s Office conducted a search of Maria PETRENKO’s home linked to Case No. 50611/14- 79.

Private correspondence (many letters were from abroad), materials on Victor Nekipelov and other human-rights activists, two Gospels published in Finland, and a manuscript by her son-in-law Sergei Nekipelov about service in the army were confiscated. Several letters Petrenko had written to official institutions were also taken. The searchers refused to show their documents and did not let her copy out the search warrant. M. Petrenko’s daughter Anastasia Podyapolskaya and her husband Sergei Nekipelov, were detained in the house for the duration of the search, which lasted 12 hours. They were given no certificate to account for their absence from work.

On 4 June, at the Procurator’s Office, Petrenko was issued a “warning in accordance with the Decree”. The materials she was ‘charged’ with possessing, included the rough draft of a letter in defence of Victor Nekipelov and photocopies of several rough drafts confiscated in the search of Osipova and Kovalyov’s home on 10 April (CCE 56.3). These concerned a ‘chat’ with her. Petrenko would be prosecuted for slander, she was told, and for refusing to give evidence.

*

On 24 June 1980, Sergei NEKIPELOV received a telephone message summoning him from work to the City Procurator’s Office, where he had a chat with G.V. Ponomaryov.

Ponomaryov asked Nekipelov how his letter to Strauss (January 1980), in which he wrote that his family was being subjected to persecution, had reached the West. And what did he mean by ‘persecution’? Sergei Nekipelov replied that the KGB had files on four out of the five members of his family, and criminal cases had been started against some of them.

Ponomaryov also asked what he meant by ‘that monster’ in his letter, which had been broadcast by Radio Liberty. “You are sufficiently intelligent people to understand that without any explanation from me,” said Nekipelov. This offended his interlocutors.

Ponomaryov left the room, whereupon two ‘officers’ who did not give their names, but who had been present during the chat, attempted to persuade Nekipelov that he was in fact guilty of nothing, but had merely fallen under the bad influence of others, who were presenting him as the son of a ‘great martyr’ (i.e., Victor Nekipelov). Then his interlocutors returned to the question of how his letters had ended up abroad. Nekipelov refused to answer. Questions followed about documents which had been confiscated on 27 May 1980 during the search of Maria Petrenko’s home. A forensic test showed that Sergei Nekipelov was the author of many of these documents.

He had fallen under the influence of Petrenko, Nekipelov was told, a woman who carried out her activities illegally – as opposed to his father Victor Nekipelov, who carried out his anti-Soviet activities legally.

Sergei Nekipelov said he would discuss all the confiscated documents bearing his signature in more official surroundings. The accusations against Maria Petrenko, he said, were without substance. When a case was started against Sergei Nekipelov — they hinted that he would be charged under Article 190-1, RSFSR Criminal Code — they explained, there would be an official interrogation. Concerning Petrenko, they said that many young people gathered in her flat: they already had statements from parents about what went on there. From what they said next it became clear that the Petrenko flat was bugged, and all members of the family were under surveillance. They then asked Nekipelov what plans he had for the future. He refused to discuss personal matters. In conclusion he was issued an oral ‘warning’ that criminal proceedings were being instituted against him.

*

On 3 July 1980, in the town of Troitsky (Moscow Region), Investigator Yu. A. Burtsev conducted a search at the home of Valery Godnev, a computer programmer at the Nuclear Research Institute, USSR Academy of Sciences.

Godnev voluntarily handed over typed texts, photocopies and books published abroad. The confiscated items included issues of the journal Kontinent and works by Solzhenitsyn, Berdyaev and Nabokov. After looking through the books Godnev handed over, Burtsev asked, “And where is Poiski?” Poiski No. 7 was taken from Godnev’s briefcase. The search record contains 33 points in all. One referred to a typewriter: Godnev said he had not typed anything on it. Burtsev made a note of this on the record. They could not find Godnev’s address book in the search. The searchers grabbed Godnev and took him to his place of work; there they took away his address book and several copies of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights [1948] which had not been fully typed. They did not leave a copy of the record of items confiscated at work. Burtsev then handed Godnev a summons to an interrogation on 4 July.

At the interrogation Burtsev asked Godnev about his acquaintance with several persons, including members of the Poiski editorial board. Godnev said that he did not know any of the board members. He did not deny knowing Sergei Belanovsky (CCE 45.18 [8], CCE 54.2-1 & CCE 55.10-1), whose telephone number was in his address book. Godnev refused on ethical grounds to tell them where he had obtained the confiscated material.

