<< No 33 : 10 December 1974 >>

According to advance information received from the labour camps of Mordovia and Perm, a decision was taken there to designate 30 October 1974 [1] the “Day of the Political Prisoner in the USSR”.

*

Prisoners intended to declare hunger strikes, lasting for one or two days, on 30 October.

Certain demands which the hunger-strikers wanted to put forward then are known to us. They include:

- recognition of political prisoner status;

- separation of political prisoners from criminal convicts and war criminals;

- abolition of forced labour and compulsory norm-fulfilment;

- abolition of restrictions on correspondence, including correspondence with other countries;

- abolition of restrictions on parcels and gifts;

- removal of Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD) authority over the medical staff in places of imprisonment;

- provision of full medical services for prisoners, with allowance for visits by specialist doctors, including doctors from abroad;

- an increase in the number of permitted visits by relatives and permission for visits by friends;

- provision of opportunities for writers, scholars and artists to engage in creative work;

- permission to register marriages; and

- permission for prisoners to talk in their mother-tongue in the camp and during meetings with relatives.

♦

The Chronicle does not yet know what happened in the camps on 30 October 1974 (compare events in 1975: CCE 38.12-1, CCE 39.2-1 & CCE 35.7).

In Moscow, that evening, Western correspondents received information about “Political Prisoner’s Day” at a press conference organized by Andrei Sakharov and the Action Group for the Defence of Human Rights in the USSR (Action Group).

Valentin Turchin, chairman of the Moscow group of Amnesty International (CCE 34.18 item 1), attemded the press conference as an observer.

“The organizers of this press conference regard it as an expression of solidarity with Soviet political prisoners,” said a statement given to the journalists: “We are also counting on widespread support from world public opinion.”

The statement outlined the main difficulties of the life led by political prisoners in the USSR:

- excessively long terms of imprisonment;

- bad and severely insufficient food, which cannot be supplemented from parcels, since these are strictly limited as to weight and number;

- widespread and unsupervised punitive measures;

- oppressive work conditions;

- poor medical services, and so on.

The statement emphasizes that Soviet political prisoners “have been convicted for actions, opinions and intentions which would not be regarded as grounds for prosecution in a democratic country”.

“We do not yet know what happened there today, behind the barbed wire. But we are certain that today, as always, political prisoners will reassert their dignity as human beings and their sense of inner justification.”

Journalists were handed copies of Open Letters by prisoners [2] and other material received from labour camps.

These documents are presented here in brief extracts: see the CCE Archive and CHR for full versions, in Russian and English, respectively.

The majority are dated October and were written specially for Political Prisoner’s Day.

*

[1]

WOMEN IN THE CAMPS

An Open Letter to the Women’s International Democratic Federation [3] asks the Federation to demand the following from the Soviet Government:

- the release of women political prisoners (cf. CCE 34.8 item 4),

- the open publication of the materials of their cases, and

- the opportunity for Federation members to see for themselves the conditions under which women prisoners are held (this issue CCE 33.4, “In the Mordovian Camps”).

The letter was signed by Kronid Lyubarsky, Sergei Babich, Israil Zalmanson, Zoryan Popadyuk, Alexander A. Petrov-Agatov [4], Boris Azernikov and Boris Penson. (For part of the text, see CCE 33.4 this issue.)

*

[2]

CORRESPONDENCE

In an Open Letter to the World Postal Union (WPU) [5], Azernikov, Lyubarsky and Penson speak of systematic “breaches of the obligations which the USSR Ministry of Communications assumed when the Soviet Union joined the WPU.”

They are not referring, the authors stress, to Soviet legislation about restrictions on prisoners’ correspondence and the censorship of their letters: that is outside the competence of the WPU. The letter states:

“Scores, even hundreds of letters … disappear without trace … with no explanation and complaints remaining unanswered.”

Some political prisoners fail to receive 20 to 50 % of all their mail: there have been individual cases of prisoners who are completely deprived of letters over long periods [6].

Letters are frequently delayed for months; telegrams are held up for many days, sometimes for weeks.

Unlike that which “disappears”, correspondence officially withheld by the censors, is usually not returned to the senders, and the latter receive no compensation.

