SEVEN ENTRIES

[1]

Alexander Solzhenitsyn

August 1914

At the beginning of June 1971 there appeared a report of the publication of August 1914 (YMCA Press, Paris), Solzhenitsyn’s new novel.

The author’s “Afterword“ to the novel specifies the circumstances which prevented it from being printed by Soviet publishing-houses:

“This book cannot now be printed in our homeland except in samizdat, because of objections by the censorship which are unintelligible to normal human reason: even if everything else were acceptable it would be obligatory to write the word ‘God’ with a small initial letter.”

*

[2]

SOCIAL ISSUES, 11

Social Issues, issue No. 11 (May-June 1971).

Compiled by Valery Chalidze.

CONTENTS

Documents of the Committee for Human Rights (CCE 21.5):

- Protocols of 20 May 1971 (on the election of Igor R. Shafarevich to membership of the Committee);

- Roy A. Medvedev: “Compulsory psychiatric hospitalisation for political reasons” (a report to the Committee);

- Alexander S. Volpin: An opinion on R. A. Medvedev’s report;

- Valery N. Chalidze: The rights of persons who have been judged to be mentally ill;

- An opinion of the Committee on the question of the rights of persons who have been judged to be mentally ill;

- A Letter: to the USSR Supreme Soviet’s Legislative Proposals Commission; to B.V. Petrovsky, USSR Minister of Health; and to N.A. Shcholokov, USSR Minister of Internal Affairs (Sakharov, Andrei N. Tverdokhlebov, V. N. Chalidze, and I. R. Shafarevich);

- An appeal by the Committee for Human Rights to the Fifth World Congress of Psychiatrists.

*

[3]

Valery Chalidze

Reflections on Man

This book consists of four sections: “Manifestations of the will”, “Human behaviour”, “Society”, “The ending of bondage”. The author discusses human bio-sociology, ethics and law.

*

[4]

Pyotr Yakir

A Childhood in Prison (part 1)

The author relates what he saw on being arrested in 1937, aged fourteen.

These memoirs cover the years 1937-1944. (Publication begun in Russkaya mysl, Paris, 28 October 1971.)

*

[5]

Smirnovsky

Marxism-Leninism under Lock and Key (Moscow, 1971)

An essay on the artificial creation in the USSR of obstacles to the circulation of the foreign communist press.

Soyuzpechat, the official Soviet distribution agency, sells such publications as Unita, L’Humanite, The Morning Star and so on. The author believes, however, that a number of special measures are taken to restrict their accessibility to the reader. There are delays in the sale of the newspapers, reducing the topicality of the information; “seditious” issues are preserved in the special sections of libraries; the price of the newspapers increases.

*

[6]

G. Svirsky

A letter to V. I. Mishin (lecturer at Gorky University)

In his book Social [Obshchestvennyi] Progress (Gorky, Vyatka publishers, 1970) V. I. Mishin calls for a “national levelling-out” regarding persons with higher education and for the “maintenance of an equal level of development among the peoples [nations, ethnicities] of the USSR”:

“A key role in the question of the development of national relationships in the period of the construction of communism . . . will be played by a further equalisation in the level of development of all the nations and peoples of the USSR”,

since

“there exist in our country not only the remains of an old inequality, but also elements of a new inequality which has arisen during the years of Soviet authority …

“In 1929 the proportion of students among Georgians and Armenians was twice as high as their share of the population of the USSR, while among Jews it was seven times as high.

“The result was a picture of obvious unevenness in the distribution of specialists.”

*

What does he mean, Svirsky [1] asks the author of the book, by the “conscious control of the development of national relationships”?

Drawing on material from the book, he demonstrates that the term “levelling-out” in fact means the barring of Jews from universities and institutes, as was the case in Tsarist Russia when it was motivated by the large proportion of Jews among the revolutionaries. It is common knowledge that during the reign of Alexander III a numerus clausus was established to restrict the admission of Jews to educational institutions: it was set at 3% in Moscow and St. Petersburg; 5% in provincial cities; and 10% within the Jewish Pale of Settlement.