During the interrogation, Burtsev showed Godnev the copyright sign (the letter c in a circle) and told him that a ‘first edition’ copy of Poiski had been confiscated from him. He said that the size of the print-run (20 copies) quoted by the West German radio-station Deutsche Welle was heavily exaggerated. Burtsev also stated that an expert examination had shown several issues of Poiski to contain ‘slanderous fabrications’. In the second half of July Godnev signed a record of a “warning in accordance with the Decree”.

*

On 4 July 1980, Investigator Burtsev interrogated Sergei BELANOVSKY.

Belanovsky did not refuse to answer questions, but requested permission to register a complaint beforehand in the record. He wished to complain about Burtsev’s actions during the search of 13 September 1979 (CCE 54.2-1). Burtsev did not agree to this. He also refused to show Belanovsky an inventory of the materials sealed in a bag during the search without having been sorted out.

Several times during the interrogation Burtsev threatened to register a “refusal to give evidence”. No record of the interrogation was drawn up. (The same happened during an interrogation of Belanovsky at the end of February 1980.) Burtsev rebuked Belanovsky for sending postcards without telling him to Abramkin and Sokirko in prison. Belanovsky did this, Burtsev stated, with the intention of supporting the criminals: in any case, the postcards had not been delivered.

At the end of July 1980, while Belanovsky was away on an Olympic business trip, a notice arrived at his Moscow address summoning him to another interrogation.

*

At the end of July Burtsev twice interrogated Valery ABRAMKIN’s mother. The questions chiefly concerned Abramkin’s wife Yelena Gaidamachuk and Gleb Pavlovsky (CCE 52.17 [8], CCE 55.2-2 & CCE 56.5). Abramkin’s mother said that she knew nothing about her son’s activities.

In June and July 1980, Abramkin, who is in being held in Butyrka Prison, was denied access to the prison shop and to parcels for “systematically infringing the regulations”.

*

Early in May Vladimir GERSHUNI, a member of the Poiski editorial board, received the following anonymous letter:

“Hey, you lunatic!

“Stop your scurrying around. Just think, you blockhead, what you’re up against!

“We’re not afraid of you anyway; you might have to spend the rest of your days without any teeth. Anyway, it’s high time you were in a loony bin.”

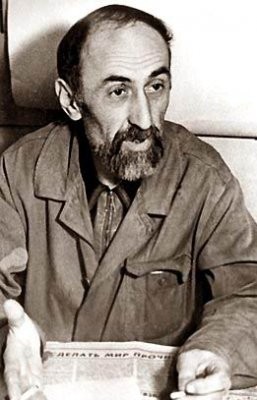

Vladimir Gershuni, 1930-1994

On 26 June 1980, Gershuni was arrested in the street and taken to Police Station No. 131. There he chatted with the doctor who signed his last discharge (in 1974) from psychiatric hospital No. 13. Why had he not come to the hospital? she wondered, suggesting that he ought to be hospitalized. Gershuni was then taken to Psychiatric Hospital No. 13.

That night he began to have abdominal pains and to run a high temperature. He did not manage to obtain a medical examination, however, until mid-afternoon on 28 June. He was then urgently transferred to City Hospital No 1: there he was operated on for suppurating appendicitis – peritonitis had already begun. After the operation an orderly from Psychiatric Hospital No. 13 stood guard in the corridor.

Then Gershuni, with his abdomen still bandaged, was transferred to the psychosomatic department of the City Hospital. He was not allowed out for exercise. On 15 July, Gershuni was transferred back to the psychiatric hospital [note 1].

*

In May 1980, Pinkhos A. PODRABINEK (CCE 48.7) was summoned to the town soviet executive committee in Elektrostal (Moscow Region) where he lives. There he was met by the committee Chairman, the Town Procurator, the Secretary of the town Party committee for ideological work, and a senior research officer of ‘the scientific communism faculty’ at some institute.

To begin with, they talked about the hopeless electrical wiring in Podrabinek’s flat. Very soon they turned to the article he and Pyotr Egides had written about “Contemporary Problems of the Democratic Movement in Our Country”. It was published in Poiski No. 5.

*

On 16 July Vsevolod KUVAKIN (CCE 48.18, CCE 53.25-1, CCE 54.22 [12] & CCE 56.25 [11]) was summoned to the Moscow Procurator’s Office and given a “warning in accordance with the Decree” . Kuvakin was told that his article published in Poiski had been found by experts to contain ‘slanderous’ statements.

======================

NOTE

[1] In August 1980, after the Olympic Games were over, Gershuni was released from the hospital.

======================