Incidentally, the confiscation of letters in such cases is against Soviet law.

The letter to the World Postal Union continues:

“We ask you to take into account the extreme limitations on our own means of protest.

“We need the help of organizations with authority, directly concerned with the problems we have raised.”

*

[3]

HEALTH CONDITIONS

In an Open Letter Boris P. Azernikov, a dental surgeon, describes the dangerously unhealthy conditions under which prisoners are held in the “strict-regime” labour camps of Mordovia, and the extremely low standard of the medical services in these camps.

*

The prisoners live in a state of “disguised starvation”, writes Azernikov:

“Even the maximum calorie count of the food received is about 2,000 calories less than the amount necessary [this issue CCE 33.2] for the hard labour in which prisoners are engaged. The food contains practically no animal protein or vitamins. Cases of food poisoning are not infrequent.

“The air in the workshops is thick with sawdust powder and abrasive dust, acetone and acid fumes. … This is conducive to the development of silicosis and other lung diseases.”

*

Medical treatment does not begin until an illness has reached a critical stage, and even then it continues only until the symptoms disappear.

Chronic illnesses — gastro-enteric, cardiovascular and eye diseases; rheumatism, mycosis and periodontosis — are not treated at all, although they exist on a massive scale in the camps.

A sick man is permitted exemption from work only if his temperature is above 37.4 degrees Centigrade. Exemption due to illness, without a high temperature, is extremely rare.

The doctor cannot exceed the limit of the so-called ‘exemption norm’ (1.7 % of all prisoners) “even during influenza epidemics.”

*

There are no doctors in some camps; their place is taken by doctors’ assistants or nurses. Specialist doctors visit the camps once or twice a year or even less frequently.

Prisoners who are themselves doctors may not help their sick comrades. They are expressly forbidden to do so.

Camp doctors have only the simplest medicines at their disposal, and some of these are far past their period of validity. Camp chemists lack effective modern drugs, e.g., many antibiotics. But “the sending of drugs into the camp from outside is forbidden”.

*

The dirt road between the camp and the hospital is so bad, and camp vehicles so unsuitable for transporting the sick, that the journey may cost a sick man his life.

Broken limbs and spinal injury have in some cases resulted from these journeys. For heart patients a journey over this road is simply unbearable.

“Often […] people completely healthy in mind when they arrive in the camp […] become mentally ill towards the end of a long term.

“Such sick people receive no treatment whatsoever. Frequently prison cells and punishment cells are used to isolate them. There have been no instances when even the very seriously ill have been released.”

Azernikov asks for help for those suffering inhuman treatment. “This should not, and cannot be delayed”, he concludes, “by transient political considerations.”

*

[4]

SCIENTISTS & SCHOLARS IN THE CAMPS

Kronid Lyubarsky (1934-1996)

In a letter describing the effect of camp routine and conditions on the professional future of prisoners who are scholars and scientists, astrophysicist Kronid Arkadyevich LYUBARSKY has appealed to: the executive council of the World Federation of Scientific Workers, and the executive committee of the Congress for Cultural Freedom [7].

“We are not just deprived, temporarily, of freedom,” writes Lyubarsky. “We are forever deprived of our profession, of the work we love.”

In a labour camp it is strictly forbidden to receive any scientific or scholarly literature, even highly specialised texts, if they were published abroad.

Literature published in the USSR can be obtained from mail-order shops, but only recently published books in little demand are actually available there.

Private individuals are categorically forbidden to send any literature.

Private letters from colleagues — especially those abroad — containing information about science and scholarship, are delayed by the censors for many months, and often withheld altogether.

*

Academics, most no longer young, are subjected to hard physical labour in the camps, to which they are not accustomed; it leaves them neither the strength nor the time for intellectual work.

The impossibility of following developments in their field, exhaustion and systematic malnutrition, Lyubarsky believes, eventually render scientists and scholars serving long terms of imprisonment wholly incapable of continuing to work in their professions.

Lyubarsky calls on the Federation and the Congress, and on scientists and scholars all over the world, to obtain the right of free access to academic literature for Soviet political prisoners, the right to academic contacts.