“Judging by your table and by your comments on ‘the new inequality’, you would wish, for example, that the number of Jewish, Georgian and Armenian students did not exceed the ‘proportion in the population of the USSR’ of these nationalities.

“Jews, let us say, comprise 1.1% of the population, and so the quota of Jewish students should not exceed this figure. If we proceed on the basis of this principle, then the quota of Jewish students (which is inevitably introduced by the very term ‘levelling-out’) must be even lower than it was under Alexander. Three to five times lower …”

Svirsky concludes:

“To campaign for this is to campaign for intellectual genocide”.

*

[7]

An Open Letter

to the editorial board of Literaturnaya gazeta.

On 7 June Literaturnaya gazeta published an article by B. Antonov and V. Katin entitled “Wipe away your tears, gentlemen”, which dealt with the trials in Leningrad (CCE 20.1) and Riga (CCE 20.2).

Ten Soviet citizens (Josif Begun, Leonid Makhlis, Alexander Krimgold, Mikhail Alexandrovich, Victor Polsky, David Markish, Esther Lazebnikova-Markish, Mikhail Kalik, Vladimir Zaretsky and Mark Patlakh) accuse the authors of the article of consciously distorting information about the trials:

“We have taken up our pens only because we do not wish to be the passive witnesses of the campaign to misinform the general reader which is being carried out by Literaturnaya gazeta”.

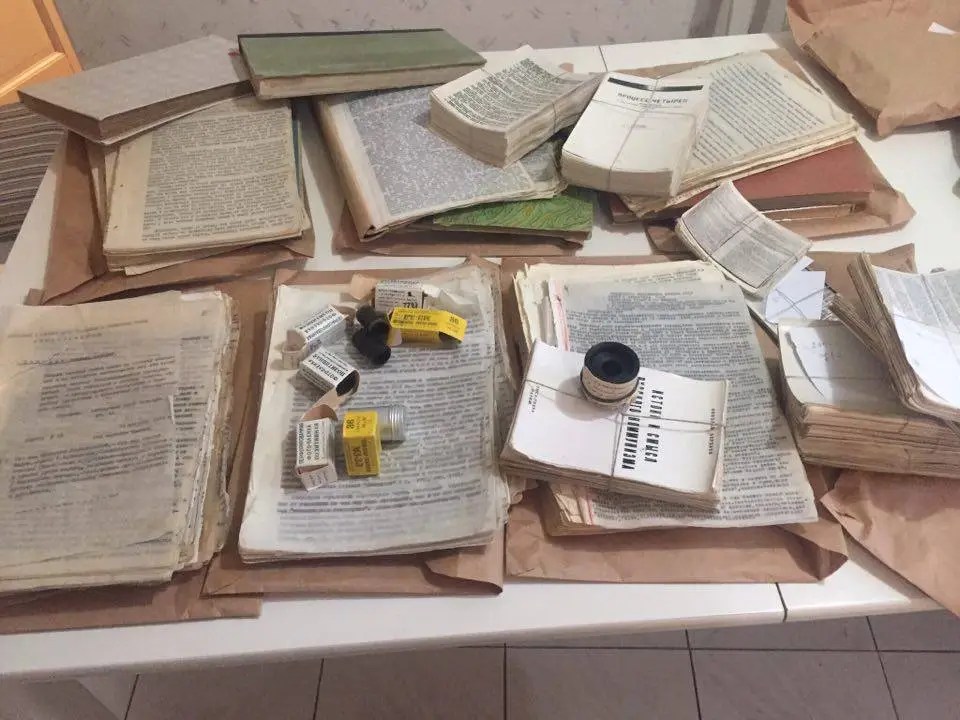

2016 photo, Veronika Lyubarskaya

==============================================

NOTES

- See a speech by the writer Svirsky attacking censorship in A. Brumberg (ed), In Quest of Justice, New York & London, 1970 (Document 61).

↩︎

================================