He calls on scholars and scientists to send scholarly and scientific material to their political-prisoner colleagues.

♦

[5]

EMIGRATION

In an Open Letter, Boris P. Azernikov speaks of the reasons which first made him decide to leave the USSR, thus landing him in a corrective-labour camp.

“Why am I here? Why could I not be elsewhere?

“I realized that I had been robbed. I had been robbed of my history, my forbears, my language … so that I would not even think of resisting the attempts to herd me into a faceless ‘new historic community’, the ‘Soviet Nation’.

This realization has determined the whole subsequent course of my life.

“I did not try to shake the might of the Soviet Union …

“I wanted only to leave it for another country which, whatever it may be like, good or bad, has for me the unquestionable advantage of being the land of my people. However, in the eyes of the Soviet Government – which once [under Lenin] published ‘A Declaration of the Rights of the Peoples of Russia’ – this wish of mine almost automatically made me a criminal; and so here I am, in a labour camp …

“Today, on ‘Political Prisoners’ Day’, remember those who, before they can step on the soil of their Homeland, are still fated to spend long years in Soviet labour camps.

Today, they cry out: ‘Deliver me, o my God, out of the hand of the wicked, out of the hand of the unrighteous and cruel man’ (Psalm 71, verse 4 [8]).

“We shall not forget them! We shall say today with hope and with them: ‘Next year in Jerusalem!’”

♦

[6]

INTERVIEW

Western journalists were also handed copies of an interview to which many Camp 35 (VS-389/35) prisoners in Perm contributed: Ivan Svetlichny, Ihor Kalynets, Ivan Kandyba, Lev Yagman, Semyon (Slava) Gluzman, Zinovy Antonyuk, Arie Khnokh, Josif Meshener, Yevhen Prishlyak, Vladimir Balakhonov and Bagrat Shakhverdyan [9].

The interview deals with the legal position of political prisoners, the harshness of the labour camp regime, the prisoners’ relations with the administration, the many instances in which political prisoners have acted in defence of their rights, etc.

By imposing the strictest isolation, say the prisoners, the authorities are trying to hide the truth about the kind of life led in the camps, the life of men [and women] convicted contrary to the civil freedoms declared in the 1936 Constitution.

The rules of censorship effectively allow any letter to be withheld, encouraging the tyrannous behaviour of the censors. The destruction of such letters rules out any possibility of checking on the reasons for which they were withheld.

Although the declared aim of the authorities [corrective-labour] is to win round prisoners by force of argument, they are powerless and make no attempt to do so: their real aim is to break a prisoner, to force him to renounce his views.

The camp or prison administration tries to achieve this by constant fault-finding and punishment, by illegally subjecting the prisoners to mental and physical suffering — humiliation, hunger, cold, etc. Heavy, at times senseless, labour has become an instrument of punishment.

“Reformed” prisoners do not conceal that their “re-education” was motivated by a desire for the relative well-being and the small privileges granted to those on good terms with the camp authorities.

Supervisory bodies [10] cover up the cruelties of the regime and the tyranny in the camps, and always support the camp administration. Complaints by prisoners are ineffective, unless such illegalities can be given wider publicity.

The publicity which directs world attention to the evidence of tyranny is, in fact, the corner-stone of the defence of human rights in the USSR. The efforts of the Soviet authorities and certain circles in the West to regard this kind of repression as a domestic, internal Soviet affair are dictated by unworthy considerations of political manoeuvring.

“Please pass our warm greetings to Solzhenitsyn,” says Ivan Svetlichny at the end of the interview, “a man whose courage we all deeply respect.”

The full text of the interview has been published in CCE Archive, No. 1 [11].

♦

[7]

STATEMENTS & LETTERS

The journalists attending the Moscow press conference were also given:

- A statement by prisoners addressed to the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet that refers to the 5 September 1918 resolution, which established concentration camps in socialist Russia (CCE 33.5-2, “In the Perm Camps”, this issue);

- A letter to the Moscow Committee for Human Rights, from Kronid Lyubarsky, Anatoly Goldfeld, Boris Azernikov, Zoryan Popadyuk, Boris Penson and Sergei Babich (CCE 33.4, “In the Mordovian Camps”, this issue): the full text of the letter is reproduced in a samizdat collection, On the Conditions in Which Prisoners are Held, published by Andrei N. Tverdokhlebov [12];

- A statement by Lyubarsky to the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet concerning the release of Silva Zalmanson and Simas Kudirka (CCE 33.8, “Letters and Statements”, this issue);

- The document “A Chronicle of the Gulag Archipelago” (CCE 33.5-1, “In the Perm Camps”, this issue).

♦

[8]

SAKHAROV TO BREZHNEV

A letter from Andrei Sakharov to L. I. Brezhnev (dated 24 October 1974) was read out at the press conference and passed to the journalists.

Sakharov writes:

“The continuation of senseless and cruel repression of human rights and dignity cannot be tolerated on this Earth, even that part of it divided from you by barbed wire and prison walls.

“Brave and honest people cannot be allowed to die.”

The letter contains detailed information about hunger strikes: by Valentyn Moroz, G. Abel, Kronid Lyubarsky and Ivan Gel [Ukr. Hel]; such lengthy collective protests by political prisoners; and mentions hunger strikes by the Baptists Georgy Vins [13] and Boris Zdorovets [14].

These facts “bear irrefutable witness to the acute position regarding political prisoners and their conditions,” maintains Sakharov. He asks for immediate action, so as to avoid a tragic outcome in the hunger strikes at present taking place.

“Political prisoners in the USSR are the victims of ideological intolerance, partly anti-religious in character, of political prejudices, and of the cruel traditions of the system. … A special position amongst political prisoners is held by people who have consciously devoted themselves to the defence of others.”

Among the latter, Sakharov recalls the names of Vladimir Bukovsky, Leonid Plyushch, Semyon Gluzman, Reshat Dzhemilev and Mustafa Dzhemilev, Igor Ogurtsov, and the late Yury Galanskov all of whom have become “symbols of the battle for human rights and against oppression and lawlessness”.

Sakharov‘s letter ends with these words:

“I ask you to consider again the granting of a full amnesty for political prisoners, including those in psychiatric hospitals, the easing of their conditions of imprisonment, and the shortening of the sentences of prisoners in all categories.

“Such decisions would have great humanitarian value, would greatly enhance international confidence and the spirit of detente, and would cleanse our country of the shameful stains of cruelty, intolerance and lawlessness.”

♦

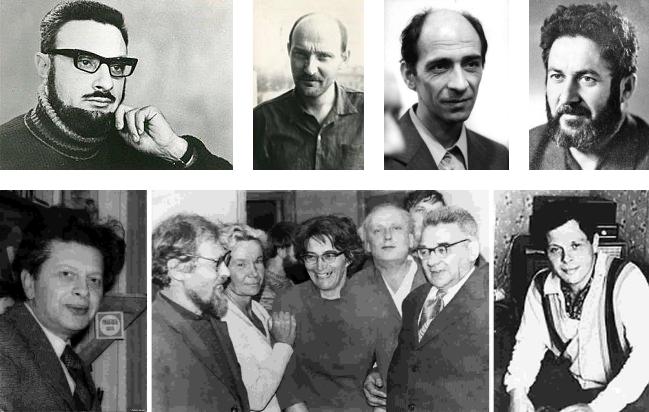

The Action Group for the Defence of Human Rights in the USSR

*

[9]

ACTION GROUP

A statement entitled “30 October” by the Action Group, speaks of the term “political prisoner”. It was signed by Tatyana Velikanova, Sergei Kovalyov, Grigory Podyapolsky and Tatyana Khodorovich.

The statement details (1) the different categories of political prisoners in the USSR; (2) the punishment in Soviet camps in contravention of corrective-labour legislation (but provided for by various regulations and directives) through hunger and cold; and (3) lists the demands put forward on “Political Prisoner’s Day in the USSR”.

The statement adds:

“In giving journalists information about the camps, and, most important, the documents sent out of the camps by the prisoners at enormous risk and with great difficulty, we ask you to remember that the writers are risking the revenge and punitive measures of the authorities.

“Our friends are consciously accepting those risks. It is their wish that these statements and letters be published; it is the duty of those of us who are free to try to protect them from cruel punishment — that is our responsibility, and yours.”

*

The Action Group also gave the journalists a statement about the transfer of Kronid Lyubarsky from a labour camp to Vladimir Prison (CCE 33.4 this issue).

The organizers of the press conference answered a number of questions put to them by the journalists.

With the exception of texts printed in full in this issue or in other publications, the documents mentioned above have all been published in CCE Archive (No 1).

========================================

NOTES

- The death through medical neglect of political prisoner Yury Galanskov two years earlier (CCE 28.2) was one of the many reasons for this protest, in preparation since April 1974. Galanskov died on 2 November 1972.

30 October was the last day of Kronid Lyubarsky‘s trial in 1972 (CCE 28.4).

↩︎ - English translations of the letters mentioned in this report, and many other similar texts were published over the following decade in A Chronicle of Human Rights in the USSR (CHR), Khronika Press: New York (1973-1982).

↩︎ - The Women’s International Democratic Federation (est. 1945) was a Soviet-sponsored organisation with consultative status at the United Nations.

At its suggestion 1975 was declared International Women’s Year and a conference was planned for October in East Berlin. In early 1975 Ukrainian political prisoners in Mordovia announced they would hold a one-day hunger strike on 8 March to secure better conditions for women political prisoners and the immediate release of certain of them (CCE 35.9).

↩︎ - Less than three years after putting his name to this letter Petrov-Agatov signed an article in Literaturnaya gazeta (2 February 1977) that signalled the arrest of Alexander Ginzburg, Yury Orlov (CCE 44.2.2) and other members of the Helsinki Groups across the USSR.

↩︎ - Founded in 1874 as the General Postal Union, incorporated into the United Nations in 1948. Soviet Russia became a member in 1922.

↩︎ - See the later heroic struggle of Mikhail Makarenko to retrieve his missing mail, CCE.45.11 (item 4).

↩︎ - The full text of Lyubarsky’s appeal was published in A Chronicle of Human Rights in the USSR (CHR 1974, No. 12) and in the Nature periodical, London (4 September 1975).

“The World Federation of Scientific Workers” was a Soviet-sponsored organisation (est. 1946) with headquarters in London and Paris.

“The Congress of Cultural Freedom” (est. 1950) was set up to oppose Communist influence in the arts, humanities and natural sciences. Its receipt of funding from the CIA was exposed in 1966. By the mid-1970s it was called the International Association for Cultural Freedom, with headquarters in Paris.

↩︎ - Corrected from the faulty reference (Psalm 90, verse 14) in the Russian original. It should be noted that Psalm 70 in the Western Psalter is Psalm 71 in the Russian Orthodox Psalter.

↩︎ - A wide range of Ukrainian and Jewish prisoners from Ukraine and Russia, with one Russian (Balakhonov) and one Armenian (Shakhverdyan), all convicted under the equivalent of Articles 64-72 of the RSFSR Criminal Code.

↩︎ - Corrective-labour camps and prisons were overseen by a deputy Procurator for the Supervision of Places for the Deprivation of Liberty, i.e., an official from the same body that investigated and prosecuted serious crimes.

Political prisoners (Article 190-1) in camps for criminal offenders, and in separate camps for those convicted of political offences (Articles 64-72), also came informally under the oversight of the KGB.

↩︎ - The full text of the 20-page interview was published in Russian by Khronika Press (New York, 1975) and in an English translation in Survey No. 97 (London, 1975).

↩︎ - This collection is included in the Russian book Andrei Tverdokhlebov: In Defence of Human Rights («Aндрей Твердохлебов – в защиту прав человека»), edited by Valery Chalidze, Khronika Press (New York, 1974).

↩︎ - On Baptist Georgy Vins, see CCE 5.1 item 19; CCE 34.12 & CCE 35.3.

↩︎ - On Baptist Boris Zdorovets, see CCE 7.4 item 5; CCE 29.11 item 8, & CCE 30.14 item 2.

↩︎

======================